By Rithika Siddhartha

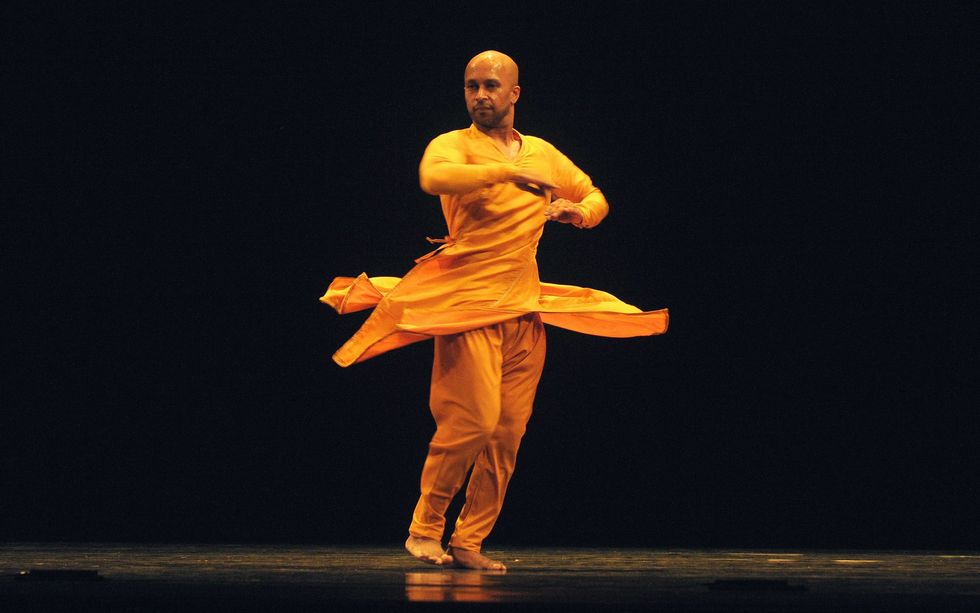

ACCLAIMED dancer Akram Khan has revealed his sadness that Asians shun his work as he prepares to perform his solo, Xenos, about soldiers from the subcontinent who fought for the British Army in the First World War.

Khan also said it was only as recently as 2018 when he first learned about the role of Asian troops in the two world wars.

“It was not told to me,” Khan told Eastern Eye in an interview last month, explaining he did not learn about the role of black and Asian soldiers while in school. He became aware of it only in the run-up to the centenary of the first world war a few years ago.

Khan's company is presenting three shows this season as part of the Carnival of Shadows at London’s Sadler’s Wells.

He recalled how articles published in the run-up to the (First World War) centenary a few years ago caught his attention.

“Between 2014 and 2018, was the celebration. I don't know why we call it a celebration. That’s a bit bizarre for me. But, it was, perhaps to remember, let's put it that way.

“What are we remembering? For me, it was not a remembrance; it was discovery, because articles were coming out by people of colour, who had done their homework. That's when we discovered about colonial soldiers who fought for Britain.”

Khan added, “I feel sad that there's not enough Indian, or people of colour, who come to see my work.

"It is really extraordinary. It's about Indian soldiers, you have some (from the) young generation. But that's the joke of it all - that you don't have Indian communities (watching Khan’s performances).

“The majority (of the audience) is white, I have to say, but there is a mix of different cultures, different people of colour that do come, but it's usually the young generation - it's interesting; not my parents’ generation – yet, it’s the story of my parents’ generation and their grandparents.”

Khan grew up in south London with his parents who ran a curry house in Wimbledon and recalled how he was was angry "for a long time" when he was younger.

“Because I was not accepted within the Asian community.

“It was the Caucasian people who embraced me.”

Khan won an Olivier Award in 2019 for Xenos and returns to perform the solo from November 30 to December 4. It will be followed by Chotto Xenos, which is inspired by Xenos, but is aimed at children.

These two productions - along with the ongoing Outwitting the Devil - complete the Carnival of Shadows.

“It was inspired by what’s happening in the world today, but I always want to usually connect it with a myth that I can use as a kind of a groundwork, from which to then plant the present situation,” Khan said.

“It's about giving (voice to) the ones in the shadows and putting them in the forefront and saying, ‘we are here to listen. Let me be the body, or bodies, that tell your story.”

In a wide-ranging interview, Khan spoke about bias in all cultures, why people have forgotten to listen, the stories he's drawn to, how the younger generation of dancers is different to him and why diversity is a word created by white people.

