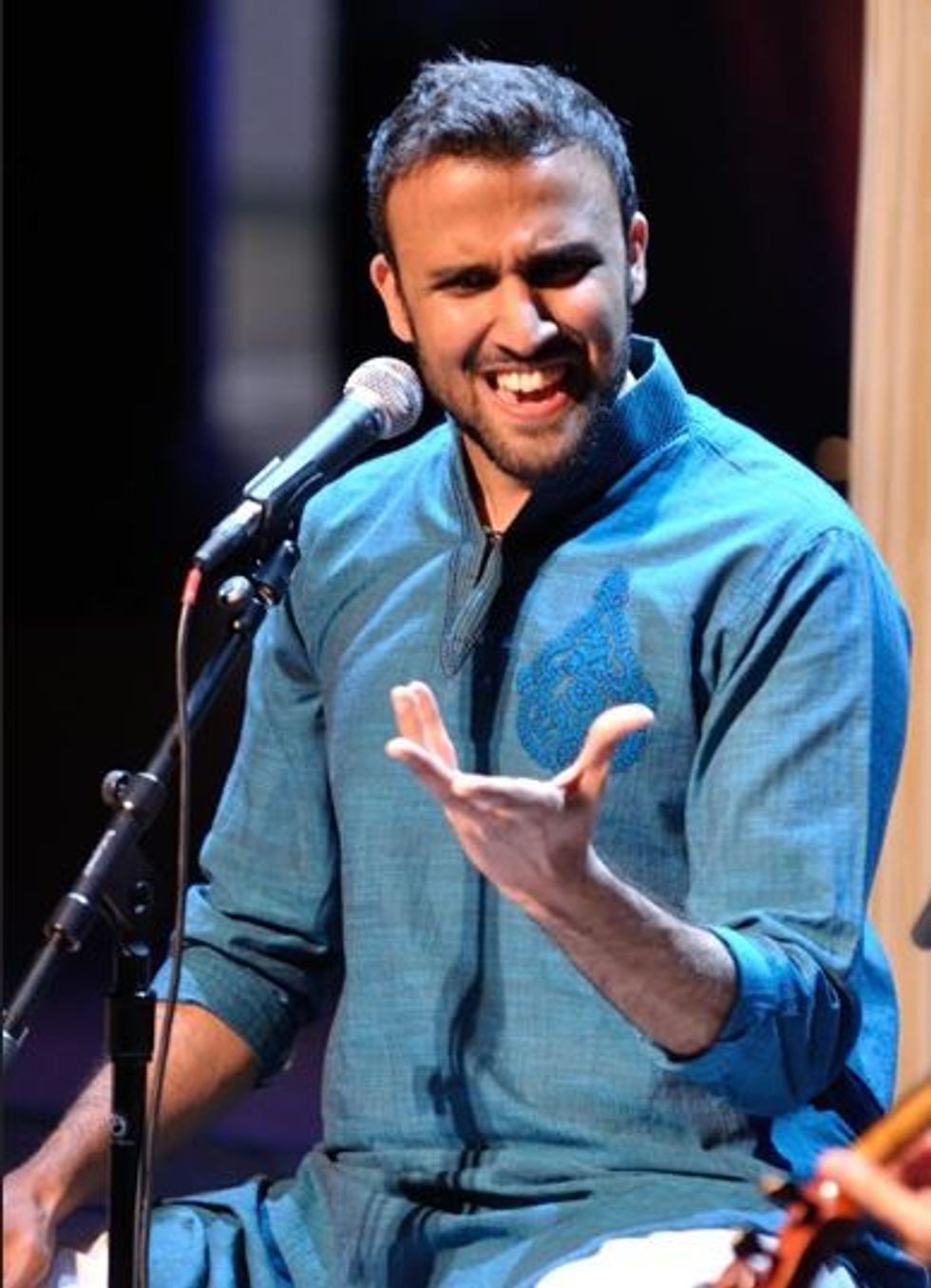

WHETHER it was his first music class as a six-year-old, debut Carnatic music concert at 12, collaborating with world-class artists, releasing music and receiving wide acclaim, Aditya Prakash has had a career filled with memorable moments.

The first great high was touring with music legend Ravi Shankar as a teenager. He has fond memories of the late sitar maestro’s immense humility. “I remember rehearsing at his house; the nervousness before it started, excitement and waiting for him to come into the room. As soon as he came in, his smile and warmth eased all the tension and nervousness. He was someone that really made you feel at ease, despite the age gap, seniority, and respect,” explained Aditya Prakash.

