LORD SWRAJ PAUL, who turned 94 on Tuesday (18), has always enjoyed being called a “man of steel”.

To be sure, he has built a steel empire – beginning in the UK in 1968, expanding into India where he now has 25 plants in the automotive sector and then establishing the Bull Moose Tube group in the United States and Canada.

But he likes the phrase, “man of steel” for another reason. He stood by Indira Gandhi, when the Indian prime minister was written off as a political force after she lost the general election in 1977. She had become hugely unpopular not only in India, but also in the UK and many democracies after she imposed a state of emergency in 1975 and locked up thousands of her political opponents.

Paul proved he was not a fairweather friend, but someone with character – a man of steel – in continuing to express his support for the ousted prime minister when it was unfashionable to do so.

Marking his 94th birthday means Paul has witnessed many tragedies, some in his own life. “Grief is the price we pay for love,” the late Queen once said. They were not her own words – she was quoting the British psychologist, Dr Colin Murray Parks. In his 1972 book, Bereavement: Studies of Grief in Adult Life, he wrote: “The pain of grief is just as much a part of life as the joy of love; it is, perhaps, the price we pay for love.”

The sentiments, given wide currency by the Queen, certainly apply to Paul.

What brought Paul to Britain in 1966 was the desperate need to seek medical treatment for his daughter, Ambika, who was diagnosed with leukaemia. Those were the days when it was hard for Indians to get foreign currency. He believes that Mrs Gandhi cleared the bureaucratic rules for him, and for that gesture, he remained forever grateful to her.