'Not pandering to an imperial lens'

Born to immigrant, working class parents, Khan has previously spoken about how he endured racist behaviour while working in his father’s restaurant. By his own admission, he was not cut out for a career in engineering, law or medicine - the holy grail for most immigrant parents. Instead, his interest was in pursuing dance, so his mother took him to learn kathak, the Indian classical dance form with its distinctive footwork, at the Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan in Kensington, west London.

An enthusiastic and eager student, Khan remembers wearing out the kitchen floor’s linoleum multiple times as he practised kathak at home.

Today, he runs a successful dance company, with acclaimed and varied productions – from Desh to Giselle, with the English National Ballet, and multiple collaborations, including Sylvie Guillem, Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui and Israel Galván.

Khan told Eastern Eye, “I was very clear from the beginning - I don't want to make work that caters to their (Caucasian) perspective or their imperial lens.

“Perhaps that's why I get a lot of - some of the reason, not all - sometimes I get real tension from critics and people. Because I'm not pampering (them) by making work that is colonial, in some way.

“I want to make work because I believe in it, and it's rooted deeply in me. And I've always tried to stick to that, really. And some people embrace it, and some people will not.

“I want to move people with my work; I want to try and make work that belongs to everyone. That everyone can relate to, without compromising my craft.”

Outwitting the Devil, the first production under the Carnival of Shadows, was proposed to Khan by Ruth Little, his dramaturg. Its theme is drawn from one of the oldest myths known to humankind, the story of Gilgamesh, Khan said.

“In the most simplistic way, Gilgamesh represents the majority of the politicians we have experienced today, the very patriarchal dictators, power hungry, (with their) sense of controlling the mass, not giving voice to the mass.

“But what's specific about Gilgamesh in this particular narrative is the relationship to nature.”

Khan’s interest in the story was sparked by a conversation with his young daughter when she was about six (she’s now eight).

“We were talking about climate change and how the world is changing. The story of Gilgamesh is about his relationship to nature. His view is that we own the earth, we own everything; that mankind - not humankind - owns the earth, owns nature.

“What's interesting is that even though Gilgamesh is from a patriarchal system, it is the exact opposite for nature, which is very maternal - it nourishes, it feeds, it guides.

“There's something sacred and spiritual about that, about nature and earth. So, the story, even though it's been taken from Gilgamesh, it's really about what we're experiencing today. Our relationship to nature and how disconnected we are.

“Gilgamesh's story is a lesson for us to learn from, because what happens is Gilgamesh destroys a part of nature. And then nature takes revenge, the gods take their revenge, and take away Gilgamesh’s most loved possession.

“In a sense, now looking at the world we're living in, can you imagine an invisible virus has brought humankind to its knees?”

The artist explained the consequences of not heeding nature, pointing to “our sense of denial, of amnesia or dementia - we have global dementia. We're almost acting like nothing's happened. And we're going back to some sort of normality, rather than going, ‘what can we learn from this? What is nature telling us?’

“We don't relate to nature in that way. We don't have a conversation with nature. We don't listen (to nature), we stopped, we've lost the art of listening. And I think that's common in all three of my productions.”

Khan speaks with passion about the interpretation of religion, the importance of storytelling by people of colour, contemporary politics and the widespread prevalence of bias.

“There's so many of us deniers, even in my own culture. It's not a pandemic of just white people,” he said, referring to how Covid-19 has had a disproportionate impact on black, Asian and ethnic minority communities.

“There's racism, there's inherent biases in all cultures. So it's whether we choose to acknowledge it. It's the listener who has dementia, chosen dementia, they choose to have dementia.

“Too often, the stories I had studied, and my generation and the generation before me, predominantly, in the West, (the stories) were mostly from a white, male perspective. How do we shift that? Carnival of Shadows celebrates the voices that were not heard.”

'Not enough artists are speaking up'

Dance, he said, while it was embraced in many cultures, is undervalued as an art form.

“It's not easy. Because science and technology and other subjects are always at the forefront, at the top of the list; there is hierarchy. Art seems to be a kind of almost regarded as an entertainment - it is entertainment, too. But it's also a lesson, it's a life lesson.

“For me, the most important science is in your body. And we still don't understand our body. We still don't understand the mind. I think it can be given more reverence, more respect.”

However, Khan added, “It's not the role of the artists to be able to change political policies. We can't do that. We can collectively, maybe, fight for it. But not enough of us are fighting or speaking up.

