By Amit Roy

AUTHOR Andrew Lownie has spoken to Eastern Eye about his so far unsuccessful four-year battle with Southampton University to secure access to the letters and diaries of Lord Louis Mountbatten, the last Viceroy of India at the time of Partition in 1947, and his wife, Lady Edwina Mountbatten.

Southampton University, which bought the papers a decade ago using public funds to the value of £4.5m, should not, in theory, quibble about making them available to researchers and scholars, Lownie says. But the university claims it has been ordered by the Cabinet Office to keep some documents secret.

Lownie argues the government has no business getting involved in what should or shouldn’t be made public by an educational institution dedicated to learning and scholarship.

Lownie told Eastern Eye he detects the influence ultimately of the royal family behind Southampton’s decision to make it as difficult as possible for him to get access to all the documents. After all, Mountbatten was an uncle to the late Prince Philip and great uncle to Prince Charles.

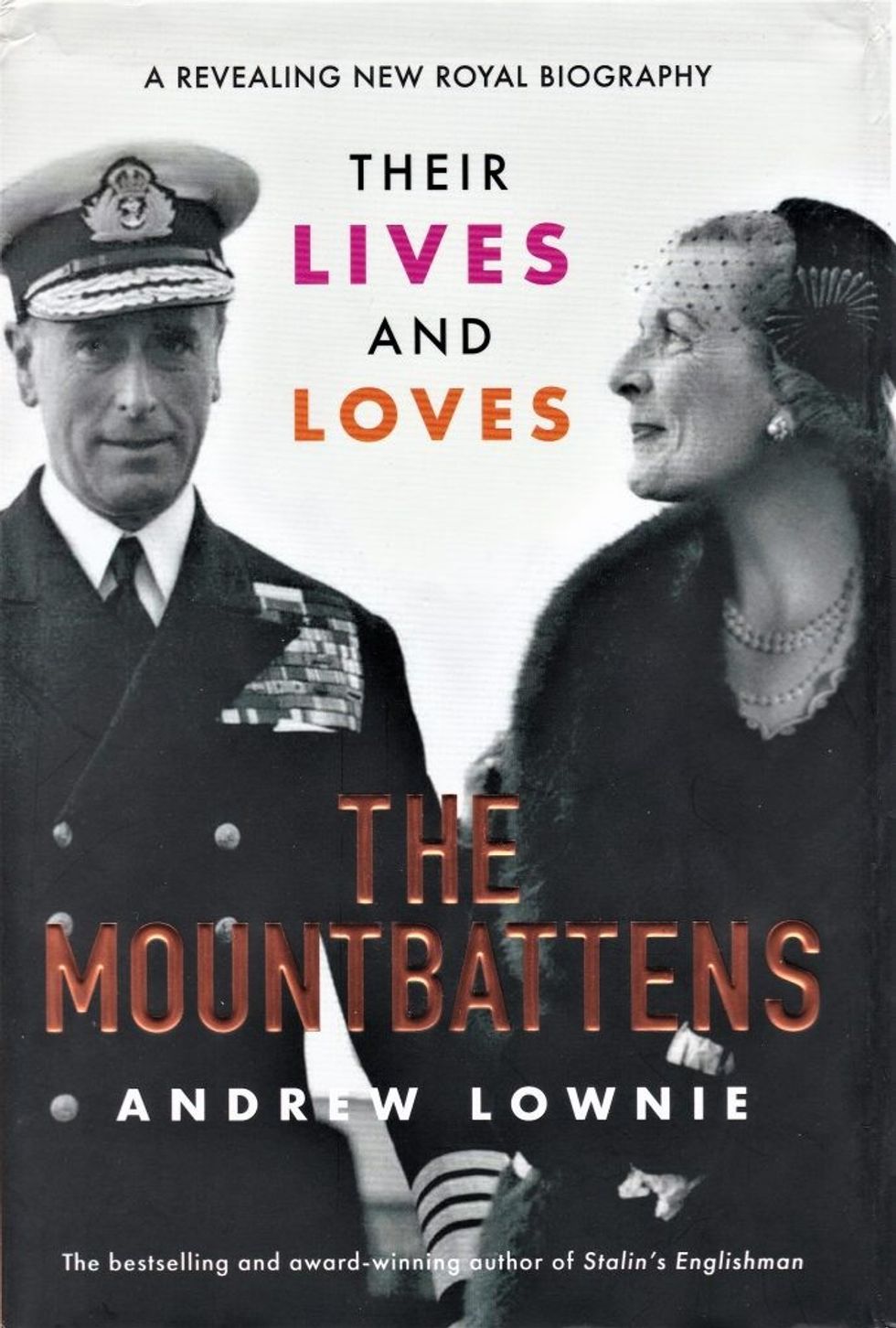

In his biography, The Mountbattens: Their Lives and Loves published last year, Lownie painted a portrait of an unusual, but intimate marriage, in which “Dickie” and Edwina took lovers outside marriage. Unlike other Mountbatten biographers, Lownie also took the view that Edwina’s relationship with Jawaharlal Nehru, independent India’s first prime minister, was rather more than platonic.

