By Amit Roy

IN A ROLL OF THE DICE (Linen Press; £9.99), Mona Dash explains the consequences of passing on faulty genes to her two sons and why she has relied continually on her faith and recital of the Hindu Maha Mrutyunjaya mantra (religious chant).

As the book’s subtitle makes clear, hers is “a story of loss, love and genetics”.

For good reason, it is commanded by two well-known authors. Neel Mukherjee has said, “It’ll go straight to your heart”, while Bidisha calls it “powerful, important and fearlessly honest”.

Mona, who comes from Odisha in eastern India, now lives in London where she works in software sales for a global technology company. She has dedicated her “memoirs” to her husband Kaustubh, and her two sons.

The first, Akshyat, was born in Kolkata on October 22, 1999, but died, aged eight months, on June 22, 2000, after inheriting a faulty gene, known as SCID – severe combined immunodeficiency – from his mother. His parents discovered too late that his white blood cells were unable to fight infection.

Since Mona was working for a UK company, she and her husband were able to move to London in March 2001, where her second son, Krish, was born prematurely on February 8, 2007.

He, too, was born with the same defective gene. But because the disease was caught immediately after birth, he was transferred urgently to the Great Ormond Street Hospital (GOSH) for children, where “the tiniest baby we had seen” came under the care of Bobby Gaspar, professor of paediatrics and immunology.

Thanks to a transplant of vitally needed bone marrow from his father – which Krish received at six weeks- he is today a normal healthy 12-year-old. An enthusiastic cricketer, he was present at his mother’s book launch at Waterstones Islington last week, where he announced: “I would like to be a fast bowler like Jofra Archer.” Watched by his parents and the doctor who saved his life, he gave an impressive demonstration of his bowling action.

Gaspar, who has written the introduction to the book, says he wants all 800,000 babies born annually in the UK to be tested for SCID as a matter of routine. It is a very rare disease, affecting 15 to 20 babies a year, but if not caught early, it can prove a death sentence.

Mona said she wrote the book, which begins with an account of the death of her first son, “to give hope, inspire others and create awareness of the disease in case it can help somebody.

“The only treatment is a bone marrow transplant.

“Somebody read the book and said, ‘I feel sorry for you.’ I said, ‘You don’t need to because I have gone through so much. It made me a different person. It has shaped me very well. And I am a strong believer. There was a lot of praying that I did. All the stuff from the ‘Gita’ and ‘Maha Mrutyunjaya Mantra’. All that really helped – and, of course, medical care.”

That side of Mona’s story was taken up by Gaspar, who “spends 40 per cent of his time seeing patients in the hospital and 60 per cent in the laboratory developing gene therapy treatments for complex diseases of the immune system”.

This is what he told Eastern Eye: “To fight any infection, your body has special white cells in the bloodstream. Those white cells grow from your bone marrow and the growth of those cells is governed or determined by specific genes. There are certain diseases, where because a gene is missing or a gene does not work, those white cells don’t grow and those white cells don’t function.

“And that is essentially what SCID is – a condition where a gene is missing and the white cells don’t grow.

“What happens in the first few months is the mother passes on through breast milk some protection, some antibodies. That protects the baby for a few months. When that fades in normal children, they will start to make their own. And they will have their own immune function.

“In a normal baby, the white cells will kick into action and get rid of that cough or cold, that virus. A baby with SCID can’t do that. So, when the mother’s protection goes, the baby has got nothing to protect it. Even the most common infection can be fatal.

“Usually what happens is they get an infection, they go in and out of the hospital, or see their general practitioner. They are put on medicines, but they can’t fight the infection properly. And because they don’t have any white cells and usually the parents don’t know anything about it- it is devastating when it happens.

“A lot of doctors will not have seen the disease. They think it is just like a normal infection. By the time they get to make the diagnosis, it may be too late.

“Sometimes the first time we see these babies are when they are on intensive care. And it is too late to be able to do anything.

“The best way to diagnose them – and this is something we have been campaigning for – is that all babies should be tested for this condition. If you can diagnose the condition at birth, you can protect the children and institute some treatment quite quickly.

“We do nationally screen for certain conditions at birth, but not this. In the US they are now starting to screen for it; in Germany, they are going to screen for it, and we are campaigning to screen for it in the UK as well. It’s a cheap test – a couple of pounds per baby.

“We know if you leave children undiagnosed, then roughly half or more of the children will die from the disease. If you screen them and treat them before they get an infection, then you have got over 90 per cent survival. So you can save all these children as a result of diagnosing them at birth.

“The cells arise from the bone marrow. And what we do is to give the children new bone marrow – somebody else’s bone marrow that can grow in their immune system. That works best when the children are in good shape.

