RISHI SUNAK accelerated the inevitable defeat of his Conservative government by holding a summer rather than an autumn election, so this party conference season opens a new political era.

That election timing may change the immigration politics of this parliament too – but in different ways on the two headline issues of Channel crossings and the overall immigration numbers.

Sunak chose not to put his Rwanda plan to the test before the election, having little confidence that sending the first flights would actually stop the boats. Ironically, the same Channel crossings this summer – that would have undermined the deterrent case for Rwanda – are now being used to question prime minister Sir Keir Starmer’s decision to scrap the scheme instead.

Fewer people have noticed that Starmer is set to be the first prime minister for decades to oversee a significant fall in net migration numbers. Starmer has Sunak to thank for that too.

Net migration is set to halve under Starmer over the next 12 months, having trebled under Sunak. Exceptional spikes from arrivals from Ukraine and Hong Kong revert to the norm. Late changes to visa eligibility for the dependents of graduate students and care workers under the last government will mostly turn up in the statistics under its successor.

New reports this week on immigration attitudes, published by both British Future and More in Common, show how an increasingly polarised politics of immigration present distinct challenges to different leaders and political parties.

Research for British Future by Ipsos finds that 55 per cent of the public now support reductions in overall numbers. But seeing that actually happen will surprise most people. Just 12 per cent expect net migration to fall in the government’s first year in office – with most expecting current record levels to continue or rise further.

The general election saw a polarised immigration debate, reflected in a sharper partisan divide than before in public attitudes too. Views are more sceptical on the right and more liberal on the centre left. But most people are not thinking what Nigel Farage is saying on immigration. On every issue, the 14 per cent who voted Reform are more dramatic outliers from overall public opinion than the supporters of any other party.

That is because most people remain “balancers” on immigration – seeing both pressures from population change and gains for the economy and public services, while wanting to combine control and compassion on asylum too.

The Conservative leadership candidates have all agreed that the party lost trust on immigration. But why? Did the Tories just not take their promises seriously – or lack the competence to deliver? Or was there a more foundational problem of making promises that could not be kept?

The leadership candidates appear to think that it may be easier to promise once again in opposition what the party could not deliver in government, with the reality check of delivery deferred. They can suggest that the main problem with the Rwanda plan is that it has not yet been tried.

Current frontrunner Robert Jenrick says the old promise of “tens of thousands” should come back as a legal requirement to make sure it happens. Tom Tugendhat, Kemi Badenoch and James Cleverly seem more inclined to agree, rather than open up immigration arguments during a party leadership contest.

Yet, Tory voters see dilemmas of control. Most want the numbers to fall significantly; but when asked where cuts should fall, only a small minority of Conservatives want fewer visas in any area of work or study.

There are dangers for the party if the next leader focuses only on the votes lost to Reform. Though all parties struggle for public trust on immigration, it is striking how much the ‘balancer middle’ thinks Labour and the Liberal Democrats were closer to getting the balance right at the last election than Reform or the Conservatives. The Lib Dems quietly proposed a distinctly more liberal manifesto than Labour, yet the party found that no barrier to making 60 gains from the Conservatives.

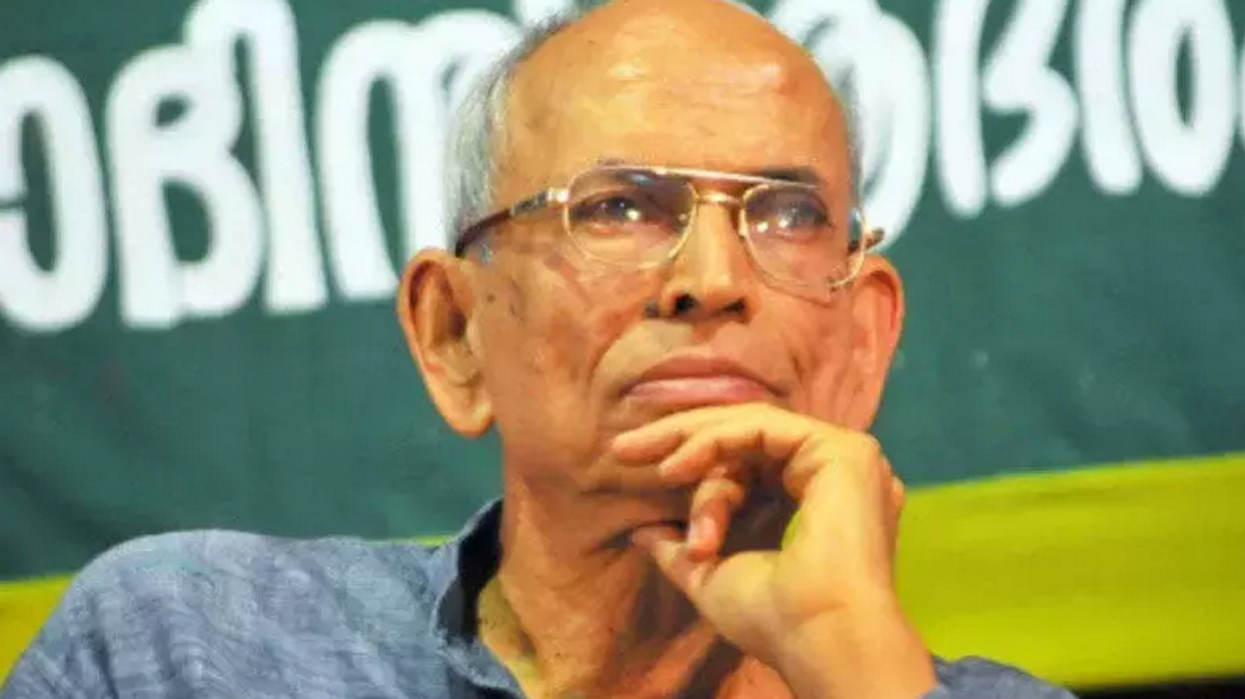

Sunder KatwalaStarmer’s challenge is how to separate the signal from the noise on immigration. One in five voters thinks immigration should be his top priority – that includes 55 per cent of Reform voters, but only six per cent of those who voted Labour.

The prime minister will face the most vocal pressure from the most anti-immigration quarter of the public that he has least chance of persuading. But a broad majority across those with liberal, balancer and more moderately sceptical views of immigration are more willing to give this government a hearing.

One challenge for Starmer and his home secretary, Yvette Cooper, is that they may often find the media will judge this government’s record against the tests of the Farage or Jenrick manifestos – just how low could the immigration numbers go, or how many international treaties is the government willing to quit?

If those are not Labour’s objectives, they need to use the breathing space of falling numbers by next spring to reset the debate.

(The author is the director of British Future)