WHETHER it is Rahat Fateh Ali Khan selling out big arenas, iconic festivals like Womad featuring qawwali concerts or compositions from major names like AR Rahman, Sufi music has been red hot in recent years.

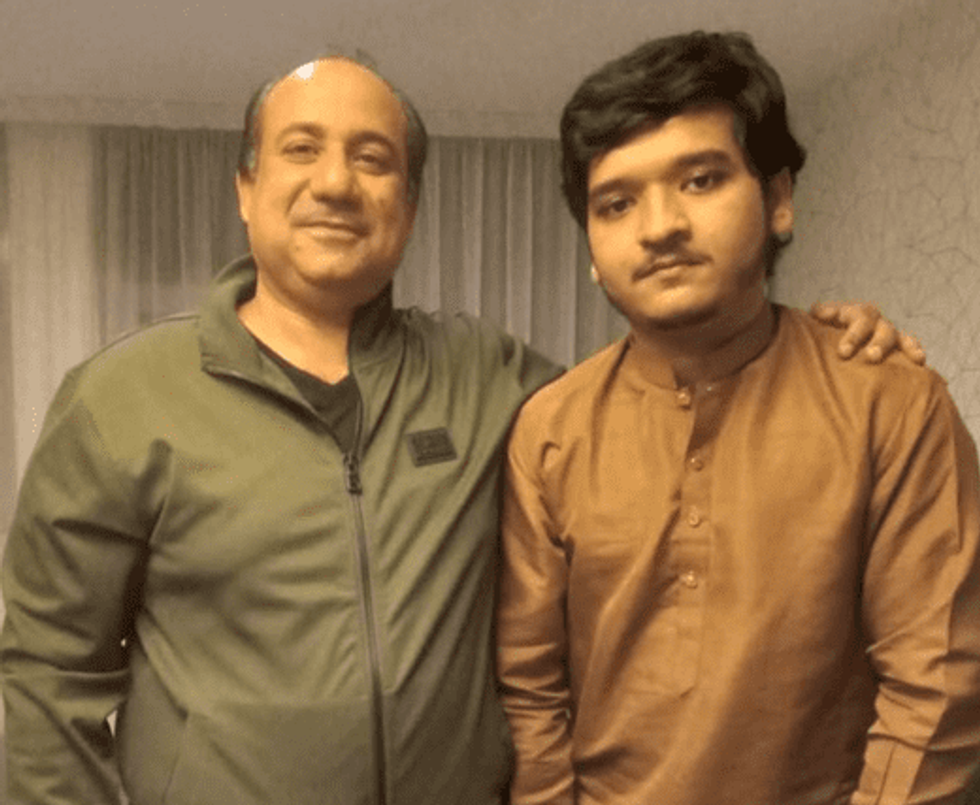

The next big breakout act in the devotional genre, rooted in over 700 years of tradition, is Chahat Mahmood Ali qawwal group. The supremely talented group from Pakistan recently arrived in the UK for a six month tour. The world-class nine-man act led by Chahat and Mahmood Ali will deliver their first major London show in Newham at Stratford Youth Zone, as part of South Asian Heritage Month on August 18.

Eastern Eye caught up with the fabulously talented father and son to discuss their fascinating journey, qawwali music, free London show, future hopes, and their music heroes.

How do you reflect on your journey?

Mahmood: This journey has been a blessing. I have worked with great artists, including Ustad Rahat Fateh Ali Khan, for 11 years, and Faiz Ali Faiz for five years. I have travelled to the UK, Europe, Japan, Morocco, Singapore, India and the US.

What has been your most memorable moment so far?

Mahmood: In 1999 till 2002, I joined Rahat Fateh Ali Khan’s qawwali team with a majority of (late) Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan group’s members. it was an honour to be on the second harmonium, while the late Ustad Farrukh Fateh Ali Khan (Rahat’s father) was on the first harmonium.

When did you discover your son had incredible talent?

Mahmood: Chahat was six years old when he started humming. I used to take him to concerts with Rahat saab and he would join in vocally.

What connected you to qawwali music?

Chahat: My forefathers have been in the singing profession for many generations. They had migrated from Jalandhar, India. I was surrounded by relations, who were active singers from Faisalabad, from day one. My uncle Haji Babar Hussain was a father-figure, and a member of Ustad Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan’s qawwali team. Nusrat saab hailed from our city Faisalabad and inspired me to pursue qawwali.

How do you feel being in a qawwali group with your father?

