SINCE I happened to be passing through Udaipur [in Rajasthan], I thought I would look up “Shriji” Arvind Singh Mewar.

He didn’t formally have a title since Indira Gandhi, as prime minister, abolished India’s princely order in 1971 by an amendment to the constitution. But everyone – and especially his former subjects – knew his family ruled Udaipur, one of the erstwhile premier kingdoms of Rajasthan.

At independence in 1947, some 565 princely states joined the Indian union. As an inducement, the rulers were promised they would be allowed to keep their titles and given an annual privy purse.

His Highness Arvind Singh Mewar preferred to be called by an affectionate term of respect – “Shriji”.

I see from my notes that he attended two events organised by the Indian Journalists’ Association (IJA) in the UK.

On June 21, 2013, he was present at a lunch at Lord’s, where the IJA launched a book, Pataudi: Nawab of Cricket. Shriji did the formal honours at the event, with guests including Pataudi’s wife Sharmila Tagore, and their children – daughters Soha and Saba as well as actor Saif Ali Khan – and his wife Kareena Kapoor Khan.

A month later, the IJA hosted a lunch for Shriji at Carluccio’s, behind Oxford Street, where he talked about water being a scarce resource in an arid state like Rajasthan.

Far from behaving like a Maharana – the title signifies he was one step up from being a Maharajah – he went round the table, greeting each journalist and gifting them a copy of a book he had written about the House of Mewar, which claims descent from the Sun God.

On one occasion, someone asked him what he thought about the British royal family.

“Very good family,” he quipped, “but a bit new.”

He regarded himself as a “custodian”, rather than a ruler. He was 76th in a dynasty whose origins date to AD 566 (in contrast, the House of Windsor came into being in 1917, replacing the historic Germanic name of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha).

Like many erstwhile rulers, Shriji went into running hotels, in his case in partnership with the Taj Group. The Lake Palace, which is probably the most magical hotel in the world, is one of his properties.

On a previous trip, he had invited me to go round for drinks in a corner of the City Palace he occupied with his family. He didn’t like to say, “Come to my palace.” Instead he said, “Come to my place.”

When I casually mentioned to a friend I was thinking of sending him a message this time, he showed me on the internet on his mobile that Arvind Singh Mewar had died on March 16 at the age of 80.

This was very upsetting.

The following morning, high up in the Aravalli Hills above Udaipur, I spoke to some locals about their beloved Maharana.

“All the development you see around Udaipur was because of him,” remarked one man with a sweep of his hand.

There was a huge turnout out for Shriji’s funeral.

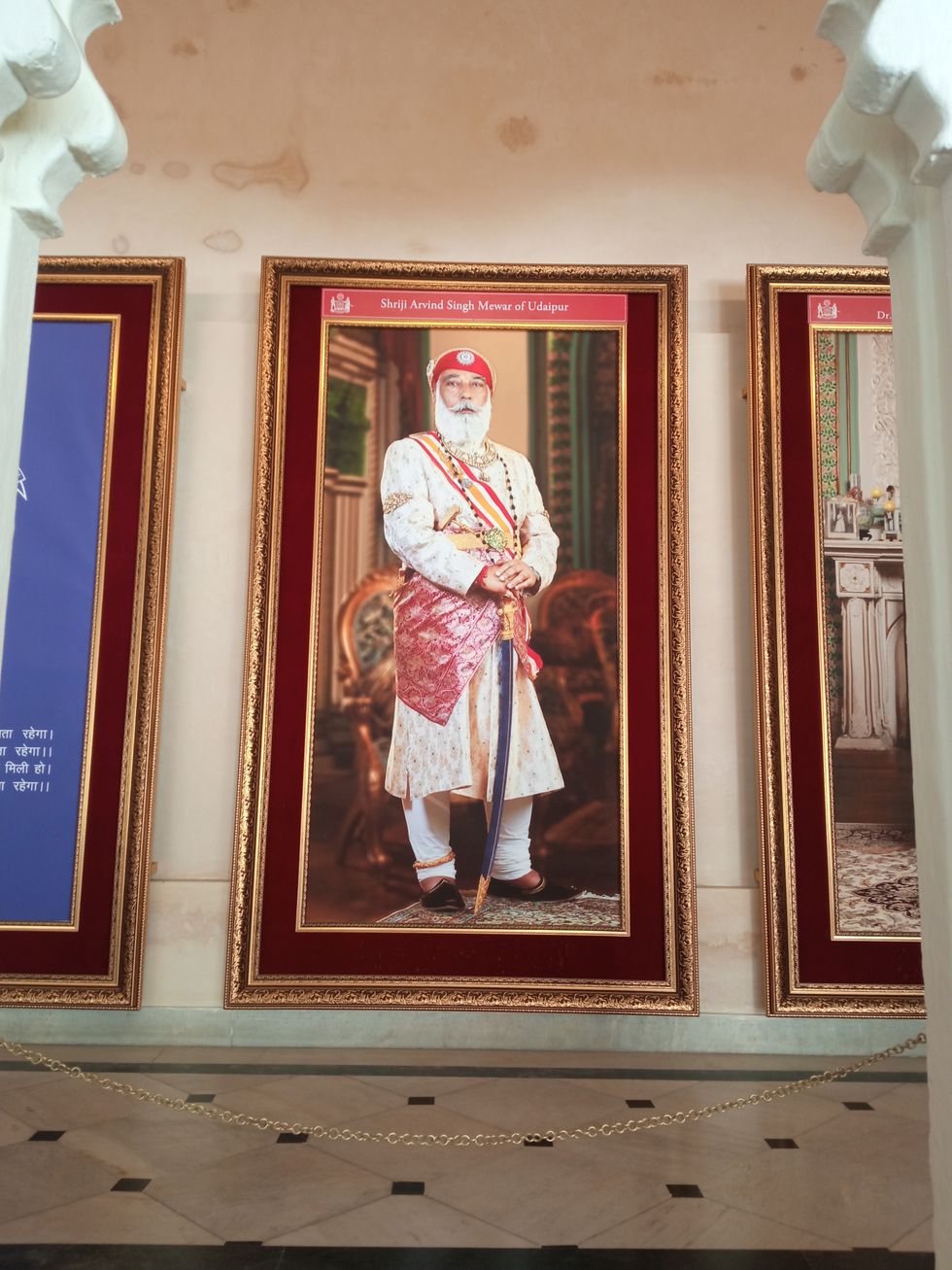

As I went round the City Palace, I took note of Shriji’s portraits and those of his ancestors.

