ALTHOUGH Shah Rukh Khan made his Bollywood debut in 1992, it was his 1993 release Baazigar, which gained him big global attention.

His dastardly portrayal of a duplicitous individual, who goes on a murderous revenge mission, kick-started a rapid rise to the very top of Hindi cinema for the actor. It also showed that he was a new kind of leading man, who was willing to do things differently and play a negative role. That is why this film will be celebrated by his global fanbase on its 30th anniversary on November 12.

Eastern Eye decided to mark three decades of the movie with 30 fun facts connected to it.

- Baazigar was an unofficial remake of Hollywood film A Kiss Before Dying (1991), which itself was an adaptation of a 1953 novel of the same name. There had also been a 1956 American movie with the same title.

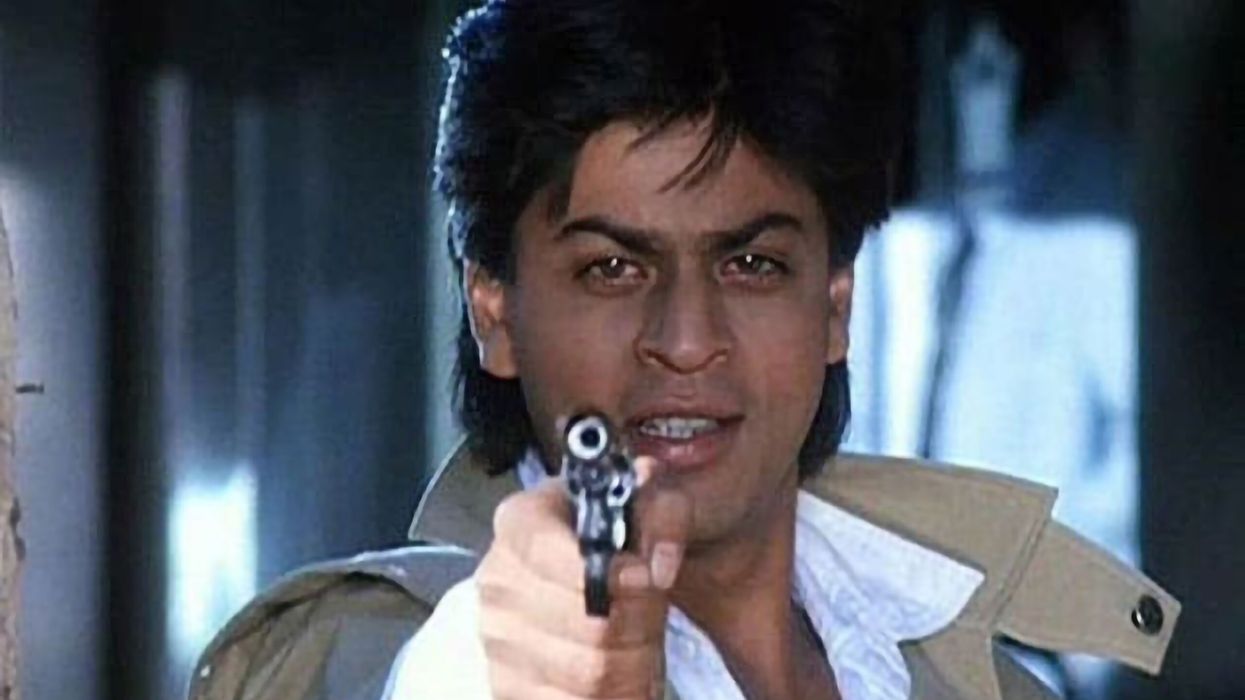

Scenes from the film

- Years later, actor Deepak Tijori alleged that he had originally shown the Hollywood film to directing duo Abbas-Mustan and producer Pahlaj Nihalani in the hope they would make it with him in the lead role. They were impressed with the subject but opted to produce the movie without him.

- A number of actors including Akshay Kumar, Salman Khan and Anil Kapoor turned down the lead role because the character was villainous.

- Abbas-Mustan wanted the writers to narrate the story to Shah Rukh Khan, but he insisted the duo do it themselves. They said: “When we finished, we expected him to say the usual, ‘I’ll think about it and let you know in two days.’ But he jumped up and said, ‘I’m doing the film’ and started showing us how he would enact certain scenes.”