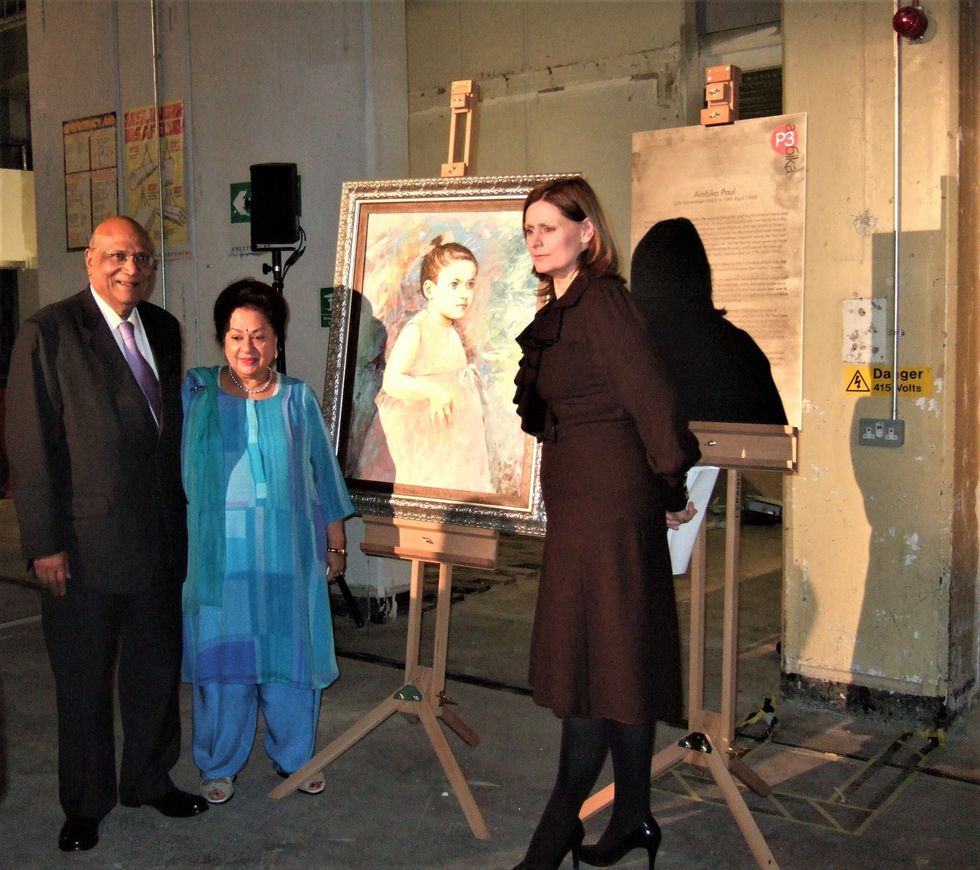

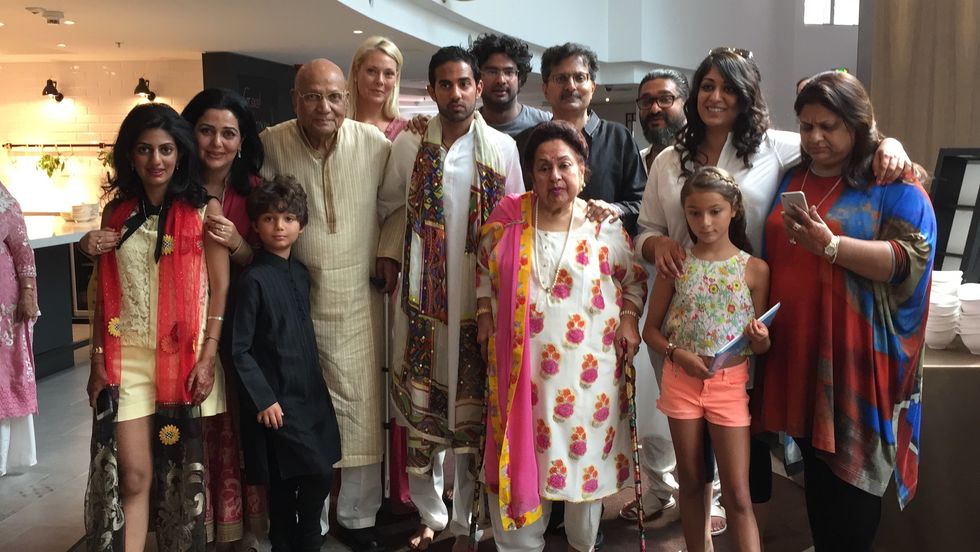

But when Ambika died in 1968, aged four, Paul and his wife, Aruna, could not face returning to India. The family then included their twin sons, Ambar and Akash, and a daughter, Anjli. Their youngest son, Angad, was born in London in 1970.

Paul would later rescue London Zoo when it was facing bankruptcy, because Ambika had enjoyed seeing the animals. His loyal support for the zoo has continued over the years – it is there that the peer hosts an annual tea party for several hundred family and friends.

He believed Angad was the most dynamic of his children, and made him chief executive of Caparo in 1996, but suffered a shattering blow when his son died in tragic circumstances in 2015, aged only 45.

He suffered another great loss in 2022, when Aruna passed away after 65 years of marriage. He had married her within a week of meeting her in Calcutta (now Kolkata).

There was another tragedy in 1990, this time in India, when his younger brother, Surrendra Paul, was assassinated in Assam by a terrorist group called ULFA (United Liberation Front of Asom).

In 1996, Aruna became Lady Paul after her husband was given a peerage when John Major was the Tory prime minister, and took the title, Baron Paul, of Marylebone, in the City of West minster. To friends, his down to earth wife remained Aruna. In 2002, Paul named a baby hippopotamus enclosure at London Zoo after her, and she registered a mock protest: “Other people name roses after their wives, but you have chosen hippos.”

“Pygmy hippos are much rarer,” the peer countered.

Anjli said her mother had been very supportive of her father: “She was dependent on him for obvious things like finance and running life at a sort of practical level. But I think emotionally he was probably more dependent on her than she was on him. He was in the limelight, but he wouldn’t have had the success he’s had without her.”

Swraj Paul was born into a Hindu Punjabi family in prepartition India in Jullunder (now Jalhandar) in Punjab on February 18, 1931.

“I was born into a manufacturing family that specialised in steel products,” Paul told Eastern Eye in an interview at his home in London.

“My father, Payare Lal Paul, was in this business for a long time,” he added.

He was named “Swraj” – meaning independence – “because Mahatma Gandhi visited our home around the time of my birth. India was fighting for independence then.”

He was only 13 when his father died, so he was brought up by his elder brothers, Stya and Jit, who sent him to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in the United States, where he gained valuable knowledge of metallurgy. After MIT, Paul returned to India and lived in Calcutta before Ambika’s cancer diagnosis forced him to move to the UK.