Preparations were already under way for the coronation of his son, Lakshyaraj Singh Mewar.

Although Mrs Gandhi scrapped the old princely order, considering it to be an anachronism in modern India, Air India is bringing back its Maharajah service.

When I routinely flew Air India from Heathrow to India as an undergraduate – those were the days of the legendary Maneck Dalal – the airline’s famous symbol was a bowing Maharajah.

That is considered too subservient for today’s India, I have been told, but the nation’s flag carrier aims to return Air India to the glory days of old.

Pakistani artist Moazzam Ali Khan caught the attention of Bollywood legend Javed Akhtar with his soulful YouTube cover of Yeh Nain Deray Deray

Pakistani artist Moazzam Ali Khan caught the attention of Bollywood legend Javed Akhtar with his soulful YouTube cover of Yeh Nain Deray Deray John Abraham to headline action thriller Tehran

Getty Images for DIFF

John Abraham to headline action thriller Tehran

Getty Images for DIFF

Tikri Border, Haryana-Delhi by Aban Raza

Tikri Border, Haryana-Delhi by Aban Raza Harmz Matharu

Harmz Matharu Abhishek Bachchan in Be Happy

Abhishek Bachchan in Be Happy Devika's soulful vocals shine in her new Punjabi ballad Wisteria

Devika's soulful vocals shine in her new Punjabi ballad Wisteria Indian Idol star Nitin Kumar promises a soulful mix of qawwali, Sufi, and folk music at his upcoming UK performance

Indian Idol star Nitin Kumar promises a soulful mix of qawwali, Sufi, and folk music at his upcoming UK performance Kunal Kamra during his show

Wikipedia

Kunal Kamra during his show

Wikipedia

Swiss-Indian singer BombayMami is making waves with her bold style and sound

Swiss-Indian singer BombayMami is making waves with her bold style and sound Hania Aamir receives a questionable honour in London

Hania Aamir receives a questionable honour in London

A resident in Odessa, Ukraine, as smoke rises from a fire following a strike earlier this month amid the Russian invasion

A resident in Odessa, Ukraine, as smoke rises from a fire following a strike earlier this month amid the Russian invasion

Shweta Warrier

Shweta Warrier Harbans Singh Jandu

Harbans Singh Jandu Aamir Khan

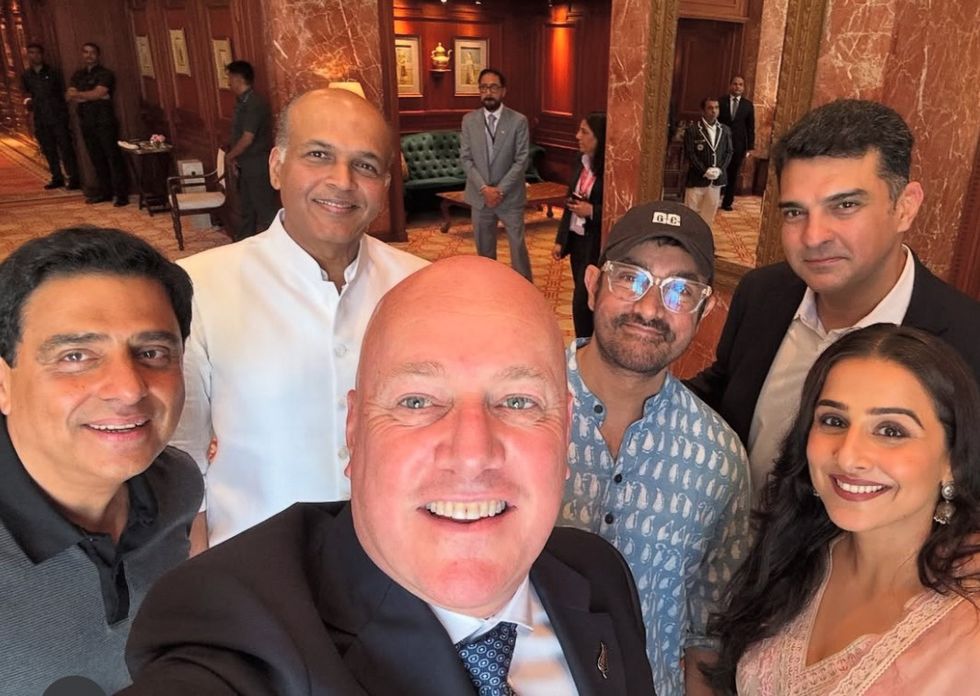

Aamir Khan Ronnie Screwvala, Ashutosh Gowariker, Christopher Luxon, Aamir Khan, Siddharth Roy Kapur and Vidya Balan

Ronnie Screwvala, Ashutosh Gowariker, Christopher Luxon, Aamir Khan, Siddharth Roy Kapur and Vidya Balan Madhuri Dixit

Madhuri Dixit

Anurag Bajpayee's Gradiant: The water company tackling a global crisis