By Amit Roy

INDIAN soldiers who gave their lives for Britain in the First World War were often buried in unmarked mass graves in Mesopotamia and in Africa, a report published last week by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission has revealed.

An inquiry was set up in December 2019 to review “historical inequalities in commemoration” following a TV documentary by the Labour MP David Lammy.

Research on the history of the Imperial War Graves Commission – it was renamed the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) in 1960 – found that while memorials in war cemeteries invariably had the names of white British soldiers inscribed in stone on them, frequently only the number of Indians who had died in battle was mentioned.

While it is believed that most of the names of the Indian soldiers exist somewhere in army records – these are now being added to memorials – the situation involving African soldiers and labourers is very different. The names of between 116,000 and 350,000 Africans may have been lost for ever.

It appears that in the highest reaches of the armed forces and the colonial administration, there was a view that the same standards did not always have to be extended to Indian and African soldiers.

The report says: “The Imperial War Graves Commission (IWGC) was founded in 1917 to commemorate in perpetuity the men and women of the British Empire who lost their lives in the First World War.

“It would extend its charter to incorporate just one other conflict, the Second World War, and now – more than a century since it was established – it preserves the memory of more than 1.7 million Commonwealth citizens who died in those struggles. It does this by maintaining cemeteries and memorials at more than 23,000 sites across the globe.”

The report says “the Indian Army alone provided more than 1.2 million men, with its soldiers deployed to all the main theatres of the war, and making up two-thirds of all the manpower serving in Mesopotamia”.

Mesopotamia occupies the area of present-day Iraq and Kuwait, and parts of Iran, Syria, and Turkey.

This report finds that “in the 1920s, across Africa, the Middle East and India, imperial ideology influenced the operations of the IWGC in a way that it did not in Europe, and the rules and principles that were sacred there were not always upheld elsewhere.

“As a result, contemporary attitudes towards non-European faiths and differing funerary rites, and an individual’s or group’s perceived ‘state of civilisation’, influenced their commemorative treatment in death.”

One principle established right at the outset was that the fallen would not be repatriated to Britain since it was felt only the rich would be able to do so. Rudyard Kipling, who wrote a poem, My Boy Jack, lamenting the loss of his own son, became literary adviser to the IWGC. His description of those buried without being identified was, ‘Known unto God’.

In 1919, he noted that “... the treatment of the bodies of … (Indian) soldiers will be in strict conformity with the practice of their religions”.

The report states: “In conflict with the organisation’s founding principles, it is estimated that between 45,000 and 54,000 casualties (predominantly Indian, East African, West African, Egyptian and Somali personnel) were commemorated unequally.

“For some, rather than marking their graves individually, as the IWGC would have done in Europe, these men were commemorated collectively on memorials. For others who were missing, their names were recorded in registers rather than in stone.”

‘Two-tier system for Indians’

Dr George Hay is the official historian of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission and author of the report of the special committee to review historical inequalities in commemoration.“The record keeping in the Indian army doesn’t appear to have been very good.

“They built the Neuve-Chapelle Memorial (in France). And we believe that it is representative. And it isn’t missing any names. So that’s definitely one category where it seems to have worked.

“What you then see across Africa, and particularly the Middle East, is another issue, bound up in decisions taken with the British Indian administration.

“Because these cemeteries and memorials are outside of Europe, they did not believe that the families of Indians will visit them.

“When it comes to Indian casualties, there is this two-tier system. If those men died in Europe, they would be treated in the same way or in accordance with their faith as everyone else. But if they died outside of Europe, principally if they died in Africa and in Mesopotamia, they are effectively treated almost as missing.

“So, memorials in Mesopotamia will have British officers and any Indian officers named. And then Indian NCOs and soldiers would be a number – say, 300 of a given regiment were killed.

“Over the last couple of decades, the commission has corrected almost all of those issues across Africa and the Middle East.

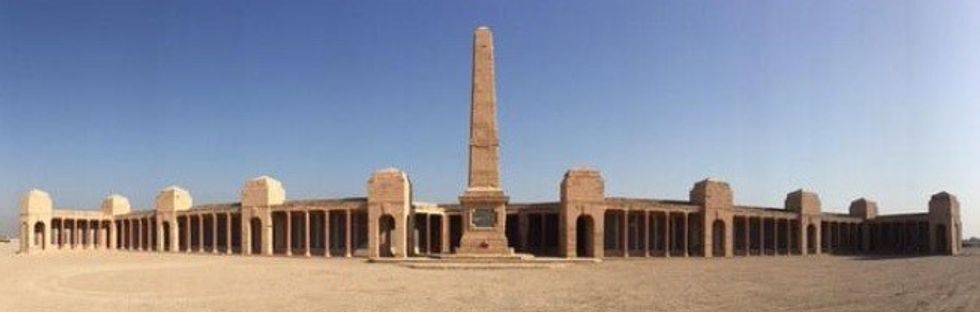

“In Basra, the one outstanding memorial hasn’t yet been corrected, which we know to have somewhere in the region of 30,000 (Indian) names attributed to it. Obviously, for reasons connected to security, we haven’t been able to get in and do anything to that one.

“In the case of Amara, we have 5,000 unidentified Indian burials. There were a number of hospitals. So Indian casualties who were coming back down the line from fighting subsequently died in those hospitals and were then buried in that plot.

“And the military authorities did not effectively mark their graves in a way that we can identify who those individuals are. Those men are then seen as missing.

“You have a relatively senior Indian officer who travels to Mesopotamia and is attached to the command there. There is no fuel to undertake cremation (of Hindu and Sikh soldiers). And so this is one of the reasons that is later claimed, that you make all these men missing.

“Everyone forward of Basra has been buried, and their graves haven’t been appropriately marked. This is the Indian Army that makes this decision. They say, ‘If we make them all missing, then we don’t have to deal with that particular problem (of identifying the graves later)’.

“So, what that leads to are grave registration units, which are another bit of the army effectively being told not to recover Indian dead in Mesopotamia and to focus almost entirely on the recovery of European dead.

“And, therefore, that’s why Indian missing statistics for Mesopotamia are so high.

“In most cases, their graves are entirely lost by the end of the war.”

‘I hope it will be widely read’

Dr Gavid Rand is a principal lecturer at the University of Greenwich; a member of the advisory committee set up by the CWGC; and an academic specialising on the history of the Indian army in the 19th century.“I think the report is overdue. It’s a serious, learned piece of work and shows very clearly that there were significant inequalities in the way in which Commonwealth and colonial soldiers were treated. I hope it will be widely read and help to start a much broader conversation about history, Empire and race in Britain.

“And that means recognising the enormous contributions made to Britain’s history by people from the subcontinent and from other parts of the Empire, not just in the First and Second World Wars, but to all of British history from at least the 17th century.

“It’s dreadful that children in this country are not exposed to informed teaching produced by working academics.

“Indians served on the Western Front. They then served in what we now call the Middle East. And there are various examples, particularly in the Mesopotamian theatre, where Indian soldiers’ graves were not marked, where bodies were not recovered and decisions were taken not to attempt to recover or to rebury bodies.

“So that is one example of where Indian soldiers were treated in a way that was different to European soldiers.

“There is some evidence there may be some under-reporting of Indian casualties in the Commonwealth War Graves database.

“In Mesopotamia, these would be soldiers who fell and were buried in temporary graves or indeed sometimes just left exposed on the battlefield or buried in mass graves. They could have been recovered and brought to a central place of burial.

“But there were some cases in Mesopotamia where decisions were taken not to attempt to recover bodies and bring them to a central grave.”