THE British departed India when the country they had ruled more or less or 200 years became independent in 1947.

But what they left behind, especially in Calcutta (now called Kolkata), are their clubs. Then, as now, they remain a sanctuary for the city’s elite.

One evening, I am invited to dinner at the Bengal Club by a friend, Devdan Mitra, deputy editor of the Telegraph, an English-language newspaper. The club, the oldest in India, will celebrate its 200th anniversary in February 2027.

Devdan’s position as a member of the food sub-committee is an exalted one, for the Bengal Club prides itself on its culinary excellence. It has a reputation for its lobster thermidor, though I am happy with the grilled beckti.

The beckti, or barramundi fish, is known by many names around the world, including giant perch and Australian seabass.

“Our beckti is the fresh river variety, not sea beckti, which isn’t as nice,” says Devdan.

For dessert, I am persuaded to share a soufflé with him.

Once upon a time, Indians were not allowed into the club, as Lord Minto discovered when he invited Sir Rajendra Nath Mookerjee, a Bengali nobleman, to dinner in 1906. “But he’s my guest,” protested Minto when the doorman barred the Indian from entering the premises.

The doorman was not impressed that Minto was viceroy and governor-general of India (from November 1905 to November 1910).

“Rules are rules,” he said.

An embarrassed Minto promised his guest: “I will get you the land to start your own club where there will be no discrimination.”

In such a manner was the Calcutta Club born in 1907. Its first president was the Maharajah of Cooch Behar, Sir Nripendra Narayan. The Prince of Wales, later King Edward VIII, had lunch at the club on December 28, 1921.

Today, the club has a ‘Nirad C Chaudhuri corner’, housing rare books, paintings and awards that had once belonged to the eminent author who spent the last decades of his life in Oxford.

In fact, I actually rescued his belongings when they were about to be stolen and arranged for them to be shipped to the Calcutta Club after the author died in Oxford in 1999. But that is another story.

Meanwhile, in the dining room of the Bengal Club, the turbanned waiters were moving about like Jeeves. I asked Devdan about one of the several portraits of Englishmen that still hang in the club. It was that of Charles Metcalfe, the son of a major general who was the club’s second president and held the post for 11 years until 1838.

The Bengalis have decided not to take down the portraits of those who once lorded it over India.

“They are part of our history,” Devdan points out.

As I leave, I notice a marble plaque which says the Bengal Club had once been Lord Macaulay’s house. He had considered it to be “the best in Calcutta”.

I believe it’s the same (Thomas Babington) Macaulay who once boasted: “A single shelf of a good European library was worth the whole native literature of India and Arabia.”

Part of me wishes the British had settled in India and, in time, said the opposite of Rishi Sunak: “Of course, I am Indian.”

