THOSE who pursue romantic love across boundaries of caste, religion or class in India are even today “just asking to be murdered”, says the historian Joya Chatterji, emeritus professor of South Asian History at Cambridge University.

She has given several examples of love leading to murder in her new book, Shadows at Noon: The South Asian Twentieth Century, which is a political, social and cultural history of India, Pakistan and Bangladesh over the past one hundred years.

What makes her book unusual is that she has woven the story of her own family into the larger history of the subcontinent.

In her acknowledgements, she thanks a long list of doctors: “This book would not exist but for Shane Delamont, neurologist at King’s College Hospital, London. He planted the seed by advising me to write the one ‘big’ book I had in me and to drop all other work.”

She goes on: “A small platoon of doctors kept me going as I wrote. I owe them more than I can say,” adding, “Farokh Udwadia saved my life just as the last chapter was in progress.”

Hers is certainly a big book – 842 pages. And a brilliant one that is a must read for British Asians.

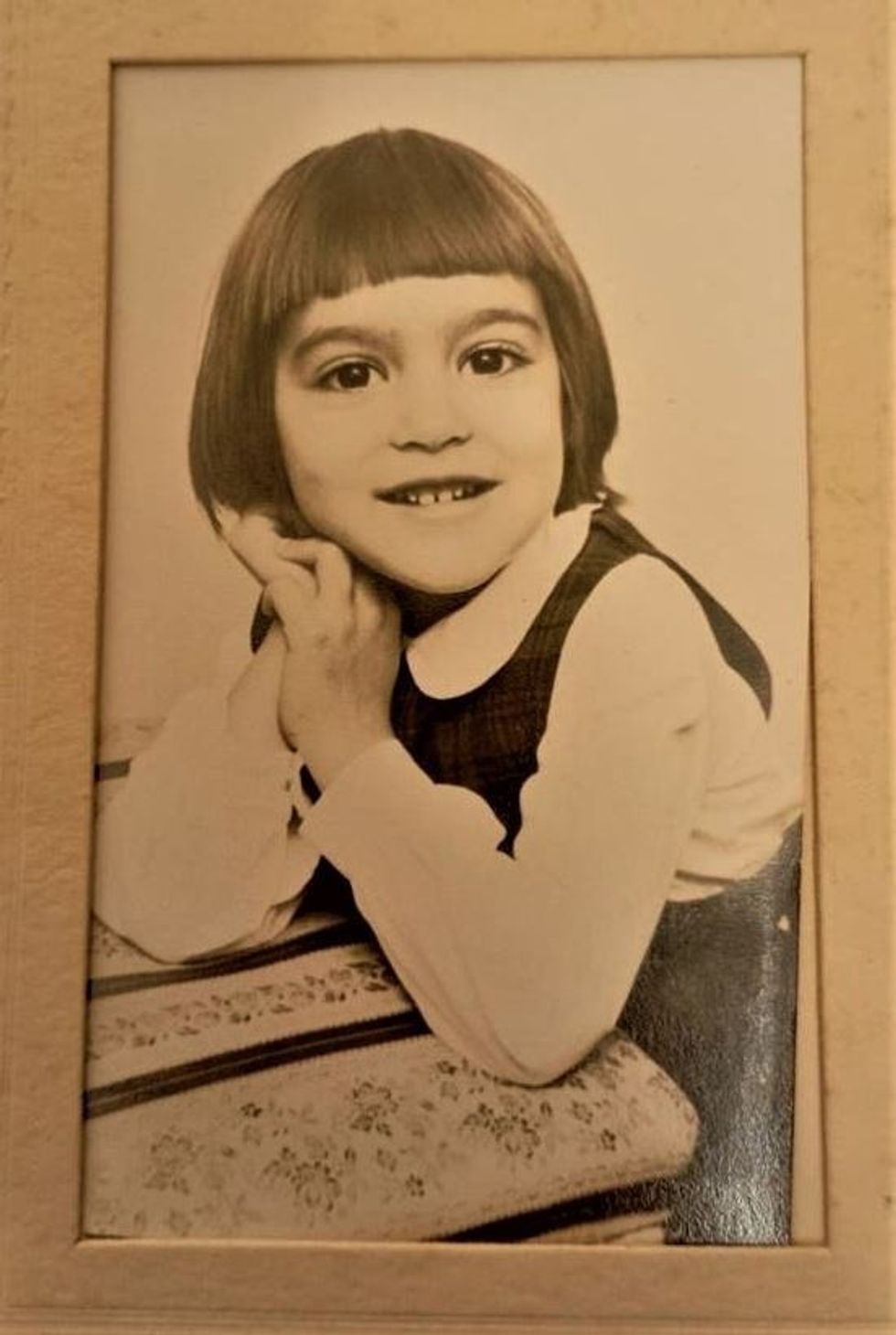

Joya (“Joy” to her five siblings among whom she is the second youngest) was born in Delhi in 1964 to a Bengali father, Jognath Chatterji, and an English mother, Valerie Ann Sawyer. She was passionate about history from a young age, came “first class first” in her exam results at Lady Shri Ram College, a well known institution for women in Delhi, and came in 1985 to Trinity College, Cambridge, where she did a three-year degree in two and then a PhD in the history of Hindu communalism in Bengal and where she is now a fellow.

Poor health forced her to give up day to day teaching in 2019, but she continues to supervise her PhD students.

She has students “from all over”, including India and Pakistan. “To some extent the students become part of my family. They WhatsApp me at all times of the day or night to discuss (for example) whether they should have abortions.”

Her Pakistani students, who had been taught nothing about why East Pakistan broke away from West Pakistan to form Bangladesh in 1971, were shocked when told the former constituted 55 per cent of the population of Pakistan.

“Are you sure? I mean, really?” they asked her.

Her “brilliant and beloved graduate students”, to whom Shadows at Noon is dedicated, kept asking her affectionately about her “bonker’s book” when she was writing it.

