By Sunder Katwala

Director, British Future

NEW mayors taking office across England this week - from the West Midlands and Greater Manchester to the West of England or Cambridge and Peterborough - will each face a distinct set of challenges and opportunities in the places they have been chosen to represent.

Yet, there is no city-region where the mayor could not make a significant difference to how people live together.

Integration happens, mostly, in the towns and cities where we live. So the new mayors could play a game-changing role on integration, ideally placed to implement integration strategies tailored to meet the needs of communities in their area.

A new report this week from British Future, backed by voices from across politics and civil society, calls for these mayors to appoint “deputy mayors for integration” to drive through an integration agenda at regional level.

Those agendas will each have their own distinct local flavour.

In the West Midlands that could include support for volunteering projects that bring diverse communities together, while in Cambridgeshire and Peterborough, the new mayor will need to address social and educational divides, particularly between Cambridge and the Fens.

The mayor of Greater Manchester could use new housing powers to help address geographic segregation of different faith and ethnic communities in areas such as Oldham and Rochdale; while in the Tees Valley their focus will be on addressing unemployment and underemployment, as well as ensuring that refugees and asylum-seekers are helped to integrate.

The West of England mayor will need to ensure there is housing to cope with a projected population growth, while in the Liverpool City Region they will be looking to ensure the city continues to attract new people, after years of population decline.

A local approach to integration, however, will only get us so far and as one poll closes, another will soon open. After a referendum that divided communities, party leaders Theresa May, Jeremy Corbyn and Tim Farron will need to set out, in their manifesto pitch to General Election voters, how their approach to integration would bring people together - including how they will respond to the challenges detailed in the recent report by Dame Louise Casey.

That should start with ensuring that everyone in the UK either speaks or is learning English. “Promoting English language is the single most important thing that we can do”, Dame Casey writes, echoing the consensus that a common language is an essential passport to full economic, social and democratic participation in our society. Yet, even with new government resources recently announced, significant gaps in funding and policy remain for those who want to learn English.

