IN HER novel, The Inheritance, Cauvery Madhavan writes beautifully, with lyrical descriptions of the Beara Peninsula in West Cork in Ireland.

Here, in the tiny village of Glengarriff, 29-year-old Marlo O’Sullivan has inherited a cottage high up in the rugged mountains. Along the nearby coastline around Bantry Bay, the fury of the heaving Atlantic often finds its way.

It is April 1986 and Marlo, who has arrived from London, is still reeling from the discovery that his sister is his mother. Hoping to make a fresh start, he takes in the breathtaking landscape as a local villager, called Dolores, gives him a lift.

“They were following the coast quite closely now, the road dropping steadily to sea level. The tide was coming in, filling up the rocky coves, pushing up gently against the mouths of rivers, creating eddies that swirled silently, and, in the crystal-clear waters of the shallows, fields of seaweed swayed, slapping the rocks to the rhythm of the current.

“All along to the left as they drove, a few houses, some new and proudly sporting green-fronted lawns, dotted the lush lower hills that were abundant with trees and wide untidy hedgerows that hid deep ditches. On the slopes above them, the contrast was stark. Ancient stone walling rose vertically up the mountains behind derelict farmhouses that were shrouded by gorse left unfettered. And even higher still, the mountains were treeless, with meagre layers of grassy soil smeared in the nooks of fantastical limestone folds.

“They drove past villages that were signposted but not to be seen, and as they rounded the tiny cove at Coomhola, he was surprised to see a small flock of swans bobbing in the sea.

“Dolores smiled. ‘There’s a good more than swan around here that’ll have ye wondering. It’s a different world altogether is Beara.’

“Marlo nodded. ‘And d’you know what, Dolores? I think I’m going to love it.’”

When a neighbour dies unexpectedly, Marlo takes over as the driver of his minibus service to Cork. He befriends Kitty, whose six-year-old son, Sully, cannot speak. The child rides the bus backwards and forwards, with the passengers keeping a kindly eye on him, allowing his mother to work.

Into the contemporary tale, Madhavan has woven in historical events from 400 years ago when English soldiers massacred an Irish clan led by Donald Cam O’Sullivan Beare on Dursey Island in 1602.

Madhavan, in fact, owns the 200-yearold cottage in Glengarriff, where she wrote The Inheritance. The novel is dedicated to “Beara and all who belong there”.

The Inheritance, which paints a portrait of life in a small Irish village (with no Asian characters), is a novel of exceptional charm.

When she began writing The Inheritance, there was a huge controversy about a novel called American Dirt by Jeanine Cummins about the Mexican immigrant experience, Madhavan said.

The debate was about “who is allowed to write whose story”.

As she hesitated about whether she was equipped to write an Irish story, her son lost patience with his mother and told her to get on with it.

Madhavan has clearly soaked up the Irish culture. She told Eastern Eye: “A good few people said to me, ‘We can’t believe this was written by somebody who is not native Irish.”

Madhavan and her husband, a vascular surgeon, live with their three children in Straffan, a “really tiny” village in County Kildare situated on the banks of the River Liffey, 25 km upstream of Dublin.

Her novel has been published in the UK by HopeRoad, which was founded in 2010 by Rosemarie Hudson, who wanted to find new authors with Asian, African and Caribbean heritage. Last year, it entered into a partnership with Peepal Tree Press, a Leeds-based publisher with a similar ethos.

Madhavan’s debut novel, Paddy Indian, came out in 2001, followed by The Uncoupling in 2003, and The Tainted in 2020. She is currently writing a fifth novel, a political one set in India between 1930 and 2010 (“I don’t intend to mince my words!”)

The Inheritance is set in 1986, which happens to be the year when she and her husband, Prakash, a junior doctor, who had been married for six months, arrived in the small Irish town of Sligo from Chennai. They chose not to go to England, which insisted Indian doctors first had to pass PLAB (Professional and Linguistic Assessments Board) tests.

“It was cheaper for us to go to Ireland,” she said. “It was a huge change. Sligo had 12,000 people and we were coming from Madras (renamed Chennai in 1996), which had, God knows, how many millions.”

About 25 years ago, she heard “a true story about a family that had a child who went on a bus to give them respite. I parked it away in my brain, thinking I am going to write a short story about it. Only in the last four or five years did I start thinking of it as maybe a novel. And about 23 years ago, we bought this small cottage in Glengarriff. Out cottage is not coastal, but three miles inland and we are on top of a mountain overlooking a forest.”

