THE British Museum’s well-researched new exhibition, Ancient India: living traditions, from May 22-October 19, 2025, will have profound appeal for Hindus, Jains, and Buddhists in the UK.

Britain has more than a million Hindus, with the proportion born in this country – now probably 60–70 per cent – increasing year on year as the first generation fades away.

It is often said that Hinduism is not so much a religion as a way of life. The same can be said for Jainism and Buddhism. The latter was founded by Prince Gautama, who was called Buddha after he gained enlightenment. And from India, Buddhism spread to China, Japan and south-east Asia.

Today, there are around 30 million Indians, the majority of them Hindus, dispersed across the world. In Kenya, Uganda, South Africa and elsewhere on the African continent, the Hindu immigrants who left Gujarat, for example, kept their religion and even the caste system alive. Today, Diwali is celebrated in No 10, Downing Street and in the White House. The Hindujas, Britain’s premier business family, make a special effort with their high-profile Diwali parties.

The former prime minister, Rishi Sunak, born in Southampton to Punjabi Hindu parents who emigrated to Britain from Kenya, spoke of the concept of dharma (duty) in his interview with Eastern Eye on the eve of last year’s general election, and more recently with the BBC’s Nick Robinson. Rishi referred to Lord Krishna’s discourse with Arjuna in the Mahabharat, which forms the Bhagavad Gita.

“This is one of our religious scriptures,” Rishi said, recalling he had sworn his oath on the sacred Gita when he became an MP in 2015 and later a member of the Privy Council.

The British Museum’s exhibition, said to be the first of its kind, will feature more than 180 objects, including 2,000-year-old sculptures, vibrant paintings, drawings, and manuscripts. It will examine how India’s ancient indigenous religions moulded its sacred landscape and continue to influence spiritual and artistic traditions.

Curators collaborated with an advisory panel of practising Buddhists, Hindus and Jains. Also, out of respect for the sacred objects, conservators took off their shoes and socks while handling them.

“Between 200 BC and AD 600, artistic depictions of the gods and enlightened teachers of these three religions dramatically changed from symbolic to showing them as human figures, with the iconic imagery and attributes that we know today,” according to the museum.

“Hindu, Buddhist, and Jain sculptures were produced in the same workshops in artistic and religious centres such as the ancient city of Mathura, meaning there are many similarities in this religious art. Great temples and shrines across the subcontinent were cosmopolitan hubs, drawing pilgrims from across Asia and the Mediterranean, and spreading these ancient religions and their art.

“The exhibition underscores the deep cultural and spiritual impact of south Asian, east Asian, and southeast Asian diaspora communities in the UK.”

It will surprise most people to learn that for all her right-wing politics, the former home secretary Suella Braverman describes herself as a benign Buddhist. She took her oath of allegiance as an MP on the Buddhist Dhammapada.

Ruth Ellis, who in 1953 became the last woman to be hanged in Britain after being convicted of murder, was prosecuted by Christmas Humphreys, who later became a judge. He wrote a number of works on Mahayana Buddhism and in his day was the best-known British convert to Buddhism. And the Dalai Lama, the leader of the Tibetan Buddhists, has a huge international following, especially in Britain – and in Hollywood.

The exhibition’s curator, Sushma Jansari, said: “The show explores the origins of Hindu, Jain, and Buddhist art in the nature spirits of ancient India, through exceptional sculptures and other works of art. We also bring the story into the present: with almost two billion followers of these faiths globally, these sacred images hold deep contemporary relevance and resonance.”

She added: “From the first century AD onwards, Buddhist and Hindu devotional art gradually spread along sea-and-land-based trading networks to central Asia, east Asia and southeast Asia. Sacred imagery and religious ideas from India were adopted and adapted, merging with local beliefs and styles to produce unique depictions of Buddhist and Hindu deities and enlightened teachers.”