Chahat: My father is an experienced and exceptional artist, who has worked with many renowned qawwali groups, so being on my first UK tour with him is inspiring. He is a guide, mentor and someone who brings out the best in me daily. My younger brother Tameer Abbas is also with us - he plays tabla and is a versatile chorus singer.

What do you most love about your father as an artist?

Chahat: I love the way my father plays the lead harmonium. His vocals are amazing. He has a high pitch and very few can hit notes in qawwali like he does.

Tell us about your group?

Mahmood: The group is put together by our promoter Abid Iqbal. My son and I are blessed to have a great group of experienced artists backing us, who have played with lead qawwals like Rahat Fateh Ali Khan and Faiz Ali Faiz for prolonged periods. We have world-class artists Shahid Nadeem, Mohammed Nasir, Mohammed Kashif, Sarfraz Hussain, Sabir Hussain, Tameer Abbas, and Mohammed Rameez.

How do you feel performing shows in the UK?

Mahmood: I have always worked with sayarts.com, who are well connected promoters of qawwali. In the past, it was me as a musician, but now there is more responsibility as both me and Chahat are leading the group.

Chahat: UK helped put qawwali on the international map, so is very important. Some major artists have made a real name for themselves, thanks to the UK, which has a diverse mix of audiences, who value artists. Emerging artists do not get the same appreciation in Pakistan. If you have talent, then UK will push you higher.

What can we expect from your free concert in Newham on August 18?

Mahmood: You will get an energetic live performance of non-stop popular qawwali numbers, like Allah Hu, Tu Khuja Man Khuja, Mere Rashke Qamar, Bol Kaffara, Nit Khair Manga, Tumhey Dillagi, Mast Nazron Sey, Akhiyaan Udeek Diya, and Dam Mast Qalandar.

You are performing in London as part of South Asian Heritage Month. How important is your history to you?

Chahat: It’s very important and it is exactly why I want to connect young people to their roots, through my qawwali performances. Qawwali has connected people to their heritage for centuries and I want to continue flying that flag in a positive way. Mahmood: We are thankful to the honourable mayor Ms Rokhsana Fiaz for organising an event like this. We should all keep connected to our history, heritage, and roots. It is our duty to preserve our roots and why I have passed on what I’ve learned to my children. This has prevented a 700 year old genre from being wiped out.

Tell us about the strong connection you have to Rahat Fateh Ali Khan and his father?

Chahat: My father was a student of the late Farrukh Fateh Ali Khan (Rahat’s father), learning harmonium and qawwali singing from him. He was also part of Rahat saab’s qawwali group as a harmonium player for 11 years (1999-2010). I officially became Rahat saab’s student during his UK tour in July 2023.

Why do you think people love Sufi and qawwali music?

Chahat: Qawwali and Sufi music take audiences on a journey and help connect them to a higher power. It makes you feel something, even if you can’t fully understand the lyrics. It can purify your heart and has lyrics written by some of the greatest saints. It has a message of togetherness, peace, love and understanding.

What inspires you as an artist?

Mahmood: The late Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan showed the world his musical talent and put Pakistan onto the international map. He has also inspired a generation of artists, including us. Chahat: Audiences interacting with me during my performance and clapping along is so inspiring. I feed off their energy and feel motivated to give my best.

Who is your qawwali hero?

Mahmood: The late Ustad Farrukh Fateh Ali Khan for inspiring me. I learned so much from him. Chahat: My qawwali hero is Ustad Rahat Fateh Ali Khan, as he worked hard to create a name for himself. My father worked with Rahat for 11 years, so I have grown up admiring him since I was a young child.

Could you tell us the future plans for your group?

Chahat: We have signed with UK-based sayarts.com for the next 10 years. We want to take our music to the world from the UK. Like Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, we would like to collaborate with western artists, showcase our talent at international music festivals, as well as record

film music.

How does it feel like partnering up with leading British promoter Abid Iqbal?

Mahmood: I made my UK debut through sayarts.com with Rahat Fateh Ali Khan’s first UK tour in 2003. My son Chahat was a few months old then. I have stuck with Abid for over 20 years now, working with different Pakistani qawwali teams touring the UK. He has rewarded that loyalty by introducing my son Chahat. He has worked hard for the revival of qawwali music and always promoted new talent and given them the platform to break through.

Why should we all come and see you perform live?

Mahmood: Chahat Mahmood Ali is dedicated to developing new audiences in the UK and globally with a youthful voice of qawwali.

Why do you love music?

Mahmood: It’s food for our souls. Music has no language and connects the world. It enables us to gift great memories, travel the world and keep a centuries old tradition alive.

Chahat: Music is in my blood, and in my family. It is an important part of my heritage, history, and future.