BOYS from the Blackstuff is a play set in Liverpool in 1982 about five unemployed men who are desperate to find work, but who cannot find any.

Directed by Kate Wasserberg, it is an adaptation by James Graham of the 1982 BBC TV drama by Alan Bleasdale, a playwright from Liverpool and is on at the Olivier at the National Theatre.

The five men are Chrissie (Christopher Robin Todd); Loggo Lomond; Dixie Dean; George Malone; and Yosser Hughes, the most traumatised of the group, given to headbutting anyone he considers an enemy.

The present production of Boys from the Blackstuff, which was staged at Liverpool’s Royal Court in September last year, will transfer to the Garrick Theatre after its brief run at the National.

The “blackstuff” is slang for the tarmac laid by the men, who often eulogise their expertise in song:

Oh we laid it in the harbour and we laid it on the flat;And if it doesn’t last for ever then I swear I’ll eat my hat; I travelled up and down and over smooth and rough; But there’s not a surface equal to the old blackstuff!Yosser, played by Barry Sloane, has become famous for the way he articulates his manic desperation to find a job, any job: “Gizza job. Go on, gizzit, go ‘head, giz it if you’ve got it, I can do it. Giz it then. Go ‘head, gizza job.”

That’s easy enough to understand, but I have to confess that for someone attuned to received pronunciation that was once used on BBC World Service, especially if you were brought up as a child in India, the Scouser accent is sometimes a little difficult to follow. But that is entirely my failing. However, after a while, you get the hang of what’s going on.

The men are all on the dole, but the department of employment uses spies – “sniffers” – to try to find out if the men are moonlighting by doing cash-in-hand jobs on construction sites while signed on for unemployment benefits.

Miss Sutcliffe (Helen Carter), supervisor at the department of employment, has some good bits of dialogue.

She tells Moss, one of her “sniffers”: “Don’t look so worried, Mr Moss. Unemployment is a growth industry. So much so that here, they’re expanding. New premises, more staff. Which means as it happens… I think I do have a job for you. There’s a particular group we’ve been keeping tabs on. All in and around Liverpool 8.”

She is referring, of course, to alleged fraud by the famous five.

She does provide valuable insights. She tells Dixie (Mark Womack) who moonlights as a security guard: “It can be very emasculating, when a husband isn’t bringing home any money, but the wife is.”

Uneployment, which had reached three million in 1982, was seen a reflection of the harsh economic policies pursued by Margaret Thatcher, then prime minister. Work had dried up in the Liverpool docks, just as Brexit has shrunk the British economy.

On the way to see the play – it was a coincidence – but I bumped into the artist Chila Burman, who was born and brought up in Liverpool. Her father had arrived in the city from India in 1954 and taken up selling ice cream from a van with a model of a tiger on top. This is a motif his daughter has adopted in her art work. But perhaps the Liverpool in which Chila grew up, was relatively stable compared with the 1980s. Gorge Malone (played by Philip Whitchurch) is in his 70s, much older than the other four and acts as a sort of father figure.

Chrissie, played by Nathan McMullen, is berated by his wife, Angie, for feeding the last three slices of bread to his geese. Lauren O’Neil multi-tasks as Angie, as well a number of other characters.

At one point, Chrissie talks to his birds about his wife’s fury: “Yeah, well, it’s your fault. I shouldn’t have given you that bread. The last three slices. I know that. But they were stale. You don’t mind stale, do yer. How much guilt can I take, ey? Where do you go from bread? Bread winner? That’s what she’s really saying, isn’t it. I’m the bread winner or meant to be. The provider.”

Like the others, he is now unable to provide for his wife and children.

His wife gives him the silent treatment: “The main problem with the silent treatment, of course, is that its effectiveness as a weapon of war stems from the fact that the victim is unable to ascertain what exactly he’s done to bleedin’ merit it.”

Angie responds: “What’s the point, gas has gone, can’t cook anything anyway if there was anything in the fridge, which there isn’t. Until they come and cut that off.”

Chrissie says: “I’ve never had a life outside of you and Justine and Clare. That’s all.”

In the end, Chrissie, who happens to have a gun, turns it on his birds. Joblessness has stripped him and the others of their dignity.

He addresses his wife: “What do you think it’s like. For me. Ey? A second-class citizen. A second-rate man. With no money and no job…”

It’s not that his wife doesn’t understand, but she responds: “Tell it to be kids, Chrissie. Tell it the cupboards and fridge. See how full your words can make them. And when you do, you can make breakfast, and then you will have found a job. You’ll have become a frigging magician.”