And Nicholas Cullinan, who left the National Portrait Gallery to become director of the British Museum, commented: “India’s sacred art has had a profound impact on its own cultural landscape and the broader global context. By bringing together centuries of devotional imagery and collaborating closely with our community partners, we not only celebrate the legacy of these faiths, but also recognise the ongoing influence of south Asian traditions here in the UK and worldwide. This exhibition is a testament to the vibrancy, resilience, and continued relevance of these living traditions.”

Hindus are quite familiar with the concept of the third sex or fluidity between the sexes. That runs counter to what US president Donald Trump declared in his inaugural address: “As of today it will henceforth be the official policy of the United States government there are only two genders, male and female.”

The exhibition includes a painting, from about 1790-1800, of Ardhanarishvara, “lord who is half woman”, with Shiva and Parvati combined in one deity. Shiva is shown on the left with the river Ganges flowing from his matted hair while he carries a trident and drum. His consort Parvati wears a crown and holds prayer beads. Other exhibits include the Bimaran casket from about 1st century. The Buddha was first represented symbolically, through footprints or a tree, for example, and was only later depicted in human form. This gold reliquary might represent the earliest dateable image of the Buddha shown as a man.

There is Gaja-Lakshmi (‘Elephant Lakshmi’) with yakshi (female nature spirit) origins. She bestows good fortune and is one of the most popular Hindu, Buddhist and Jain goddesses. The dark bodies of the elephants symbolise monsoon clouds filled with much-anticipated rain ready to bring the earth to life. There is a Ganesha made in Java from volcanic stone, from about AD 1000– 1200. There is also a sandstone figure of Ganesha, from about AD 750, found in Uttar Pradesh. Ganesha is the playful god of new beginnings, who both places and removes obstacles (Sunak kept a Ganesh on his desk at No 10).

There is also the head of a grimacing yaksha, about second or third century. “This mottled pink sandstone figure represents ayaksha (male nature spirit). Yakshas can grant prosperity, but also make life difficult if not properly placated.”

Another exhibit is a 17th century Naga, a “stone plaque with the rearing figure of a five-headed cobra. Today, across India, popular veneration of divine snakes by followers of different religions still centres on such devotional images.”

There is a marble figure of a seated Jain Tirthankara (Jain enlightened teacher) from about AD 1150-1200.

Worthy of attention is the silk watercolour painting from China of the Buddha, from AD 701–750. “From about the third century BC, following trading networks, Buddhist missionaries took their faith and its devotional art beyond India.”