He recalled that in the traumatic days after Ambika’s death, he decided to settle in the UK. His first steel plant, making tubes, was in Huntingdon, Cambridgeshire, which was Major’s constituency. The second was in Wales in the Ebbe Vale constituency of Michael Foot, who would become leader of the Labour party between 1980 and 1983.

“When I started, I had very few resources, but I managed to build my first plant,” said Paul.

“It was inaugurated by Prince Charles. Later, Indira Gandhi inaugurated our second plant, and we went on to establish more in the US, Canada and other parts of the world.”

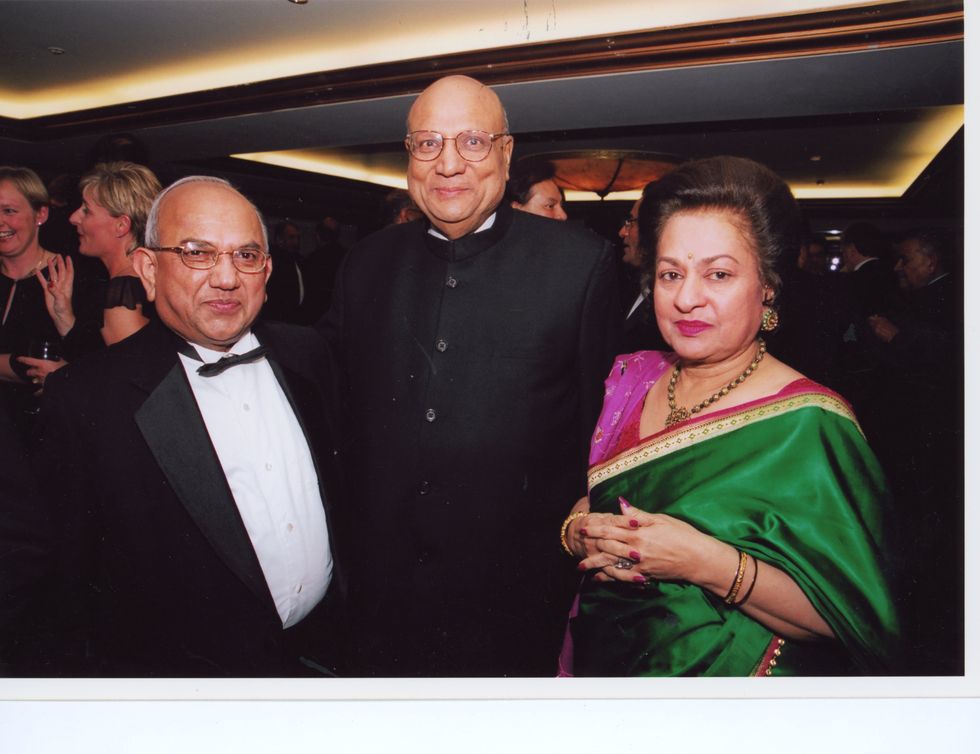

Paul is proud – with some justification – that he stood up for manufacturing at a time when the British economy was veering towards the services sector under both Labour and Conservative governments. He showed considerable diplomatic skills in retaining cordial relations with British prime ministers of all colours. At the same time, he played a role in strengthening relations between London and Delhi, long before the phrase “living bridge” became common currency.

