WHAT did we learn from 2023 about the state of the nation? It was a year that showed how identity can both unite and divide Britain today, depending not only on events at home and abroad, but on how our public conversations are led too.

If Britain needs more bridging voices, King Charles III is keen to volunteer his services. His Coronation, a focal point for 20 million people, sought to delicately blend a thousand years of Christian tradition with the pluralism of a Britain where the most recent census showed every faith to be a minority now. Those are the personal instincts of a multiculturalist King, who senses that this era of political polarisation leaves a gap in the market. This reflects too the enlightened self-interest of a constitutional monarchy, whose legitimacy depends on sustaining much broader public coalitions over a longer timespan than the 45% or 52% that can deliver temporary political dominance.

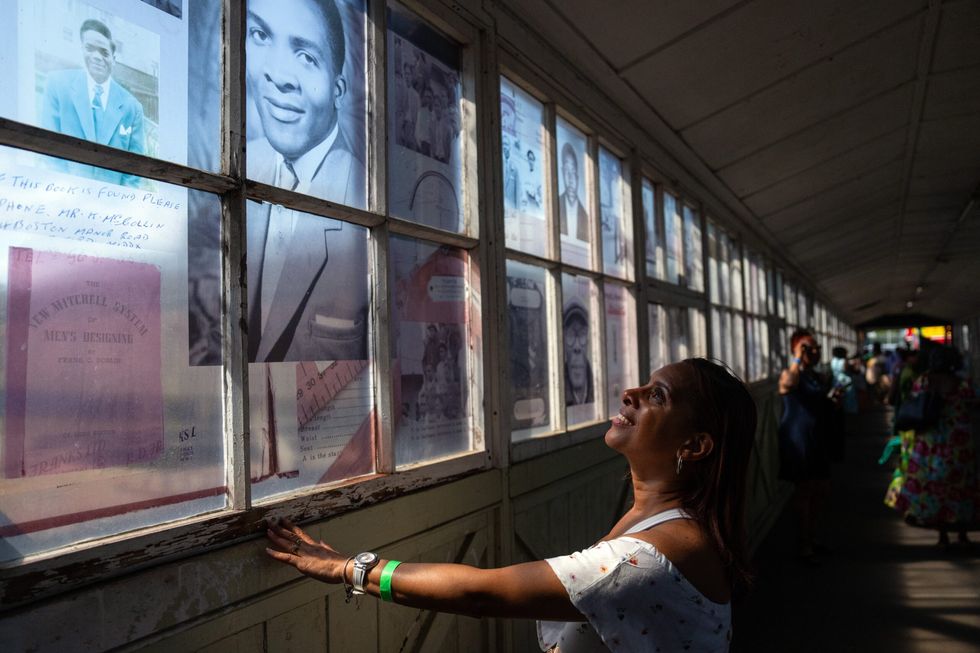

Turning 75 in his Coronation year, the oldest monarch to be crowned, the King linked the 1948 year of his birth to the arrival of the Windrush and the creation of the NHS. This included Charles commissioning ten portraits of Windrush elders for the Royal collection. The Palace was among several institutions to elevate the status of the 75th anniversary of the Windrush – from coins and stamps to celebrations of the contribution to music at the Royal Albert Hall and of the Windrush legacy in football at Wembley stadium.

The many legacies of this anniversary year include plans for Royal Museums Greenwich to create a permanent home for the National Windrush Museum. The Windrush 100 network will also respond to the growing appetite in our classrooms to understand the full story of how post-imperial Britain became the society we share today, building on how the 75th anniversary year showed how conversations about race can rise above so-called culture wars.

2023 arguably counts as a year of political stability, though it rarely felt like it. After all, there had been three times as many Prime Ministers in 2022. Yet Rishi Sunak’s challenge was not mere survival, but how to make this a year of political change for his party. The Prime Minister changed his strategy and public argument several times. His audacious, if unlikely, claim to be the ‘change candidate’ who would break with three decades of Westminster consensus failed to resonate beyond the party conference. The following month, David Cameron was back in the Cabinet.

Sunak chose to end his uneasy coalition with Suella Braverman, whose ferocious response to being fired captured how little trust remained in their working relationship. Yet in response to sacking Braverman, Sunak shifted both his immigration and asylum policies in her direction.

This weekend, the Prime Minister found himself stealing Braverman’s lines about the existential threat of immigration, as he told Georgia Meloni’s semi-reformed post-fascist Italian populist movement that illegal migration had become a “weapon” in the hands of (unnamed) “enemies” which could enable them to “destabilise”, “overwhelm” and “destroy our system of government”.

The high drama of Conservative disunity was a welcome gift for Keir Starmer’s low-drama Labour Party, which anxiously shepherds a broad but potentially fragile ‘time for change’ electoral coalition towards the daunting challenges of office.

The Middle East conflict has seen fierce arguments about war and peace, protest, prejudice and politics at home. Most people want to protect our ability to live together in Britain from the impact of conflict abroad – but are less clear about how to do that in practice. The Together For Humanity campaign has held vigils to grieve the loss of life and voice the mutual empathy of many people who do not feel like taking sides. It may be as important to model how those who do feel a sense of identification or allegiance to Israel or Palestine can be part of the solution too – if they do so in a way that recognises the humanity and interests of both sides. That is not just a foundation for any long-term resolution of the conflict itself, but the key to understanding how we handle differences over events abroad with confidence in our classrooms and universities, workplaces and neighbourhoods.

The flaring up of crises, whether domestic or international, is often a catalyst for belated action on integration. Yet what crises invariably reveal is the quality, presence or absence of our underlying relationships. Ultimately, cohesion cannot just be a matter of crisis response alone. The leadership we need is not just about how we talk about difference – but also about developing more bridging capital and the relationships we need. That is how we could both unlock greater confidence in the everyday experience of living in an increasingly diverse society – and protect our resilience to retain that confidence even when the temperature rises.

His Highness Prince Rahim Aga Khan V

His Highness Prince Rahim Aga Khan V

2023: The year in identity

It was arguably a year of political stability, says the expert