Ancient India: living traditions is at the British Museum from May 22-October 19

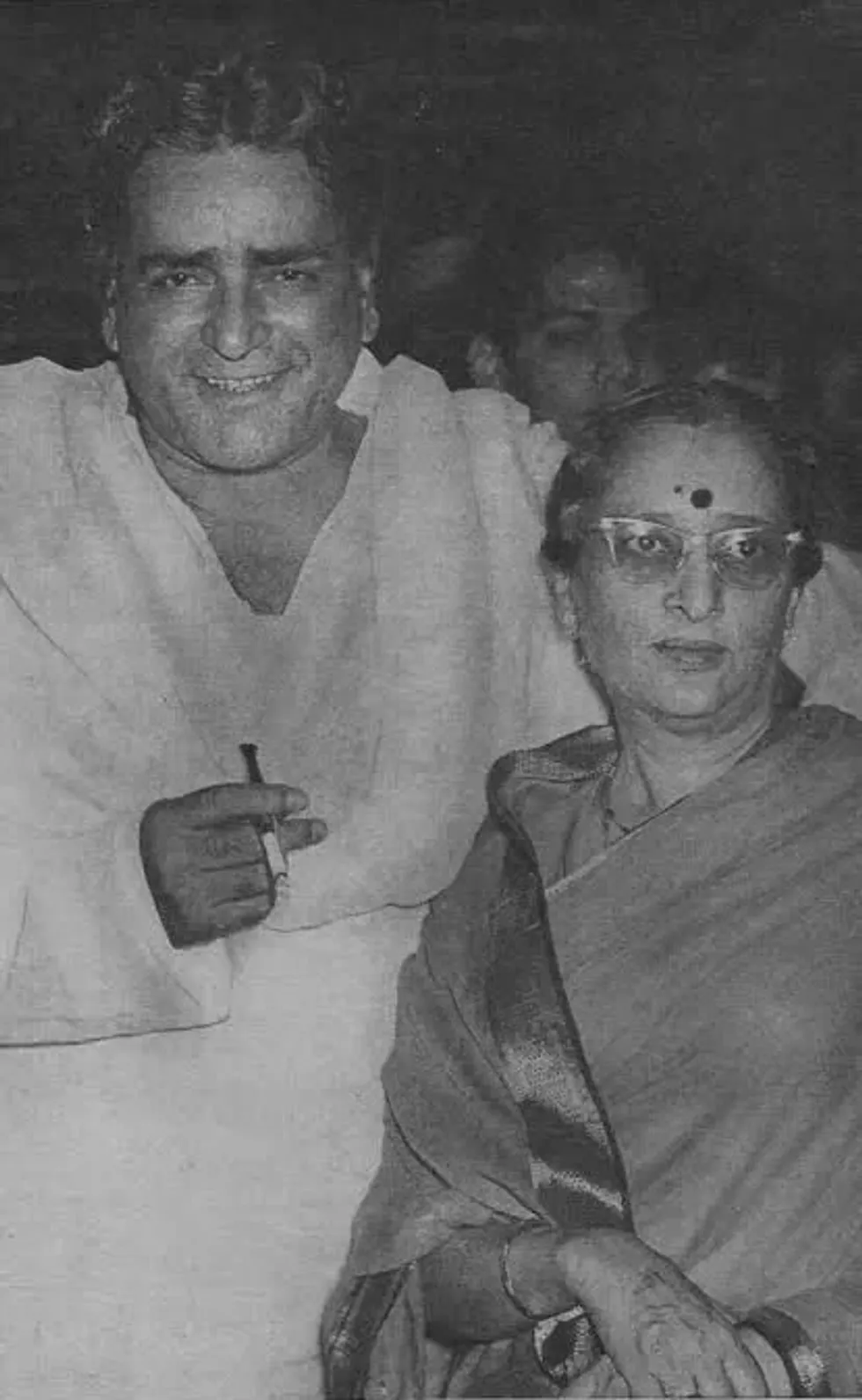

Prithviraj Kapoor and Ramsarni Mehra Reddit/ BollyBlindsNGossip

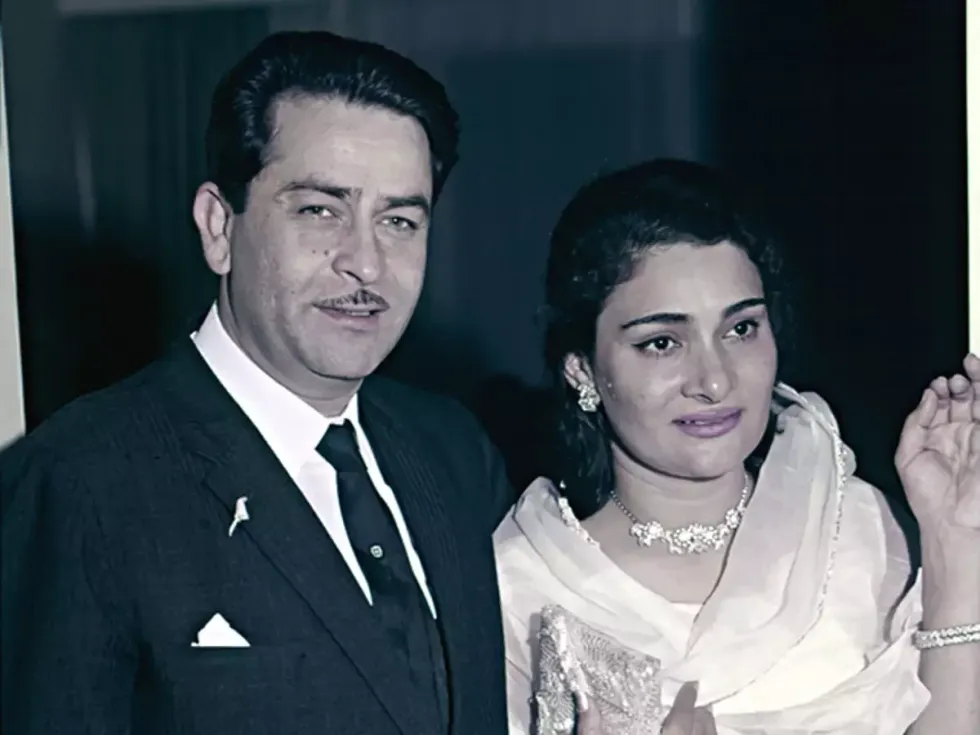

Prithviraj Kapoor and Ramsarni Mehra Reddit/ BollyBlindsNGossip Raj Kapoor and Krishna MalhotraABP