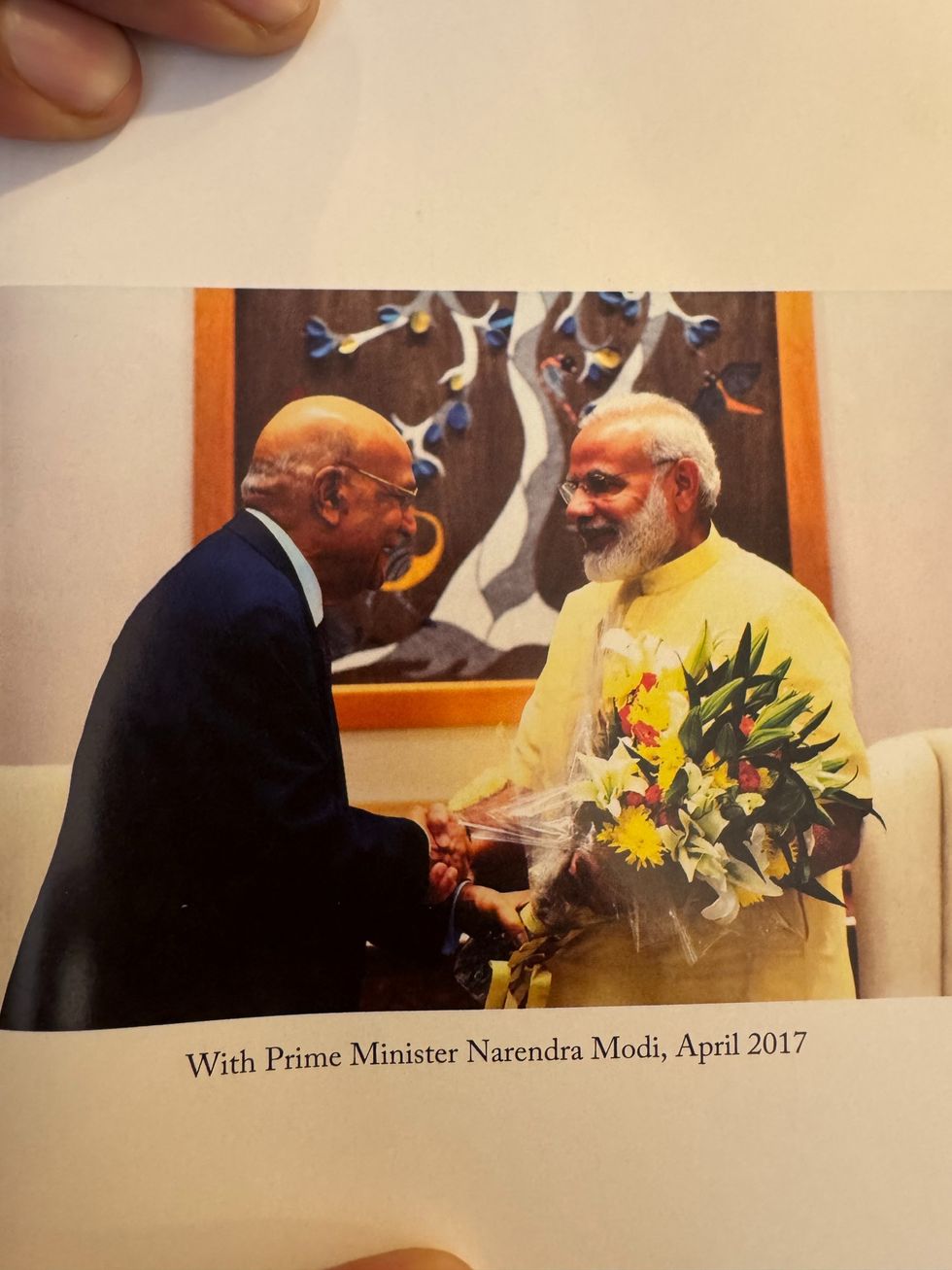

Although London has been his home since 1966, Paul would pay an annual visit to India and make it a point to meet the prime minister, president and key ministers of the day. And senior Indian politicians – and journalists – would call on him when they were in London. For a while he even ran an Indian restaurant, Sujata, where he would offer hospitality to his guests. They would first get a cup of tea if they met him at the Caparo headquarters in Baker Street. He himself has always been vegetarian.

Paul has witnessed history in both the UK and in India.

In 1966, Labour was in power, with Harold Wilson as prime minister. Margaret Thatcher was prime minister from 1979 to 1990, the first woman to hold the post. She was succeeded by Major, who was ousted by the Labour leader Tony Blair, who – like Mrs Thatcher – won three successive general elections. Blair was followed by Gordon Brown, with whom Paul retains the closest friendship.

Although he was initially a Labour peer, Paul is now a non affiliated member of the Lords. In any case, the Labour party’s historic links with India withered away after the death of Foot, who had inspired Paul to join the Labour party.

The changes in India were even more momentous. Indira Gandhi, who was prime minister in 1966, lost the general election in 1977, but swept back to power three years later.

“During Indira Gandhi’s tenure, I was honoured with India’s highest civilian award, the Padma Bhushan, for my contributions to business, presented by president Giani Zail Singh,” he said.