She recalls: “When I was three chapters into writing the book, I discovered the ridge where our cottage is, would have seen all the action I have described from the past. To the left of the ridge was where the English were camped and to the right is where the Irish were hiding in the forest. That location was witness to history. That spurred me on. I just felt the book was mine to write.”

The landscape is an important character in the novel, but Madhavan said: “I definitely didn’t think of the landscape being its own character in the book. That just happened. You can’t escape the landscape in Beara. Wherever you look, there is something incredible to see. Whether you’re looking towards the sea or the hills, the forest, or even if you’re just having a walk, either side of the path, you’ll see just amazing stuff.”

She said children being born out of wedlock “was a common thing in Ireland. Multiples of thousands of women gave up their babies. I can’t tell you how many people have written to me or told me, ‘That’s my story. I found out my mother was my sister or my aunt was my mother.’”

It is fortuitous that chance took her to Ireland. “As first-generation immigrants in Ireland, we had no family, like zero family. Something as simple as, ‘Can you go and pick up my child, I’m stuck in the dentist?’ or ‘My car’s broken down, my child is in school.’ You became so dependent on your neighbours. And then your neighbours became the family that you don’t have.

“And, so, for me, that Irish saying, ‘It is in each other’s shadow that people live,’ is the gospel truth. Probably one of the reasons we felt very much at home in Ireland is because it was so much like India.”

Her book

Her book

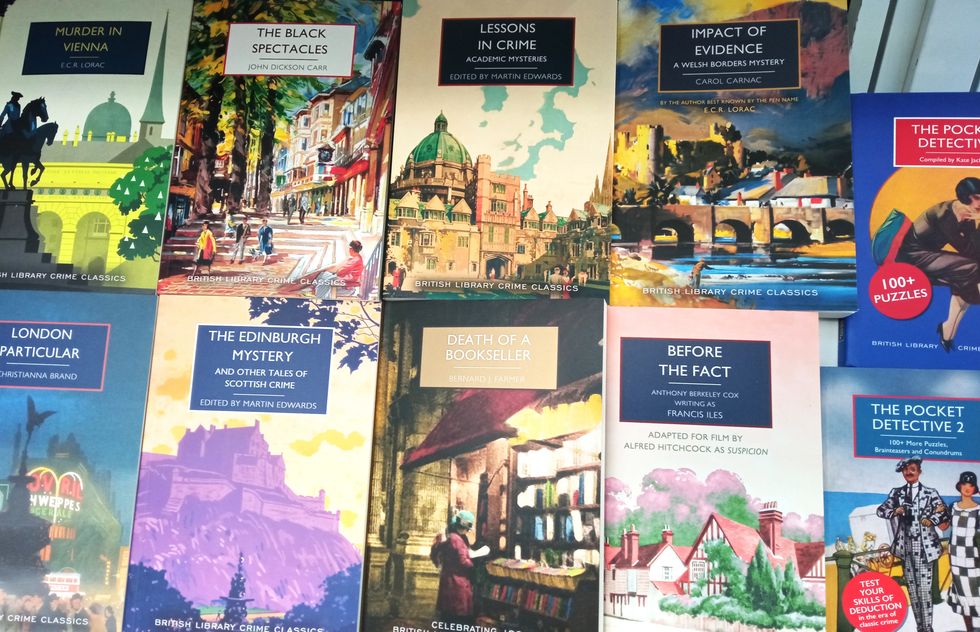

Some crime classics on display at the fair

Some crime classics on display at the fair

Genre: Young adult / FantasyAmazon.co.uk

Genre: Young adult / FantasyAmazon.co.uk Genre: Young adult / Fantasy / Historical FictionAmazon.co.uk

Genre: Young adult / Fantasy / Historical FictionAmazon.co.uk Genre: Young adult / FantasyAmazon.co.uk

Genre: Young adult / FantasyAmazon.co.uk Genre: Young adult / Fantasy / LGBTQ+Amazon.co.uk

Genre: Young adult / Fantasy / LGBTQ+Amazon.co.uk Genre: Young Adult / Contemporary / MysteryAmazon.co.uk

Genre: Young Adult / Contemporary / MysteryAmazon.co.uk Genre: Young adult / Mystery / ThrillerAmazon.co.uk

Genre: Young adult / Mystery / ThrillerAmazon.co.uk

The cover of her book

The cover of her book