The young talent spoke with great wisdom, maturity, and a clear passion for music. He recalls learning a lot while touring with the Indian classical music icon and recalled: “He would strike up conversations and reminisce about his earlier touring memories. He loved sharing stories with us. The fact that he, being in his eighties, was willing to strike up a conversation with a 16-year-old about music was very special.”

The classically trained singer has since collaborated with big names like sitar queen Anoushka Shankar and world-renowned dancer Akram Khan, along with delivering stunning solo work. This creative path has led him towards his newly released debut solo album Isolashun. The terrific music talent describes the album as a milestone moment in his journey and transformative, in that it’s very different from any other music he has created before.

The starting point for the stunning collection of songs on Isolashun was the Covid-19 pandemic cancelling his engagements and forcing him to stay in one place, feeling unmotivated. Being forced to see the realities within, including social inequalities and division, ignited a spark of musical inspiration. He said: “The political happenings in my two homes – India and the US – made me painfully aware of the one-sidedness of history that we are taught since childhood – in school and in the learning of our Indian ‘classical’ art forms, which are glorified as infallible and divine but built on discrimination and oppression. It made me aware of my apathy – made possible by my privilege – that until now had allowed me to look away from my own complicity in these systems.”

In-depth research and work of his mentor TM Krishna, coupled with the investigation of his own personal and artistic choices made him aware of the tension in his identity. “On one hand, I am a brown artist trying to find accessibility and assimilation in a white world. On the other hand, I am an upper-caste practitioner, claiming ownership of the Carnatic form which is steeped in social hierarchy and caste-discrimination.”

By asking himself multiple questions, including about the aesthetics of sound, its accessibility, fusion, power, and depth, he dug deeper into Indian music to create a unique album. “Isolashun is a self-critique album that explores the tension in dual-identity and questions notions of beauty tied to the ‘classical’ aesthetic. As an artist of a form of music where the aesthetics centre around beauty, divinity and upliftment – how do I explore chaos, tension, division, violence – feelings that are also at the centre of our life today?

“How do I find a connection with my art form that tends to centre around the lofty and the spiritual, while living in a world that is divisive, hypocritical, ugly and messy? How do I find the space between these two, where my music can lie? Isolashun veers towards the experimental side and pushes against the boundaries of genre and form.”

Prakash hopes the album connects with anyone willing to go on the immersive musical journey he has created and also those who are discovering new things within themselves. “I want to connect with anyone who is interested in the search for identity, who asks questions about themselves, about who they are, where they come from, about their own choices and someone who wants to change and evolve, because that is where this album stemmed from personally.”

Being able to generate a lot of emotion in his voice has won Prakash a lot of admiration and it is apparent on the awesome album. While recording vocals for this album he used a lot of dancing techniques learned from his sister Mythili Prakash and Akram Khan, who have been his mentors.

“They don’t act emotion; they feel it and embody that feeling when they’re dancing and choreographing. I tried to use the same technique. So, for a song about boredom or waiting like Maya, which gives a sense of an endless wait, and which we all felt during Covid, I waited until I felt that boredom or listlessness.

“For some songs which were about anger, disappointment or rage, there was enough fodder and fuel around that time in the news that I could easily get to that place. So, it wasn’t about creating an emotion, it was about embodying an emotion and letting that flow through me when I sang, performed, or produced the music. So rather than portraying an emotion, it’s about embodying an emotion, and that makes it easier because it’s more honest. You’re not acting, you’re being.”

Looking ahead, Prakash has no plan and wants to have the ability to create music from an honest place, while still being inspired by everything around him. These inspirations include nature, the news, interactions with friends,loved ones, and conversations with artists he admires. “But what inspires me the most is witnessing and being part of the creative process of another artist.

“For me that’s been my sister Mythili Prakash, Akram Khan, TM Krishna and Vincenzo Lamagna; all of whom have been mentors on this album. And watching how they create inspires my own process as well.”

Prakash has a profound reason for people to pick up his new album and who he wants it to connect with: “In today’s technology age, endless choice and doom-scrolling, someone who just wants to be in the moment, centred and immersed in something as simple as just listening to music. Right now, listening to music is on in the background while we do other things like cooking, studying, or writing a paper. But what has happened to just sitting and listening to the music itself?”

“I think there is a lot of move[1]ment towards more simplicity, being more mindful and doing one thing at a time. This album is meant to be that – to be an anchor in a space of immersion, so if one is willing to do that. If one wants to go to an immersive space, then I think it’s worth picking up this album and giving it a shot.”