- The mother track in the story with Rakhee was introduced later into the movie to add extra emotion and sympathy for the villainous protagonist. AbbasMustan had said: “If the mother-son relationship is explored and justified properly on screen then it definitely strikes a chord with audiences. If a son is taking revenge for his mother, then his everything is forgiven. And it worked well with the audience.”

Another promo image

- Shooting for Baazigar was supposed to commence in full shortly after the launch in December 1992, but Mumbai communal riots caused by the Babri Masjid destruction prevented that from happening.

- The film finally started shooting in March 1993 and wrapped up by May-June. It was supposed to be in cinemas for July, but was finally released later that year in November.

- Although Shah Rukh Khan had got noticed with 1992 films like Deewana and Raju Ban Gaya Gentleman, Baazigar became the big turning point in his career and put him on the radar of bigger banners.

- Baazigar was the first film starring Shah Rukh Khan and Kajol. They would go onto act together in record breaking films like Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge (1995) and Kuch Kuch Hota Hai (1998).

- The directors initially considered casting Sridevi in a double role, before opting for newcomers Shilpa Shetty and Kajol to play the sisters.

- Ayesha Jhulka had starred in AbbasMustan hit film Khiladi (1992) and was approached for Kajol’s role, but she declined it.

- Juhi Chawla turned down the role that was played by Shetty because she didn’t think it was substantial enough. Madhuri Dixit also declined the same role and so did Madhoo, who said, “I didn’t do Baazigar because I was doing some other movie”.

Shah Rukh Khan withKajol and Shilpa Shetty in a promo image of Baazigar.

- Siddharth Ray, who played the key police inspector role was the grandson of filmmaking legend V Shantaram. He sadly died in 2004 aged just 40.

- Shetty made her debut in the film and signed for it without auditioning. The actress would have cosmetic surgery after the movie and appeared in her next film with a different looking nose.

- Shetty revealed that her first shot was for the song Ae Mere Humsafar and said Shah Rukh Khan taught her about how to face the camera.

- Musician Daboo Mallik, who is the father of popular music stars Armaan Malik and Amaan Mallik, played a small role in the movie.

- Two endings for Baazigar were filmed, including one where Shah Rukh Khan’s character is arrested. But they opted for the more dramatic one where both he and the villain die.

- In another version, Priya (Kajol) was supposed to kill Ajay (Khan), like in the original plot, but they opted not to use it.

- The famous Shah Rukh Khan contact lens scene was inspired by something similar that happened in classic movie Satte Pe Satta (1992), with Amitabh Bachchan.

- Most of the comedy by Johnny Lever was improvised in the film. Shah Rukh Khan also improvised scenes to add more intensity to his role.

- Many years later, Gauri Khan revealed that she had designed her husband Shah Rukh Khan’s eyecatching look in the song Ye Kaali Kaali Aankhen.

- A lot of musicians and DJs have sampled the Baazigar song Yeh Kaali Kaali Aankhen, including M.I.A on her Matangi Mixtape.

- The song Saamajh Kar Chaand was filmed, but edited out of the final cut because the directing duo felt the film was too long.

- With over 10 million units sold, Baazigar became one of the bestselling soundtracks of 1993.

- There was a 1990 magazine promotional image of the film Jurm that featured Vinod Khanna wearing sunglasses, with a picture of Meenakshi Sheshadri on one lens and Sangeeta Bijlani on the other. The idea was recreated for the Baazigar poster with Shah Rukh Khan, Shetty, and Kajol. The same concept would later be used in some Hollywood films.

- The romantic thriller was released 42 days before blockbuster hit Darr, which was the second movie to see Shah Rukh Khan successfully play a villainous role.

- Despite obviously being inspired by A Kiss Before Dying, Robin Bhatt, Aakash Khurana and Javed Siddiqui won a Filmfare Best Screenplay award for Baazigar.

- The movie also won Filmfare awards for best actor (Shah Rukh Khan), best male playback singer (Kumar Sanu for Yeh Kaali Kaali Aankhen) and best music director (Anu Malik).

- Baazigar became the fourth highest grossing film of 1993 after Aankhen, Khalnayak and third placed Darr.

- Baazigar was later remade in Telugu as Vetagadu (1995), in Tamil as Samrat (1997) and as Kannada film Nagarahavu (2002).

Scenes from the film

Scenes from the film Another promo image

Another promo image Shah Rukh Khan withKajol and Shilpa Shetty in a promo image of Baazigar.

Shah Rukh Khan withKajol and Shilpa Shetty in a promo image of Baazigar.