THE world watches America anxiously. Kamala Harris versus Donald Trump does not seem so difficult a choice for many beyond America.

The British public would put Harris into the White House in a cross-party landslide – with only Nigel Farage’s Reform voters breaking for Trump. But it is not up to us. The handful of voters still undecided in Pennsylvania and the other swing states will make a choice that will reverberate beyond America.

Polarisation can mobilise. This will be the first general election year of modern times when US turnout is higher than that in Britain. America’s turnout hit a record two-thirds of adults in 2020. In Britain in 2024, only half of eligible adults both registered and voted – and not only because our election outcome seemed obvious.

This tale of two elections illustrates contrasting challenges for the health of democracy.

The question for British democracy is whether the political stakes seem too low. Chancellor Rachel Reeves’ budget challenge this week was not only how to make the tax and spending numbers add up, but to start to persuade a sceptical public that elected governments can still make a useful difference to their lives.

America’s election dramatises the opposite challenge – of what can happen when the political stakes feel too high. The words ‘culture war’ are often thrown around like confetti during any identity twitterstorm. The 2024 US election meets the threshold to use the phrase seriously – as a proxy war without (one hopes) the shooting. The sense of existential threat comes from clashes over fundamental principles that it is hard to agree to disagree about – including issues from abortion to immigration, and racist language used to threaten mass deportations as the only way to prevent America being destroyed by an ‘invasion’ of migrants.

Khudadad Khan (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)Three quarters of Americans – a majority on both sides – doubt that former president Trump would acknowledge a defeat at the ballot box, though three-quarters do believe that Harris would concede if she lost.

The US, which is split deeply in two, seems to have lost something it once seemed good at – recognising that making an increasingly diverse society work depends on both respecting difference and working together on what can be shared.

America’s polarised election clash coincides too with Britain’s annual rituals of Remembrance. The armies that fought in the world wars resemble more closely Britain of 2024 than that of 1914 or 1944, in their ethnic mix and faith diversity. It should be a message with increasing relevance this year following a summer scarred by racist riots and the fear that they spread across the country.

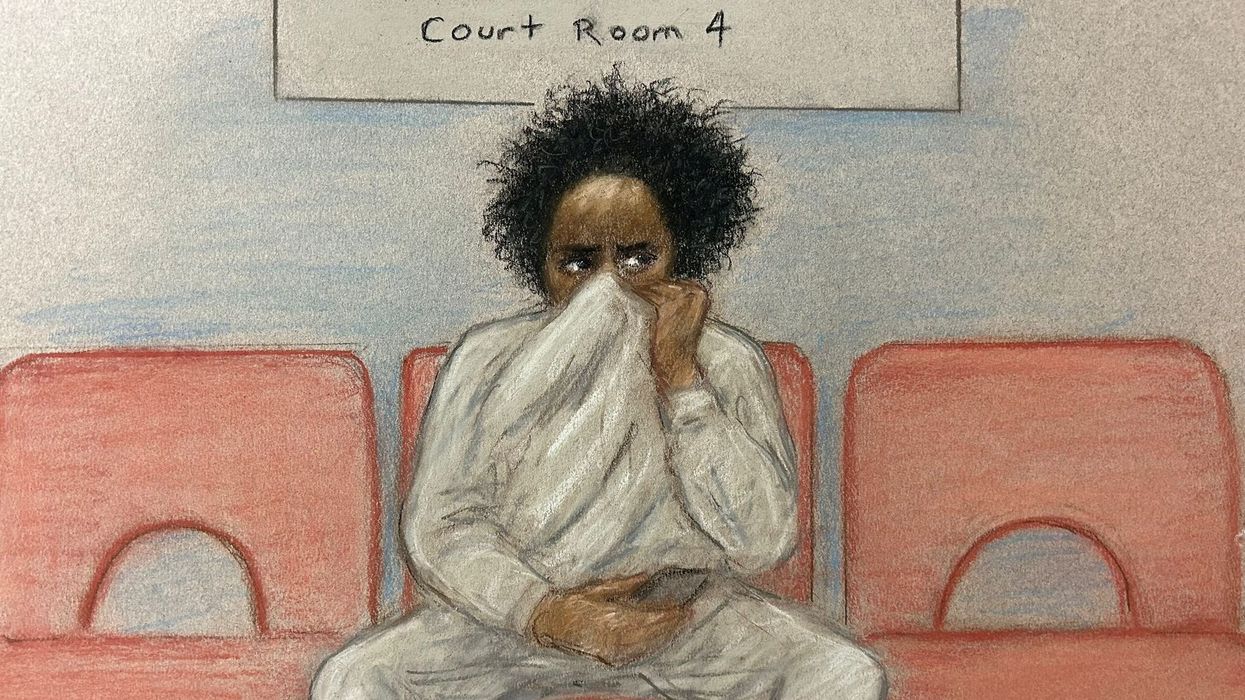

It is 110 years ago this week that Sepoy Khudadad Khan of the 129th Baluchi Regiment, wounded and outnumbered, survived a battle in Ypres. He was presented with the Victoria Cross medal by King George V himself the following year while recovering in England from his injuries. He was the first Indian Army solider and Muslim soldier to receive the honour.

The four million Indian Army soldiers who fought in two world wars were seldom recognised until the 1990s. It was the First World War centenary commemorations, a decade ago, which made this majority knowledge for the first time.

There were many creative efforts to project this story of service and sacrifice to those who had not heard it before. Lord (Jitesh) Gadhia’s idea of a Khadi poppy was sported not just by prime minister Theresa May in the Commons, but also by Virat Kohli and Joe Root as they captained India and England, respectively.

A young Muslim fashion designer worked with the Islamic Society of Britain to produce a poppy headscarf to mark the centenary of Khudadad Khan’s Victoria Cross.

Even the actor Laurence Fox’s clumsy Question Time objection to the “oddness” of seeing a Sikh solider in the film 1917 became an opportunity to educate the public on the Sikh contribution to the war effort.

Yet, important gaps remain. Two thirds of the public are now aware that Indians served – but only half as many realise that many were Muslims from modern-day Pakistan.

Sunder KatwalaOnly a third know of the contribution of forces from the Caribbean – when the journey from war to Windrush provides the foundational moment in post-war immigration that shaped modern Britain. Over a third of those on board the Windrush had served in the RAF.

This government’s curriculum review should consider how to join those dots so that each generation can understand how today’s multi-ethnic classrooms came about.

And next spring’s VE Day celebrations could also be used creatively to help decisively push each of those contributions towards becoming majority public knowledge too.

Wearing poppies and falling silent in memory of service and sacrifice has been a cherished tradition in this country for a century.

Yet we have not yet fully untapped its potential to broaden confidence in how an increasingly diverse Britain can strengthen our sense of a shared past, present and future too.

(The author is the director of thinktank British Future)

Britney Spears and Sam Asghari at the premiere of 'Once Upon a Time...In Hollywood' in 2019Getty Images

Britney Spears and Sam Asghari at the premiere of 'Once Upon a Time...In Hollywood' in 2019Getty Images

The much-loved duo Vijay Deverakonda and Rashmika Mandanna in the Geetha Govindam posterInstagram/Geetha Govindam

The much-loved duo Vijay Deverakonda and Rashmika Mandanna in the Geetha Govindam posterInstagram/Geetha Govindam A glimpse of Vijay Deverakonda and Rashmika Mandanna's chemistry in Geetha Govindam Instagram/Geetha Govindam

A glimpse of Vijay Deverakonda and Rashmika Mandanna's chemistry in Geetha Govindam Instagram/Geetha Govindam