Virtual event offers 'joy of interaction unfettered by borders and itchy censors'

THE actor Kabir Bedi and author and historian Victoria Schofield spoke of dealing with tragedy and pain during the Khushwant Singh Literary Festival (London) last weekend.

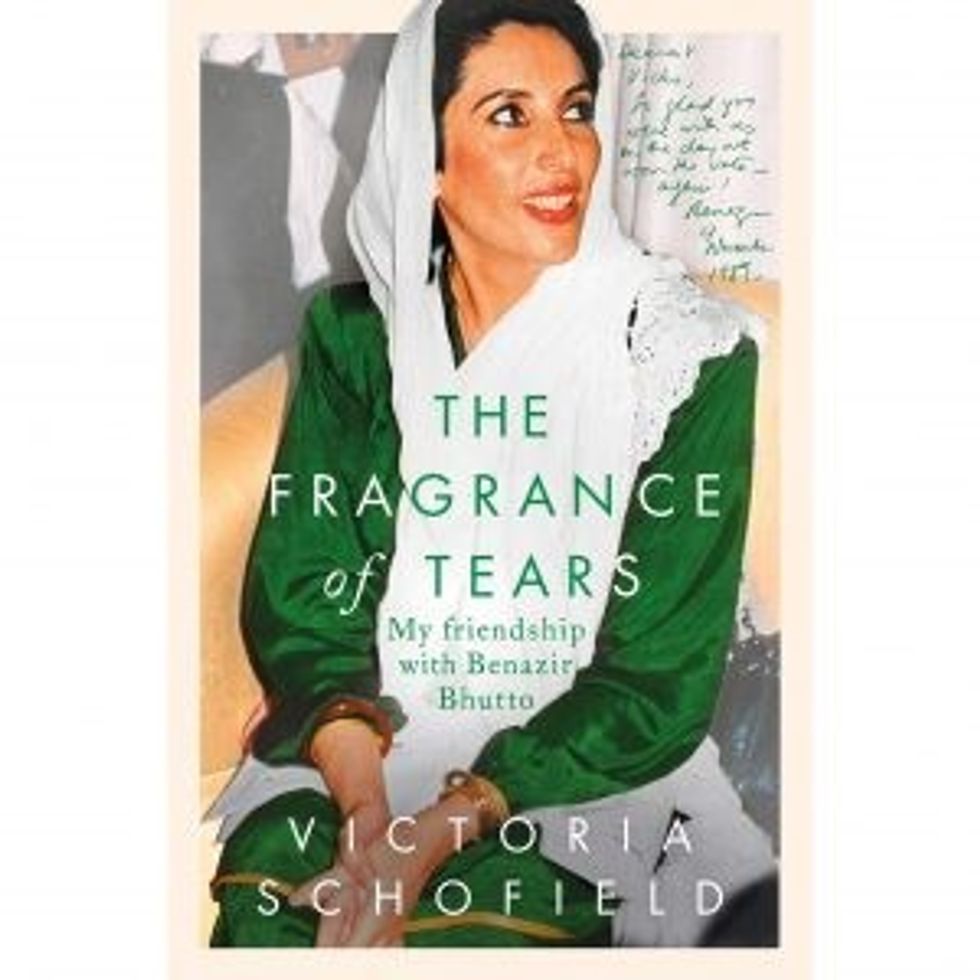

They were discussing their books – Stories I Must Tell: The Emotional Journey of an Actor and The Fragrance of Tears: My Friendship with Benazir Bhutto respectively – at the virtual event last Saturday (26) and last Sunday (27). Eastern Eye is a media partner.

Recalling the worst personal tragedy of his life – his 26-year-old son, Siddharth, took his own life – Bedi said: “What happens when a son comes to his father and says, ‘I’m thinking of committing suicide.’ What do you do? How do you deal with it?”

He admitted writing the book and dealing with the death of his son, who had been diagnosed with schizophrenia, was very difficult, but in order to give an honest account, “it was necessary”.

“That revisitation itself was dramatic in its own way because it reopened wounds that had actually become scars. I had to relive that whole experience. And in this pandemic, so many people have lost loved ones. There’s a sort of mourning going on. But at the end of the day, the healing has to begin. We have to find ways of moving on with life, and honouring the memory of the dead because the dead would want us to live.”

Bedi, who has been married four times, owned up to mistakes he made: “One of my achievements is that I’m able to remain friends with my ex-wives – because as any divorced person will tell you – that’s not an easy thing to do.”