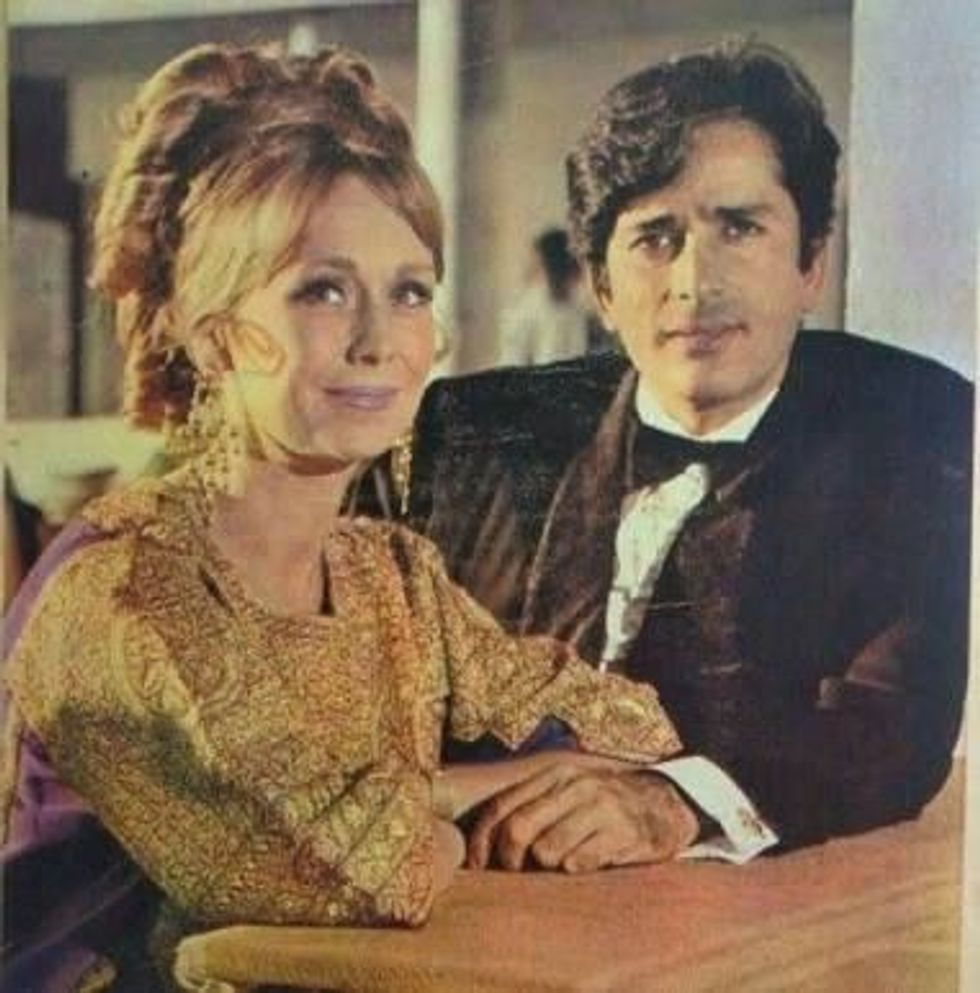

Raj Kapoor and Krishna MalhotraABP Geeta Bali and Shammi Kapoorapnaorg.com