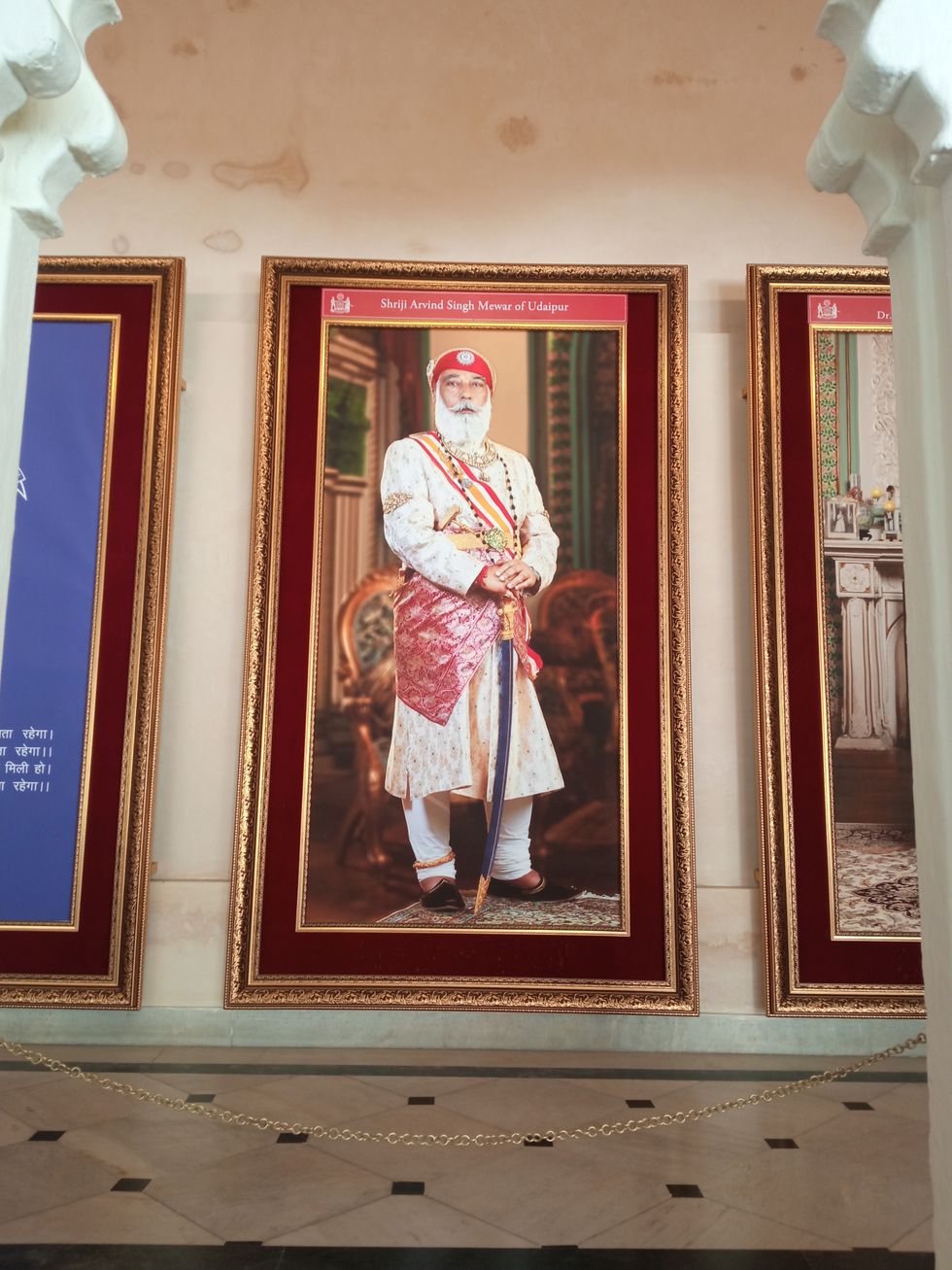

His portrait in the City Palace

His portrait in the City Palace

Pakistani artist Moazzam Ali Khan caught the attention of Bollywood legend Javed Akhtar with his soulful YouTube cover of Yeh Nain Deray Deray

Pakistani artist Moazzam Ali Khan caught the attention of Bollywood legend Javed Akhtar with his soulful YouTube cover of Yeh Nain Deray Deray John Abraham to headline action thriller Tehran

Getty Images for DIFF

John Abraham to headline action thriller Tehran

Getty Images for DIFF

Tikri Border, Haryana-Delhi by Aban Raza

Tikri Border, Haryana-Delhi by Aban Raza Harmz Matharu

Harmz Matharu Abhishek Bachchan in Be Happy

Abhishek Bachchan in Be Happy Devika's soulful vocals shine in her new Punjabi ballad Wisteria

Devika's soulful vocals shine in her new Punjabi ballad Wisteria Indian Idol star Nitin Kumar promises a soulful mix of qawwali, Sufi, and folk music at his upcoming UK performance

Indian Idol star Nitin Kumar promises a soulful mix of qawwali, Sufi, and folk music at his upcoming UK performance Kunal Kamra during his show

Wikipedia

Kunal Kamra during his show

Wikipedia

Swiss-Indian singer BombayMami is making waves with her bold style and sound

Swiss-Indian singer BombayMami is making waves with her bold style and sound Hania Aamir receives a questionable honour in London

Hania Aamir receives a questionable honour in London

A resident in Odessa, Ukraine, as smoke rises from a fire following a strike earlier this month amid the Russian invasion

A resident in Odessa, Ukraine, as smoke rises from a fire following a strike earlier this month amid the Russian invasion

Shweta Warrier

Shweta Warrier Harbans Singh Jandu

Harbans Singh Jandu Aamir Khan

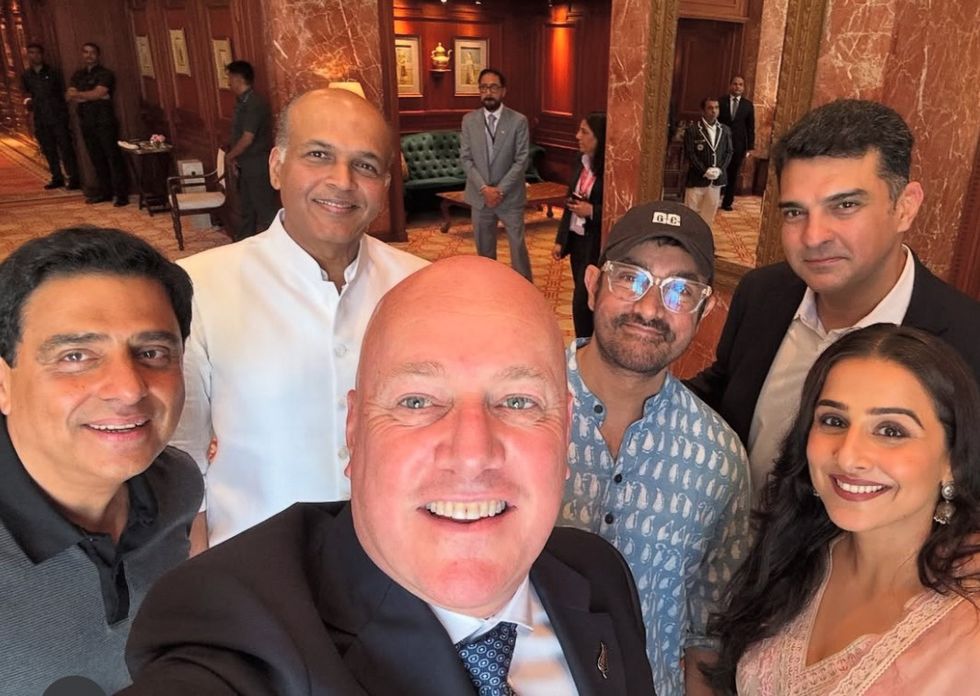

Aamir Khan Ronnie Screwvala, Ashutosh Gowariker, Christopher Luxon, Aamir Khan, Siddharth Roy Kapur and Vidya Balan

Ronnie Screwvala, Ashutosh Gowariker, Christopher Luxon, Aamir Khan, Siddharth Roy Kapur and Vidya Balan Madhuri Dixit

Madhuri Dixit

Anurag Bajpayee's Gradiant: The water company tackling a global crisis