George Malone drops dead of natural causes, but he is predeceased by his son, Snowy, who falls to his death while attempting to escape “sniffers”.

Before he dies in his wheelchair, George can remember happier times: “Forty-seven years ago, I stood here. A young bull. And watched my first ship come in… They say memories live longer than dreams, those dreams of long ago, they still give me hope. And faith, in my class. I can’t believe there’s no hope…”

Yosser, meanwhile, who has been driven to the edge, defines himself as “a man with no job”.

“I want to be noticed, Chrissie, I want to be someone, I want to be seen,” he rages in anguish. “I am a human being! I’m alive, I’m here now, look at me!”

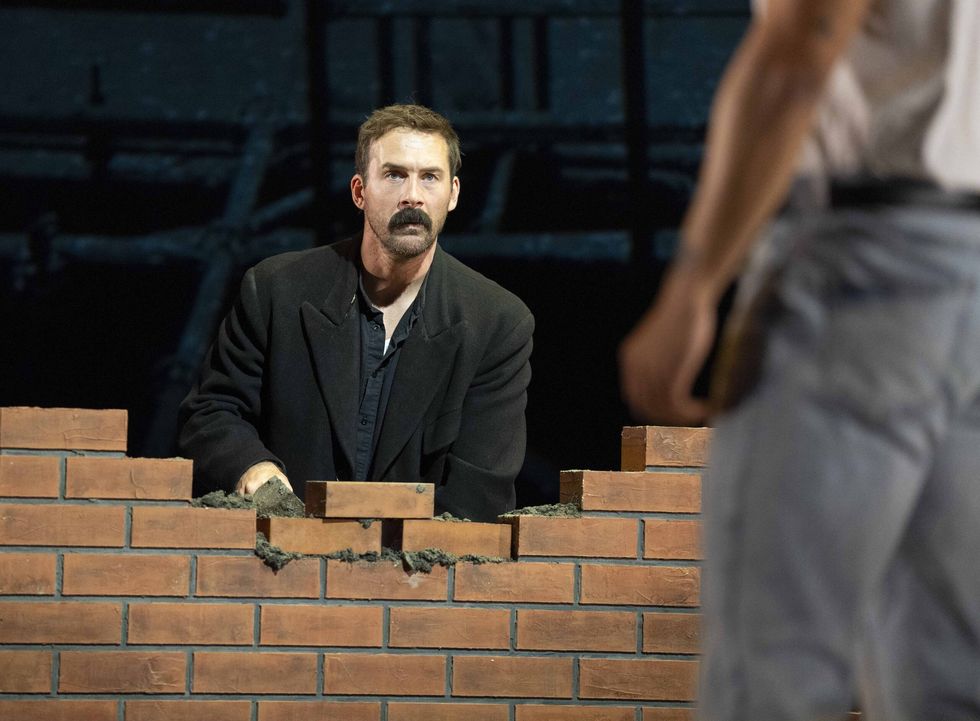

Asked to lay some bricks, he messes up the job and is fired since he most certainly does not have the skills of a bricklayer.

But he pursues, in turn, a groundkeeper, a milkman, a lollipop lady and even a priest, with his appeal, “I could do that. Ah giz a job.” He holds imaginary conversations with his children even though they have been taken away by his wife who has abandoned him. After he headbutts a bailiff, the police have to be sent in to make a violent arrest.

It is hard not to compare the setting of the play with today’s politics of unemployment. According to UK labour market statistics lodged with the House of Commons Library, in March this year, 1.49 million people aged above 16 were unemployed. What is particularly significant is that 9.38 million people aged 16-64 were economically inactive, reflecting systemic issues and ongoing challenges in the job market.

The number of vacancies fell in the last quarter and over the year to 898,000 in February to April 2024, but it remains above preacademic levels. According to opposing point of view, many prefer either not to work because the welfare benefits are relatively generous or have mental health problems left over from the pandemic.

n Boys from the Blackstuff is at the National until Saturday (8), then at the Garrick Theatre in London from next Thursday (13) until August 3.

Neetika Knight

www.easterneye.biz

Neetika Knight

www.easterneye.biz

Raj Ghatak

Raj Ghatak

Isaac Newton’s birthplace, WoolsthorpeManor, Lincolnshire

Isaac Newton’s birthplace, WoolsthorpeManor, Lincolnshire

Women from the Happy Hour Project engaged in creative workshops

Women from the Happy Hour Project engaged in creative workshops