In order to talk to Eastern Eye, Joya made a special journey from home (which she shares with her husband and carer, fellow historian Anil Seal) to what she describes as her “Hogwartish” rooms at Trinity, tucked away in a hidden archway in a corner of the Great Court just past the college chapel. Apart from a spell teaching at the London School of Economics, she’s been at Trinity most of her adult life.

Joya admits she was always a curious child. By and by, she asked herself: “How did we become ‘Indians’, ‘Pakistanis’ and ‘Bangladeshis’ after the two great subdivisions of the subcontinent?” Another question was about “why people – who, for the most part, seemed intelligent and warmhearted – were so full of hatred towards certain groups in society.”

She remembers supposedly intelligent and educated journalists at the Times of India in Delhi “screaming and shouting” as they followed an India-Pakistan cricket match “as though it was war”.

One of the more gripping chapters sets out why love “continues to be a dangerous business in south Asia”.

Joya writes: “In her debut novel of 1997, The God of Small Things, Arundhati Roy writes of ‘Love Laws’ that lay down rules about ‘who should be loved, how and how much’. The list is long. One can break them in a host of ways – by transgressing prohibited degrees of kinship, by adultery, by crossing caste, class or religious boundaries, or by loving someone of the same sex or gender. All these forms of love meet severe social sanction, in some cases backed by the courts.

“Love across caste lines – particularly between ‘touchable’ and ‘untouchable’ castes remains perilous in the extreme. ‘Untouchables’ who dare to love ‘touchables’ risk their lives, and they know it. The barbaric custodial killing of Ammu’s Paravan Dalit lover, Velutha, in The God of Small Things rings true; the facts of South Asian life often being more brutal than fiction.

“And as for crossing religious boundaries, it became more fraught as communal tension heightened. In the late 1920s, a Muslim man named Mahiuddin Ahmed fell in love with his neighbour, Sovana Ray, the daughter of a distinguished Hindu lawyer of Barisal in eastern Bengal. In 1929 the couple eloped, marrying under Muslim law after Sovana converted to Islam. The police pursued them for months as the lovers moved from town to town across India. They c a u g h t them in the end, arresting Mahiuddin and sending Sovana to a rescue home. The court found ‘Mahi’ (as Sovana fondly called him) guilty of rape, abduction and conspiracy.

“Soon after partition, Nar e n d r a n a t h Nabis, a Hindu from Assam, fell in love with Suraiyya Begum, a Muslim from Burdwan district. The Hindu newspapers hounded them.