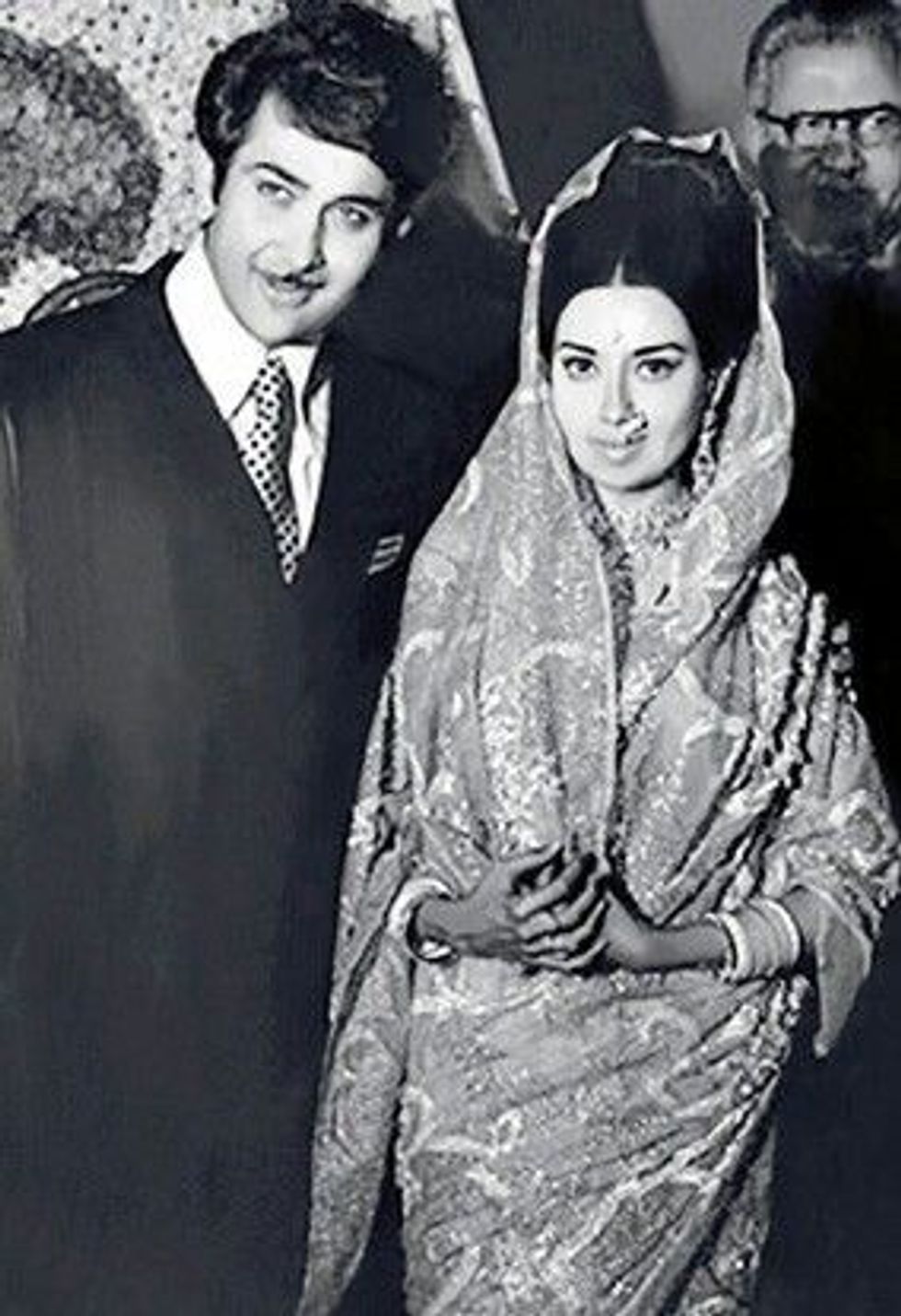

Geeta Bali and Shammi Kapoorapnaorg.com Jennifer Kendal and Shashi KapoorBollywoodShaadis

