CONSERVATIVE voters have slightly larger amygdalas, or fear processing centres, compared to progressive ones, according to a new study.

Researchers from the Netherlands, which is known to have a multi-party system, replicated a 2011 study of 90 university students in the UK.

Looking at MRI brain scans of 928 individuals aged 19-26 years, the researchers found the link between one’s amygdala size and conservatism also depended on the political party that the participant identified with.

“The amygdala controls the perception and the understanding of threats and risk uncertainty, so it makes a lot of sense that individuals who are more sensitive towards these issues have higher needs for security, which is something that typically aligns with more conservative ideas in politics,” first author Diamantis Petropoulos Petalas, from the University of Amsterdam, said.

The findings, published in the journal iScience, were in line with those from the earlier UK study, the researchers said.

“The Netherlands has a multiparty system, with different parties representing a spectrum of ideologies, and we find a very nice positive correlation between the parties’ political ideology and the amygdala size of that person,” Petropoulos Petalas said. “That speaks to the idea that we’re not talking about a dichotomous representation of ideology in the brain, such as Republicans versus Democrats as in the US, but we see a more fine-grained spectrum of how political ideology can be reflected in the brain’s anatomy,” Petropoulos Petalas said.

Researchers said those who identified with the Dutch socialist party – considered to have radically left-wing economic policies, but more conservative social values – had on average more grey matter in the amygdala, compared to the participants who identified with other progressive parties.

They explained that because the Netherlands has a multi-party political system, the team was also able to compare brain structures along the continuum from left- to right-wing, in contrast to the two-party system in the UK.

A participant’s ideology, including political identity and stance on socioeconomic issues, was analysed by their responses to a questionnaire. The responses revealed varied aspects such as the political parties that the participant identified with and how they stood on women’s and LGBTQ rights.

However, in contrast to the UK study, the authors did not find any link between conservatism and a smaller volume of grey matter in the anterior cingulate cortex, a brain region that manages impulses and emotions.

Depending on a person’s economic and social ideology, both the amygdala and anterior cingulate cortex physically differed, indicating that relationships between political ideology and brain structure are nuanced and multidimensional, they added.

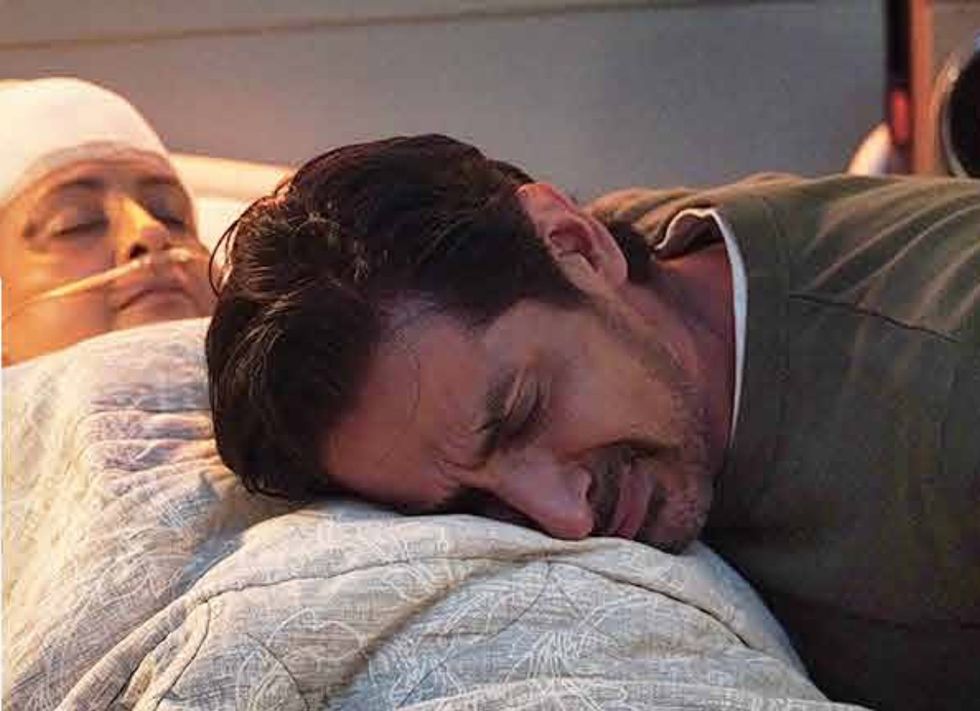

Mitul Patel’s ‘Mercy’ sparks global debate on love, loss, and morality. Screening now at UK Asian Film Festival

Mitul Patel’s ‘Mercy’ sparks global debate on love, loss, and morality. Screening now at UK Asian Film Festival

From Starstruck to The Devil’s Hour, Nikesh Patel proves versatility is his superpower

From Starstruck to The Devil’s Hour, Nikesh Patel proves versatility is his superpower Nikesh Patel owns the spotlight in Speed as the bold new voice in British storytelling

Nikesh Patel owns the spotlight in Speed as the bold new voice in British storytelling Nikesh Patel with Rose Matafeo in Starstruck

Nikesh Patel with Rose Matafeo in Starstruck