“That’s what happened with Krish – he had a one-off treatment and that will repair his immune system. Because of his brother who died from the condition, as soon as Krish was born, he was diagnosed. He also had SCID. So we then took bone marrow from his father and gave it to him. He had it when he was six weeks old.

“In some families, because of the history, you can diagnose second or third babies at birth but in many families, there is no history. Then it will be a child having a problem for the first time.

“That’s why we are campaigning to screen all babies.”

Dhatt with sons Jasvinder and Parminder

Dhatt with sons Jasvinder and Parminder Dhatt as a young soldier

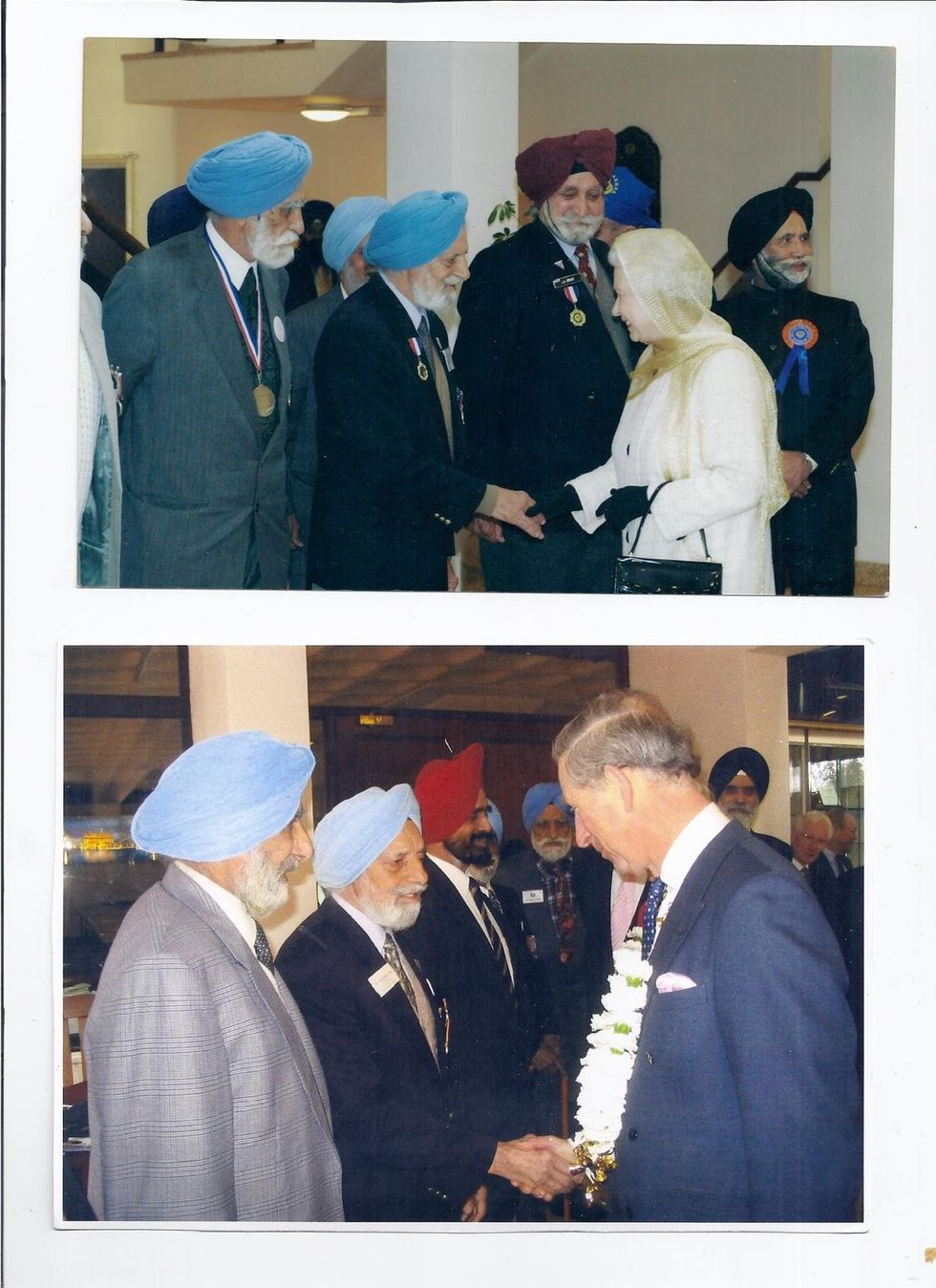

Dhatt as a young soldier Dhatt with the then Prince of Wales, and the late Queen

Dhatt with the then Prince of Wales, and the late Queen Dhatt gardening at home

Dhatt gardening at home Dhatt with his granddaughter Amrit

Dhatt with his granddaughter Amrit