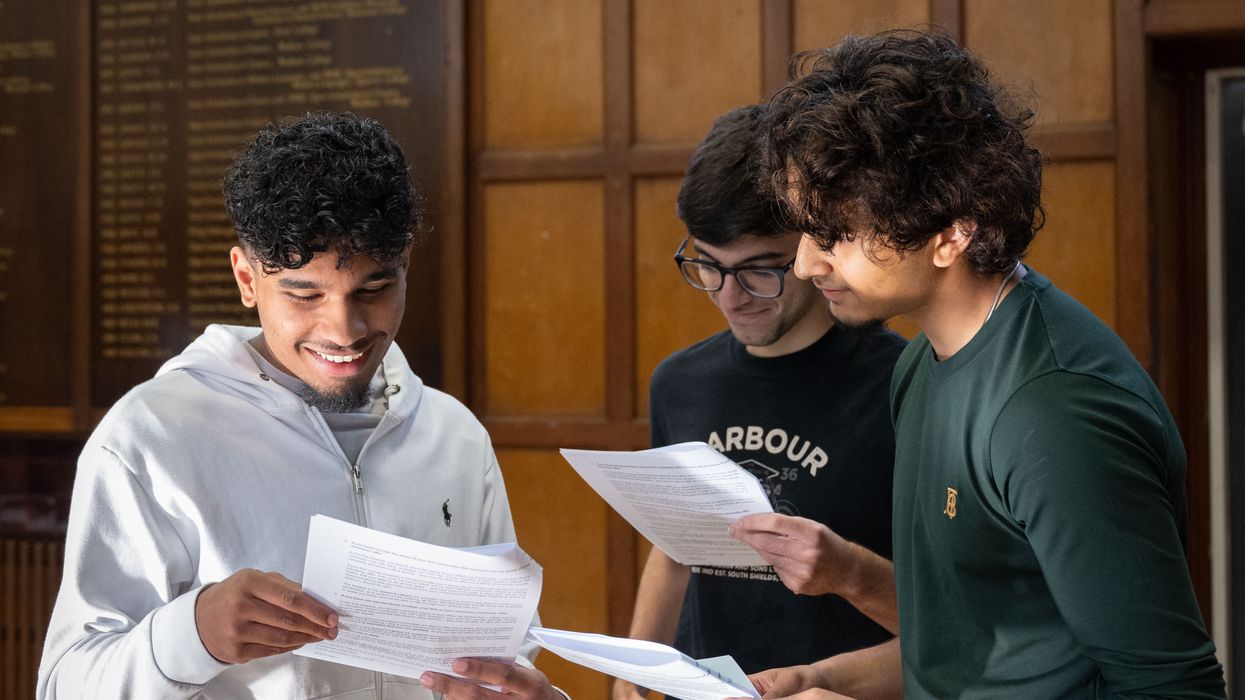

We also need to ensure that people can meet, mix and get to know each other better. That has to start in schools. No child should grow up without getting the chance to meet children from different ethnic, faith and class backgrounds to their own.

And once they leave school, people from minority backgrounds must have access to the same opportunities as everyone else. That is not the case right now: ethnic minority Britons are now more likely to be university graduates than their white British peers, but less likely to get an interview when they apply for a job. That is not only patently unfair; it undermines efforts to ensure that all citizens feel they have an equal stake and are equally valued across our society.

So we need national action from the top to tackle the things that divide us. But we must also do more to celebrate the things we have in common. That can be particularly effective at a local level, fostering a shared pride in a local identity; but it can work nationally too, including how we remember our history.

The story of the 1.5 million Indians, 400,000 of them Muslim, who fought for Britain in the First World War is a story of shared history that is still less-known than it should be.

Celebrating the things that are shared by all of us is so important because for integration to work, it must be an ‘all of us’ issue - not just something for migrants or ethnic minorities.

The divisions in our society are not, in any event, exclusively along the lines of faith or ethnicity: the EU referendum surprised many in its exposure of divides based on class, age, geography and educational achievement.

The new regional mayors will need to ensure their integration strategies feel relevant to all the citizens that they represent. And national politicians should do the same - setting out how their party would work to bring us together, as they seek the support of voters across Britain next month.