Her son, Rajiv Gandhi, took over when his mother was assassinated by her Sikh bodyguards in 1984. The age of global liberalisation was ushered in by Manmohan Singh in 1991 as finance minister in Narasimha Rao’s government. India’s rise as an economic power has continued under Narendra Modi who has been prime minister since 2014.

“Margaret Thatcher had a great fondness for me and often invited me for discussions,” revealed Paul. “On the Indian side, I worked with leaders, ranging from Jawaharlal Nehru and Indira Gandhi to Sonia Gandhi, Atal Bihari Vajpayee, Inder Kumar Gujral, Giani Zail Singh, Manmohan Singh, and now Narendra Modi. I have maintained good relationships with most of them.”

Many will remember the storm of protest from the domestic corporate sector in 1983 when Paul went to the Indian market and bought a large stake in two companies – Escorts Ltd and DCM (Delhi Cloth Mills). At that time Mrs Gandhi and Pranab Mukherjee, then the finance minister (and later president), were inclined to liberalise the Indian economy and invite foreign investment, especially from NRIs (Non-Resident Indians). But the government had to retreat in the face of determined opposition from the Indian corporate sector which did not want competition from outsiders.

If NRI investment had been allowed, “we would today be ahead of China”, claims Paul.

Though he lost the battle then, he says subsequent events proved him right – India was forced by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to liberalise in 1991.

The challenges he faced in the UK, where the steel industry was in crisis partly because of cheap imports from China, were just as great. Manufacturing was also generally in retreat.

Looking back on how manufacturing has shrunk, Paul told Eastern Eye: “Only God knows the future of British businesses. That is why I am expanding more in the US and in India. Last year, I visited my operations there (in the US). The UK needs more industries to ensure economic prosperity. I hope the prime minister, Sir Keir Starmer, will take stronger measures to support British industries.”

In North America, the company, known as Caparo Bull Moose Tube, “operates from seven plants – six in the US (Chicago, Elkhart, Gerald, Masury, Trenton and Casa Grande) and one in Canada (Burlington). Today the company offers one of the largest ranges of welded steel tubing in North America.

“Typical applications for Bull Moose Tube include construction, transportation, fire protection, agriculture, lawn and garden equipment plus many other engineering and household products.”

Then there is XL Specialised Trailers, which was acquired by Caparo in 2016, and is the second-largest player in the customised heavy-haul trailer market.

In the US, there is a property wing, whose projects include the boutique Angad Arts Hotel in St Louis, Missouri, commemorating his late son.

Caparo Middle East, based in Dubai, is “a distributor and trader of industrial, mechanical and electrical products”.

In Eastern Eye’s 2025 Asian Rich List, Paul was ranked 14th with £1.4 billion.

He has donated generously to Wolverhampton University where he has been chancellor since 1999 and which has a business school named after him. And its students’ union and learning centre is called the Ambika Paul Building.

He shared insights on his involvement in the London Olympics bid, stating, “I was responsible for overseeing preparations for the Olympic Games in 2012. We went to Singapore for the bid and made all the necessary arrangements with the then mayor of London, Ken Livingstone.

“Under the leadership of Gordon Brown and Tony Blair, we worked hard for British businesses. When Robin Cook was foreign secretary, I was appointed roving ambassador for British business.”

As a senior member of the Indian community in Britain, Paul paid tribute to Asian Media Group’s founding editor-inchief, Ramniklal Solanki, when the latter passed away, aged 88, on March 1, 2020.

“I know that in 1968, Ramnikbhai started Garavi Gujarat from his terraced home in Wembley,” said Paul.

“We were pretty much contemporaries. I was born on February 18, 1931. Ramnikbhai was born four months later in Surat in Gujarat on July 12, 1931. He arrived in Britain in 1964. I arrived two years later.

“Don’t forget the much smaller Indian community then was very different from what it is today. Some Indian immigrants had come looking for work, others to study, only a few for business. It was unfortunate circumstances that brought me to Britain. So we were looking out for each other, looking for people with whom we could get along.

“Ramnikbhai was one of those I learnt to respect. I remember going to his house for dinner. His boys, Kalpesh and Shailesh, were very small.

“The thing about Ramnikbhai was he led by example of how to be a good human being – he was a lovely man. Ramnikbhai and I connected at a personal level. He was a great family man – that is something we had in common. It encouraged affection and friendship.”

Paul hopes his children and grandchildren will safeguard his legacy.