“In 2007, Rizwanur Rahman, a 32-year-old Muslim man from a poor family fell in love with a young woman born into a wealthy Marwari Hindu household. He had met Priyanka Todi at the graphics training school where he taught, and where students admired him for his teaching and kindliness. Both were adults. They married secretly under the Special Marriages Act. Priyanka moved to Rizwanur’s paternal home in a working-class neighbourhood. Priyanka’s family called in the police to force her to return to her parental home. She did this under duress. Soon afterwards, Rizwanur was found dead by the railway tracks. The police claimed that he committed suicide. Others believe that he had died after being tortured in police custody.”

Joya gives her take on arranged marriage: “Let’s get one thing clear at this point. The new nuclear family was not based on love. These spatial reconfigurations of the household did not mean that pre-marital passion became socially acceptable. Outside a tiny bubble, love was, and still is, regarded as the greatest moral threat to dharma (duty), to honour (izzat), and to the order of things. Love before marriage brings shame upon both households and the lovers themselves. It is understood as lust: a vice. As one character puts it to his son in Pakeezah (the film that Meena Kumari was shooting when she encountered the dacoits in central India), his lover ‘is not our daughter-in-law. She is your sin.’

“True love, in this moral world, grows and matures only after marriage, within the household. It is shaped, above all, by duty. It is only by parents choosing their son’s bride that their authority over him remains intact: it is therefore essential that they arrange his marriage. If he ‘loves’ his wife-tobe before marriage, he will be torn between her and his parents. He will no longer be a reliable and obedient son. His mother’s command over his wife (and her other daughters-in-law, bahus) will be diminished, and that will upset established hierarchies.”

Joya tells Eastern Eye that instances of couples being hounded are so common that they have stopped being newsworthy. “It’s so frequent that we don’t even notice when we read in the paper that people are abducted, arrested, the girl is returned to her home. The guy ends up dead. It takes guts to love someone in India. There’s this whole concept of hum bhag jayenge (we’ll run away). You can’t bhago (run away) anywhere very far without being tracked down.”

She elaborates: “There’s this strong belief that if a son marries for love, the household’s authority over him is lost, then he will only do what his wife wants, and then, oh, my God, the whole structure is shaken. The family needs to have patriarchal control over the boy. “The newest bride is the weakest person in the structure of a joint or Hindu household because she’s got no allies.

“And this whole love business is for somebody else. It may be for the elite. It is also for the very poor. Why? Because it avoids having to give dowry.”

In her own case, when she married Prakash, her first husband – they went on to have a son, Kartik – members of her own family were not happy. This was because Prakash, who was from a village, was not in her class. It would take a number of years before her father, to whom she was very close, would be reconciled to his daughter’s marriage.

Joya recalls that Prakash “was the first person in his family to get a BA, MA, PhD, a highly intelligent man. I met him in the library. But there was this class issue. My father was an extremely liberal person, but people all around him were shocked by my behaviour, my lack of choice, my lack of discernment. Surely, (I thought) they could see that in a meritocratic sense, he has made his way in life. They couldn’t actually see it.”

What makes her book accessible are the many cultural references in it. Books she refers to include Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses; Vikram Seth’s A Suitable Boy; Nirad Chaudhuri’s The Autobiography of an Unknown Indian; Amitabh Ghosh’s The Shadow Lines; and The Prisoner by Omar Shahid Hamid, a former Pakistani policeman.

She also makes many arguments using messages in movies: Satyajit Ray’s trilogy, Pather Panchali, Aparajito and Apur Sansar (“among the best films you will ever see”); the Amitabh Bachchan and Rekha starrer, Silsila; Do Bigha Zameen; Mother India; Umrao Jaan; Devdas; Sahib, Bibi aur Ghulam; Sholay; Hum Aapke Hain Kaun; Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge; and LOC: Kargil.

If she were marooned on a desert island, the five books Joya would take would be Bleak House by Charles Dickens; Vladimir Nabokov’s Speak, Memory; Anuradha Roy’s Sleeping on Jupiter; Middlemarch by George Eliot and Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice. The films she selected are all Indian: Ray’s Apur Sansar and Charulata; Pakeezah; Guru Dutt’s Pyaasa; and Mani Ratnam’s Bombay.