Jennifer Kendal and Shashi KapoorBollywoodShaadis Randhir Kapoor and Babita BollywoodShaadis

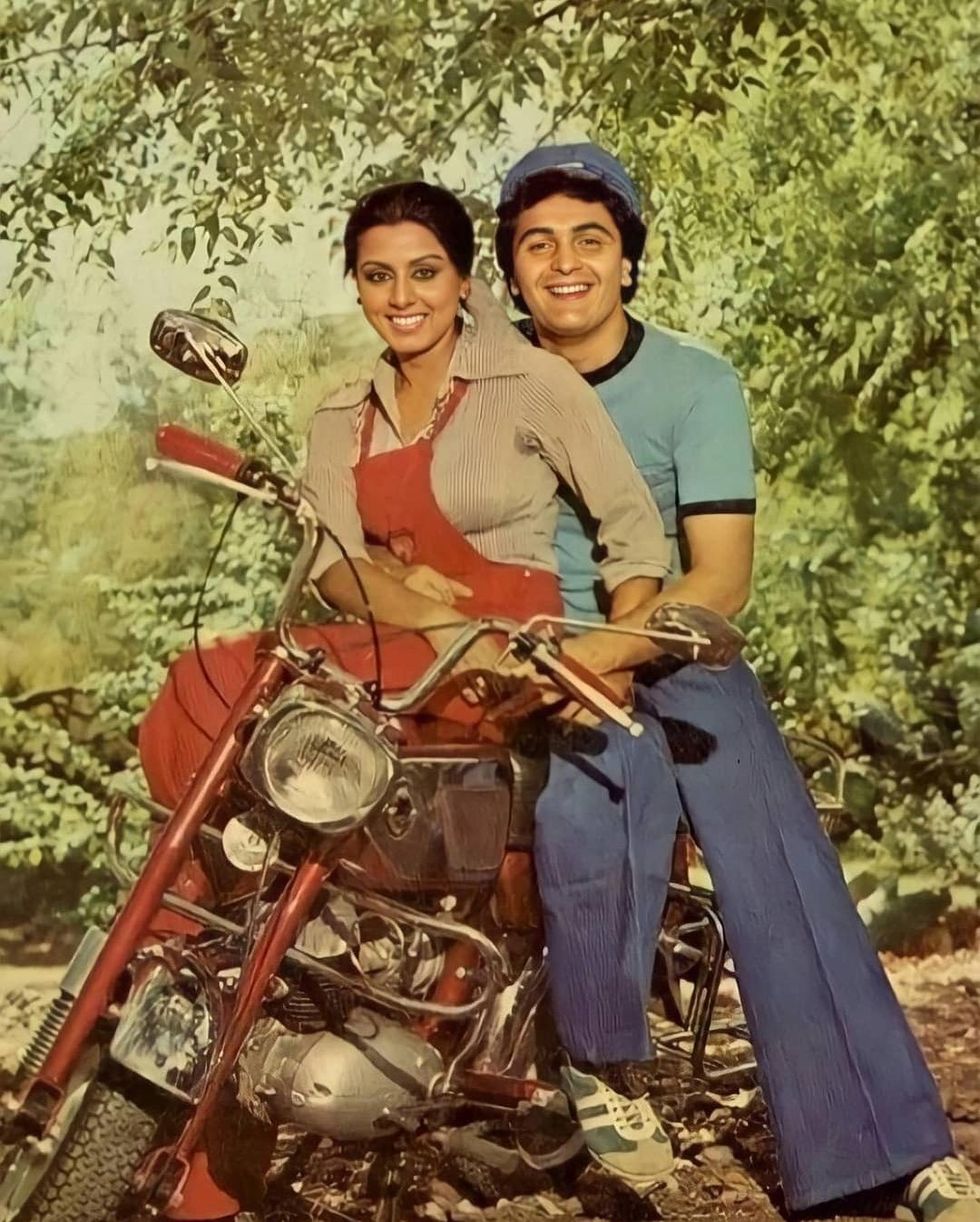

Randhir Kapoor and Babita BollywoodShaadis Neetu Singh and Rishi KapoorNews18

Neetu Singh and Rishi KapoorNews18 Rajiv Kapoor and Aarti Sabharwal Times Now Navbharat

Rajiv Kapoor and Aarti Sabharwal Times Now Navbharat Alia Bhatt and Ranbir KapooInstagram/ aliaabhatt