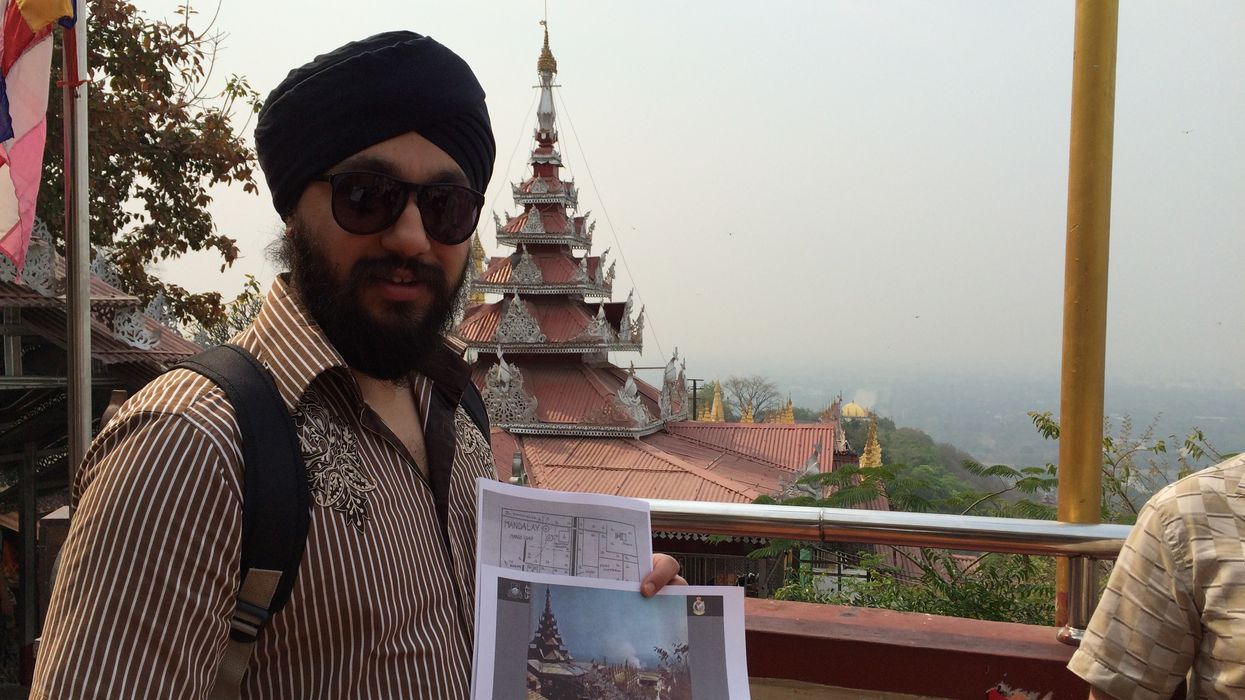

Peter Searle

Peter Searle

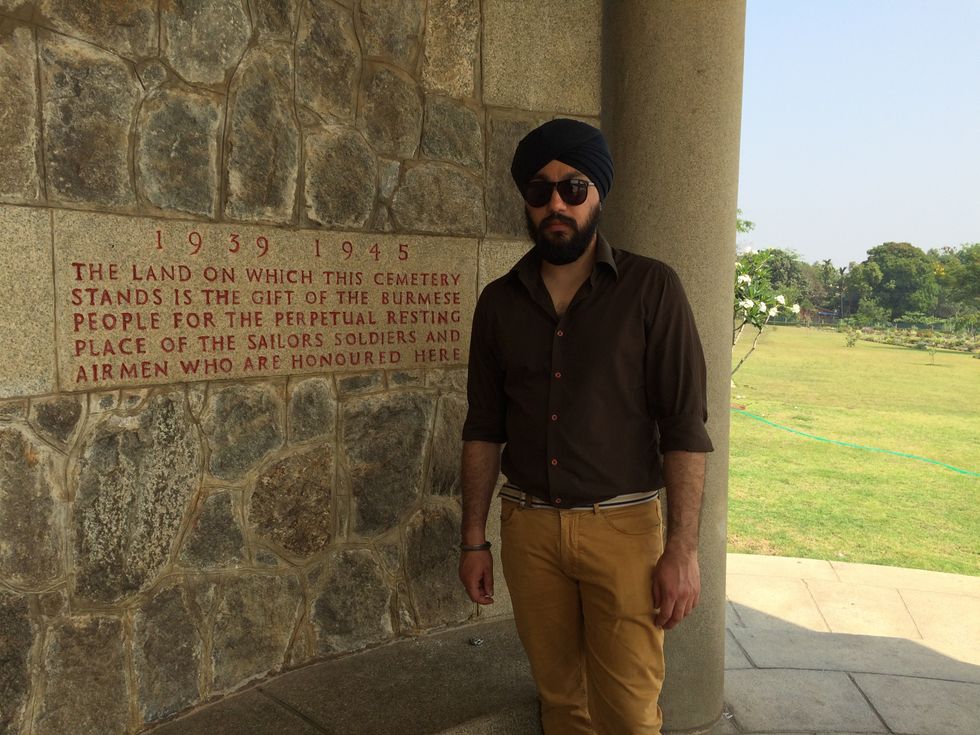

And, at Rangoon War Cemetery paying respects to those who fought to free Burma

And, at Rangoon War Cemetery paying respects to those who fought to free Burma

Minreet Kaur

Minreet Kaur

Comment: England’s new mayors could lead the way on integration