He has not lost his sense of humour. Until a few years ago, he was the first one to arrive at his Baker Street headquarters. At a function in Leicester in 2019 where he was a receiving a lifetime achievement award, a friend wanted to know: “Why are you still working?”

Paul’s reply was typical: “At my age, what else can I do?”

Rachel Zegler as Snow White—caught between a fairy-tale and a cultural firestormInstagram/SnowWhitemovie

Rachel Zegler as Snow White—caught between a fairy-tale and a cultural firestormInstagram/SnowWhitemovie Disney’s CGI-heavy remake faces backlash for its overreliance on digital landscapesInstagram/SnowWhitemovie

Disney’s CGI-heavy remake faces backlash for its overreliance on digital landscapesInstagram/SnowWhitemovie Snow White (2025) joins the ranks of Hollywood’s most expensive, high-risk productionsInstagram/SnowWhitemovie

Snow White (2025) joins the ranks of Hollywood’s most expensive, high-risk productionsInstagram/SnowWhitemovie Box office predictions place Snow White among Disney’s most divisive live-action filmsInstagram/SnowWhitemovie

Box office predictions place Snow White among Disney’s most divisive live-action filmsInstagram/SnowWhitemovie The reimagined fairy-tale—does it still hold the same enchantment?Instagram/SnowWhitemovie

The reimagined fairy-tale—does it still hold the same enchantment?Instagram/SnowWhitemovie Gal Gadot commands the screen as the Evil Queen, exuding regal menace and icy charmInstagram/SnowWhitemovie

Gal Gadot commands the screen as the Evil Queen, exuding regal menace and icy charmInstagram/SnowWhitemovie Nostalgia vs. innovation—does Snow White find the balance?Instagram/SnowWhitemovie

Nostalgia vs. innovation—does Snow White find the balance?Instagram/SnowWhitemovie

Studio Ghibli’s hand-drawn worlds take years to perfect—can AI truly replicate the soul behind them?Ghibli Studio

Studio Ghibli’s hand-drawn worlds take years to perfect—can AI truly replicate the soul behind them?Ghibli Studio AI art tools can now mimic Ghibli’s signature style in seconds, raising ethical and creative concernsGhibli Studio

AI art tools can now mimic Ghibli’s signature style in seconds, raising ethical and creative concernsGhibli Studio As AI floods social media with “Ghibli-style” images, animators warn that true artistry can’t be automatedGhibli Studio

As AI floods social media with “Ghibli-style” images, animators warn that true artistry can’t be automatedGhibli Studio Hayao Miyazaki, the visionary creator behind Studio Ghibli, has crafted some of the most beloved animated films in historyGetty Images

Hayao Miyazaki, the visionary creator behind Studio Ghibli, has crafted some of the most beloved animated films in historyGetty Images The Firefly’s Glow AI can recreate the look of a Ghibli film, but can it ever capture the emotion behind it?Ghibli Studio

The Firefly’s Glow AI can recreate the look of a Ghibli film, but can it ever capture the emotion behind it?Ghibli Studio Miyazaki’s vision was built on painstaking hand-drawn artistry—can AI ever replicate the heart and soul behind his iconic films like Spirited Away and My Neighbor Totoro?Ghibli Studio

Miyazaki’s vision was built on painstaking hand-drawn artistry—can AI ever replicate the heart and soul behind his iconic films like Spirited Away and My Neighbor Totoro?Ghibli Studio Studio Ghibli’s animators spent months crafting each frame—AI, on the other hand, churns out “Ghibli-style” art in secondsGhibli Studio

Studio Ghibli’s animators spent months crafting each frame—AI, on the other hand, churns out “Ghibli-style” art in secondsGhibli Studio With AI mimicking Ghibli’s signature style, creators fear that the essence of the art form could be lost foreverGhibli Studio

With AI mimicking Ghibli’s signature style, creators fear that the essence of the art form could be lost foreverGhibli Studio From Totoro to Princess Mononoke, Miyazaki's hand-drawn masterpieces are irreplaceableGhibli Studio

From Totoro to Princess Mononoke, Miyazaki's hand-drawn masterpieces are irreplaceableGhibli Studio

Ravi B

Ravi B Rick Ram and Vanessa Ramoutar

Rick Ram and Vanessa Ramoutar