“That's worrying and the funny thing is, we live on one earth, there is no moon. It doesn't matter what (Jeff) Bezos (of Amazon) says; it doesn't matter what none of those men say. We live on one planet. In the end, this is our home. And the earth will continue without us. We seem to be the cancer.

“I feel nobody's listening to (young climate change activist) Greta Thunberg. Especially the people in power. Yet she's the only one fighting for the truth with the young generation, for their future. And it should not be held to ransom by any person in power.”

The appeal of myths

Now in his 40s, Khan has produced a body of work that has explored stories from mythology as well as real life, but said he has been drawn more to the former genre.

“I've always been connected to mythology. I find it very exciting. And I feel very much more connected than present-day stories.”

He described how he chooses what tale to tell.

“First, what's important is whose lens are we hearing the story from? That's completely crucial. Before the stories themselves, I ask, ‘whose lens are we experiencing this narrative from? Is it the victors? Or is it the victims?

“What appeals to me usually are stories that are unheard of, untold — if I feel there is a deep sense of learning from that narrative. That's the purpose of a myth, of all stories that became religious.

“It's not about you being literal, don't take it literally. It's a metaphor. It's there to learn from, to not make those mistakes. That's what it's there for. So many of us misunderstand religion and assume that it's telling you exactly what to do. No. It's much deeper than that. It's not a practice. It's a belief. Belief is something that is like air. It's water. It's alive. It's not in the book.”

Khan added that “we're in a bit of a myth gap”.

“It's hard to know what the myth is today. What is it to be human? That's something I'm looking for. And I think it's harder for me in my position. It's harder now than it was before. Because I'm kind of going a little bit to the threshold of being a little bit bolder, by putting a mirror up to society.”

In a recent previous interview, Khan pointed out the lack of diversity in the boardrooms of arts organisations. He told Eastern Eye, “Who are the gatekeepers? That's what I want to say. That's the first thing you look at. And I have to be careful of diversity because that's (a word) made by white people. It's a colonial word, an imperial word that's been designed for them to feel accepted, that they're accepting of others. So, yes, the board has to have people of colour or if they're the gatekeepers.”

Khan also confessed to not being able to execute some of his dance moves easily, as he gets older.

He said, “Oh, I have to sweeten it a lot. I have to negotiate with it. I have to massage it. It's such a diva, my body now. It says, ‘No, I don't want to do this movement, that movement, nope, this is too much’. It’s constantly complaining.

“It used to be silent before 30. It's because you choose not to listen to it or give it voice. There's no negotiation. It's a bit like the problem with Gilgamesh. You feel you own your body. So you can abuse it the way you want. The body is part of nature, too. It's an energy, right? It's a life force. And our bodies are also living museums. I love museums - don't get me wrong - but they're manmade. And the arrogance of our modern civilization that thinks we can put things, we can put an experience into a museum. Our own bodies are living museums.”

'Will there be another Akram Khan?'

Asked if he sees another Akram Khan among the younger generation of dances, he said, “I really hope not.

“There's a lot of talent that will not be another Akram Khan, but that will be its own entity. The young generation has this huge amount of talent. But our goal is different. With the new generation, there is a real sense of wanting to get it very quickly. And what is that thing you want to get? What is success?

“I loved dancing. I love telling stories through my body. You put me on a street, I'll do it on a street. If you don't want to pay me, that was okay. That's how I was when I was younger. I just wanted to learn. I wanted to dance. And I just needed a space to dance.

“It's so different now. It's about social media, how do I get my name seen? I think if your work speaks, even in the corner of an alleyway, and there are a few witnesses, that word will spread.

“Of course, there's luck. The right people, at the right time, might see you and put you on a mainstage. But what's really interesting with technology is it can spread like wildfire - if there's something special happening.

“There's so much talent, but nobody has the patience to listen anymore, to knowledge. We want to listen to information. And information is just data. We're more impressed by data.

“Knowledge is data that has been embodied, that has been experienced. It's an experiential information. We don't listen to our grandparents’ stories. We're too concerned with the future. . If you want to know how to move forward, you have to look at your past. One is connected to the other, the past is not behind you, it is in front of you. Because you can see it, you can see everything that's happened. The future is behind you, because you cannot see it.”

www.sadlerswells.com/akram-khan-company-carnival-of-shadows/

Michael Gove

Michael Gove Jeremy Hunt

Jeremy Hunt