Meanwhile, Schofield described her emotions visiting the grave of her close friend and former Pakistan prime minister, Benazir Bhutto, who was assassinated in 2007. She revealed it was Benazir who had introduced her to the great Sindhi poet, Shah Abdul Latif, one of whose poems inspired the title of her book: “The sorrowful smell of the mist lingering over the Indus,/ Gentle waves of rice, dung and rind,/ It is the salt cry of Sindh./ As I die, let me feel the fragrance of tears.”

The poem came to her as she visited Benazir’s grave in Garhi Khuda Bakhsh in Larkana district, Sindh, in Pakistan. She and Benazir, who first met as undergraduates at Lady Margaret Hall at Oxford in 1973, remained friends for 33 years until the latter’s death in December 2007.

It was also revealed that as a tribute to the English primatologist and anthropologist, Dame Jane Goodall, 100 trees are being planted in the Sunderbans tiger swamps. Goodall, the author of The Book of Hope: A Survival Guide for Trying Times, was interviewed by NDTV news anchor Gargi Rawat.

The first session – a discussion between the Columbia University professor Vidya Dehejia and author William Dalrymple – was introduced by the Pakistani historian Fakir Aijazuddin.

He pointed out that having a literary festival being held virtually for the first time, had advantages: “We can share the joy of being able to interact like this unfettered by borders, visas or itchy censors.”

Khushwant Singh, journalist, author and scholar, was born in Hadali, Punjab, now in Pakistan, on February 2, 1915. He died in Delhi, aged 99, on March 20, 2014.

The literary festival, set up by his journalist son, Rahul Singh, seeks to keep alive his father’s legacy, especially his lifelong mission to foster warmer relations between India and Pakistan. Its theme in the year of the pandemic is taken from the John Donne poem, No Man is an Island.

Aijazuddin said: “My last homage to Khushwant Singh was to bring his ashes for interment in 2014 in his birthplace at Hadali. To him, there were no iron curtains, no bamboo curtains, no saffron curtains.

The only curtain that mattered to him was the cloth one that hung in his flat in Sujan Singh Park (in Delhi). It had been given to him by his dear friend Manzur Qadir (a Pakistani jurist and politician) and printed with the text in Arabic of the Kalimas (the basic beliefs of Muslims all around the world).

“By hanging it at the entrance of his flat, he wanted visitors of different religious persuasions to realise that by passing through it, they would not lose caste nor have to abjure their own religion. He was the quintessential humanist.”

Schofield’s account will give readers a better understanding of what it was like for a woman to become prime minister of Pakistan for the first time when she was 35 and had just had a baby. “I saw people refuse to shake her hand. The mullahs were preaching against her. But she set an example because at that time you didn’t see women television presenters or doctors or lawyers the way you see now. That’s part of her legacy.”

Her book is not a conventional biography, but the intimate story of their friendship. After Benazir’s death, “people were saying, ‘Oh, you should write her biography, you’re so close to her, you’d do a really good job.’ But to be honest, when she actually was assassinated, I set it aside.

The events were too raw, too painful. I would not do a good job on a biography because I don’t think it’s fair for a biographer to have been as close as I was.

“But what I lost in terms of the biography I gained in terms of insights and proximity, and that’s what I felt was important. I wrote the first sentence on a train on New Year’s Day in 2019. There was no going back. The book starts with a narrative of when I heard of her assassination.”

When they first met at Oxford, Schofield “had no idea she would make such a huge impact on my life. In the Oxford chapters, I wanted to give a flavour of what she was like as a student and how our friendship developed. She was very popular. She zoomed around in her yellow MGB sports car which so many have written about. And these Oxford friends, as they are called, appear as a sub-theme throughout my narrative. It was among the Oxford friends she had been the happiest, and she could just relate back to them.”

Schofield first visited Pakistan and spent nearly a year there while Benazir was under house arrest before her father, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, was hanged by the military dictator, General Zia-ul-Haq, in 1979. When Schofield wanted to return, she found she had been banned from entering Pakistan “by land, sea or air”.

Schofield, who was then making programmes for BBC radio, was deported to India. “I sometimes do get accused of being a bit pro-Pakistan. I am very pro-Pakistan. I’m also very pro-south Asian, and very pro-India. Soon afterwards, I was due to have an interview with Indira Gandhi. And I was terrified the interview would be cancelled. The first thing she said to me was, ‘So they did not allow you into Pakistan.’ And I said, ‘No, Prime Minister, I’m afraid not.’ She said, ‘Never mind. You’re welcome here in India.’”

Schofield was with Benazir when she survived an assassination attempt on her bus in October 2007, a few weeks before she was killed. “It somehow flashed across my mind that we had this extraordinary friendship. I just wanted to leave something with the children for posterity. I’ve dedicated the book to my three children and to her three children.”