It is possible that the Cabinet Office fears publishing the most sensitive documents might harm Britain’s relationship with India or Pakistan. The true nature of Nehru’s relationship with Edwina also remains a delicate subject. “There are claims that there are references to India and Pakistan,” said Lownie. “That is one of the objections.”

He added: “I’m only speculating here, but there may be stories about pressure being put on him (Mountbatten) perhaps by the princes or by Nehru. Who knows (but there were) the debates about Kashmir and all the other issues of the boundary. There’s a lot of important political information, I suspect, in these diaries, the relationship they (the Mountbattens) had with Indian leaders, what they really thought of (founder of Pakistan, Muhammad Ali) Jinnah.

“I suspect there’s some disparaging comments made perhaps by Edwina in the 1950s.”

Asked why the Cabinet Office got involved, Lownie said: “This is what’s so weird because these are private diaries. The Cabinet Office have muscled in and claimed that these are documents of a public figure and therefore they have a say in it.

“It’s a great mystery. I think what is beginning to emerge (is this) – we had a letter last week from the Cabinet Office saying they’re under pressure from the royal family. So the royal family are behind this.”

Lownie’s solicitors, Bates Wells, have posed a barbed question to government lawyers: “It is not clear why the fact that a private diary contains a reference to the royal family makes it necessary to seek approval of the royal household prior to publication.”

A University of Southampton spokesperson said: “As part of the allocation of the archives in August 2011, the university was directed to keep a small number of the papers closed until we were otherwise advised. The university has always aimed to make public as much of the collection as is possible while balancing all its legal obligations.’’

It may be one thing for the university to deny full access to Lownie, who has spent £250,000 of his own money in his legal battle with the university and is trying to raise further resources through crowd justice. But it would be quite another if Indian or Pakistani historians were to request sight of the withheld letters and diaries. Refusal would raise the tricky question: “Whose history is it anyway?”

The Mountbatten letters and diaries were initially loaned to the university in 1989, but were bought in 2011 with the help of grants of almost £2 million from the National Heritage Memorial Fund and £100,000 from Hampshire county council. It was also subject to the “acceptance in lieu” scheme under which art works and archives are accepted by the nation in lieu of inheritance tax, taking the total cost to about £4.5m, according to Lownie.

Chris Woolger, professor of history and archival studies at the university, said at the time: “It is impossible to underestimate the archives’ historical and national impact; in particular, without them we would find it difficult to understand fully the foundations of the independent states of India, Pakistan and Bangladesh.”

Lownie has used the Freedom of Information Act to try to get access. Southampton University and the Cabinet Office have lodged an appeal against a ruling from the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) that all the documents should be made public. The university has released 10,000 pages of documents but these go only up to 1934 – and have been edited.

Lownie said: “The diaries run to 47 volumes for him and 36 for her, plus 59 files of correspondence so this is a tiny percentage (of the archives).”

In a witness statement to the courts in December last year, Lownie stated: “On 28 April 2017, I wrote to Karen Robson, archivist at the university, requesting access to ‘the retained papers of Lord and Lady Mountbatten which include …. the diaries of Lord Mountbatten (47 volumes, 1920-68), the diaries of Lady Mountbatten (36 volumes, 1921-1960), the correspondence between them (59 files), the letters from Lady Mountbatten to Jawaharlal Nehru (33 files, 1948- 1960), former prime minister of India, along with copies of his letters to her (15 files, 1947-1960)”.

The statement went on: “Initially in May 2017, the university simply told me that the diaries of Lord Mountbatten, the diaries of Lady Mountbatten, and the 59 files of correspondence between them ….were ‘closed to public access’ under a 2011 ministerial direction policed by the Cabinet Office.”

There is more than a suggestion the university’s academics wanted to do a book themselves ahead of Lownie: “Then, to my surprise, I discovered that in January 2018 the university had sent a proposal to the Cabinet Office seeking to allow it to publish an edition of the 1947-48 diaries of Lord and Lady Mountbatten along with accompanying commentary by university staff, rather than allowing me to access this under FOIA for the purpose of my book.”