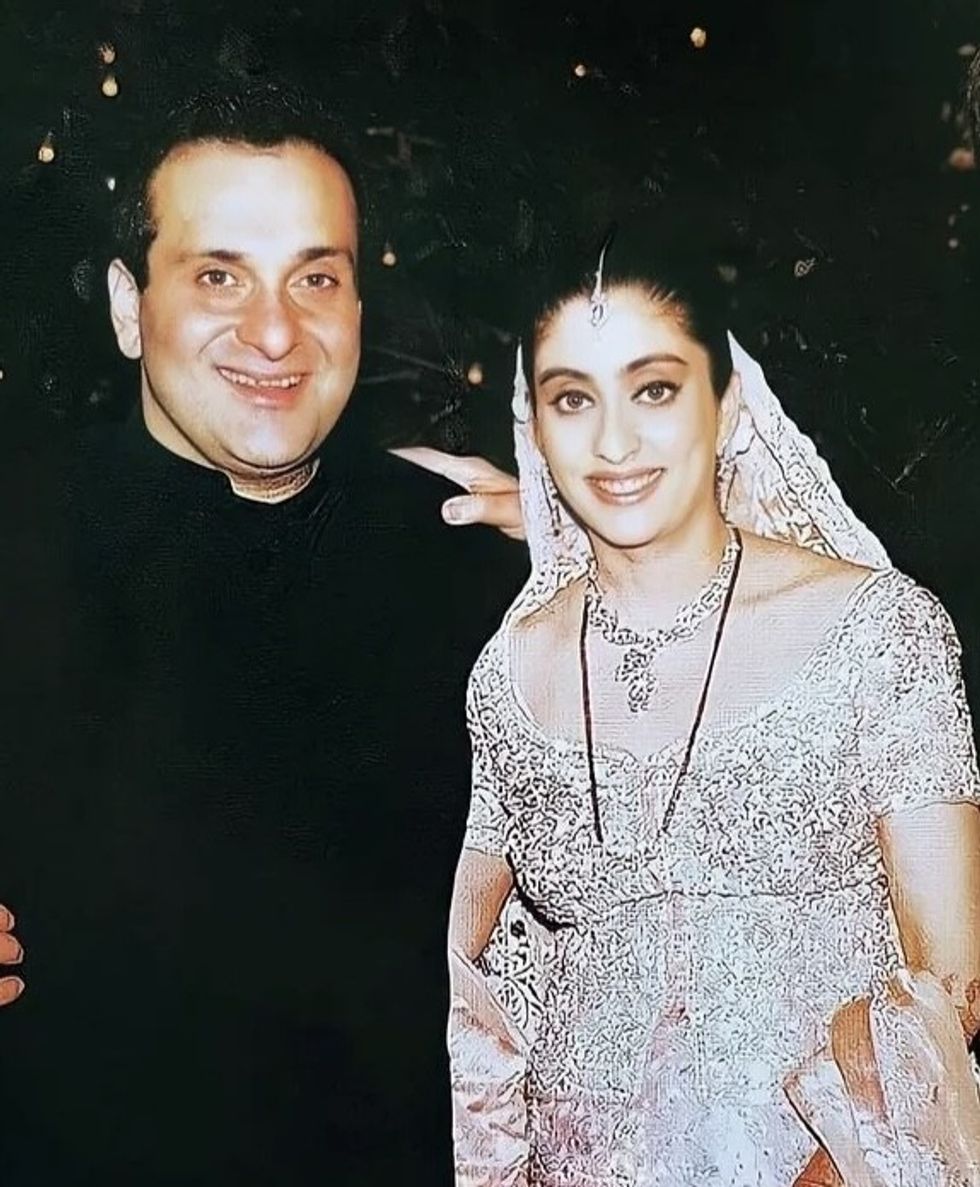

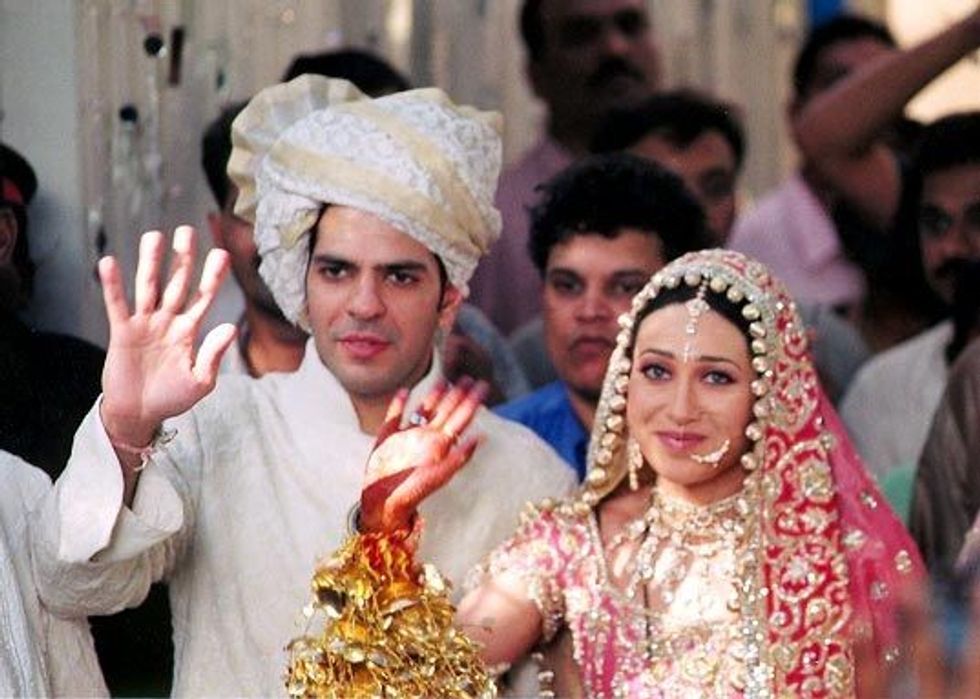

Alia Bhatt and Ranbir KapooInstagram/ aliaabhatt Sunjay Kapur and Karisma KapoorMoney Control

Sunjay Kapur and Karisma KapoorMoney Control

The real Aurangzeb, the sixth Mughal emperor

The real Aurangzeb, the sixth Mughal emperor Protesters burn a poster of Aurangzeb demanding the removal of his tomb in Nagpur in March

Protesters burn a poster of Aurangzeb demanding the removal of his tomb in Nagpur in March Akshaye Khanna as Aurangzeb

Akshaye Khanna as Aurangzeb Raj Thackeray

Raj Thackeray

With actor Kanwar Dhillon in 'Ram Bhavan'Instagram/ rahultewary

With actor Kanwar Dhillon in 'Ram Bhavan'Instagram/ rahultewary Udne Ki AashaScreen Grab 'Udne Ki Aasha'

Udne Ki AashaScreen Grab 'Udne Ki Aasha'

Mrunal Thakur in Sita Ramam

Mrunal Thakur in Sita Ramam  Director Anjali Menon

Director Anjali Menon Actress Nayanthara

Actress Nayanthara