So far as the teaching of history in British schools is concerned, she is a member of the core project team that has set up a website, “Our Migration Story: The Making of Britain”.

Over the years, she has urged the BBC and other TV networks to “make partition a British story. Migration has been introduced on to the GCSE syllabus and then the A level syllabus. That includes the fact that there are people who are not Caucasians in Britain, how they’ve been coming over, waves and waves. But it’s taken years and years and years of effort. It’s been a goal of my life to make people wake up, and say, ‘Hang on. There are people here in Britain who happen to be Punjabis and Bengalis. Why would that be so? Do you think it might be something to do with partition?’”

However, she reckons it’s too soon to deal with Winston Churchill’s perceived imperialism and racism: “I now pass the baton on. Younger people have taken taking up the fight. We have to first win this battle (over migration), before we can win Churchill. He is God-like. You should see the reactions because a few of my students run outreach classes for students trying to get into Cambridge from the state sector. And one or two of them have done classes on Churchill. It is basically to teach them how we do history. It is an incomplete, complicated subject, in which there are no clear baddies and goodies. They practically had stones pelted at them for suggesting that Churchill was in some way implicated in the Bengal famine, which he was.

“If you read The Hungry Empire: How Britain’s Quest for Food Shaped the Modern World by Lizzie Collingham, which is a marvellous book, she talks about the extent to which Churchill’s famine policies in India were driven by the need to feed Britain. He did avert starvation in Britain. In the meantime, we guys (back in Bengal) starved – he prioritised the white man over the brown man.”

In Shadows at Noon, she says: “I suggest that India and Pakistan had more in common than is often understood.”

She has not been able physically to do as many interviews as she would have liked for her book. “For this reason, I have used vignettes of autobiography, family lore and my own life history. I have interviewed myself, dredging out memories, recognising they are as labile as the memories of others. My grandparents were born in the 1880s, my father in 1921, his sister in 1913; and many cousins, nieces and nephews were midnight’s children, born around the time of independence and partition.

“My own siblings and I arrived in the 1950s and 1960s. We started to produce the next generation in the 1980s and 1990s. So this family, like so many, has seen the century and has stories to tell about it. This book is my personal discovery, not of India, but of a divided subcontinent that was once called India.”

“I seek to soar above a subcontinent partitioned by politics and states and observe with a bird’s eye, its shifting patterns of light and shadows. I recognise that my knowledge of the subcontinent is uneven: I know some parts of it like the back of my hand but others only through secondary work.

“I have resorted to a parallel archive of amateur films, documentaries, feature films, photographs, stamps, newspaper clippings, private papers, maps, genealogies, handicrafts, calligraphy, amulets, and collections of objects from different places. A lifetime of reading, thinking, teaching and learning from students at the cutting-edge of their subjects helped me envisage this book.”

Shadows at Noon: The South Asian Century by Joya Chatterji has been published by The Bodley Head. £30

James Gunn introduces a surprising new element to the Fortress of Solitude: cape-wearing AI doctorsDC

James Gunn introduces a surprising new element to the Fortress of Solitude: cape-wearing AI doctorsDC In a dramatic opening scene, a wounded Superman depends on his loyal dog, KryptoDC

In a dramatic opening scene, a wounded Superman depends on his loyal dog, KryptoDC

Legendary actor Manoj Kumar passed away at 87, leaving behind an unmatched legacy of patriotic cinemaInstagram/

Legendary actor Manoj Kumar passed away at 87, leaving behind an unmatched legacy of patriotic cinemaInstagram/ Fans and admirers mourn the loss of Manoj Kumar, whose films once stirred the nation’s soulInstagram/

Fans and admirers mourn the loss of Manoj Kumar, whose films once stirred the nation’s soulInstagram/ A legendary face of Indian cinema — Manoj Kumar’s timeless contributions shaped Bollywood’s golden patriotic era

Instagram/1000thingsinludhiana

A legendary face of Indian cinema — Manoj Kumar’s timeless contributions shaped Bollywood’s golden patriotic era

Instagram/1000thingsinludhiana

The nation remembers Manoj Kumar, whose stories of sacrifice and pride became part of India’s cultural memoryInstagram/

The nation remembers Manoj Kumar, whose stories of sacrifice and pride became part of India’s cultural memoryInstagram/