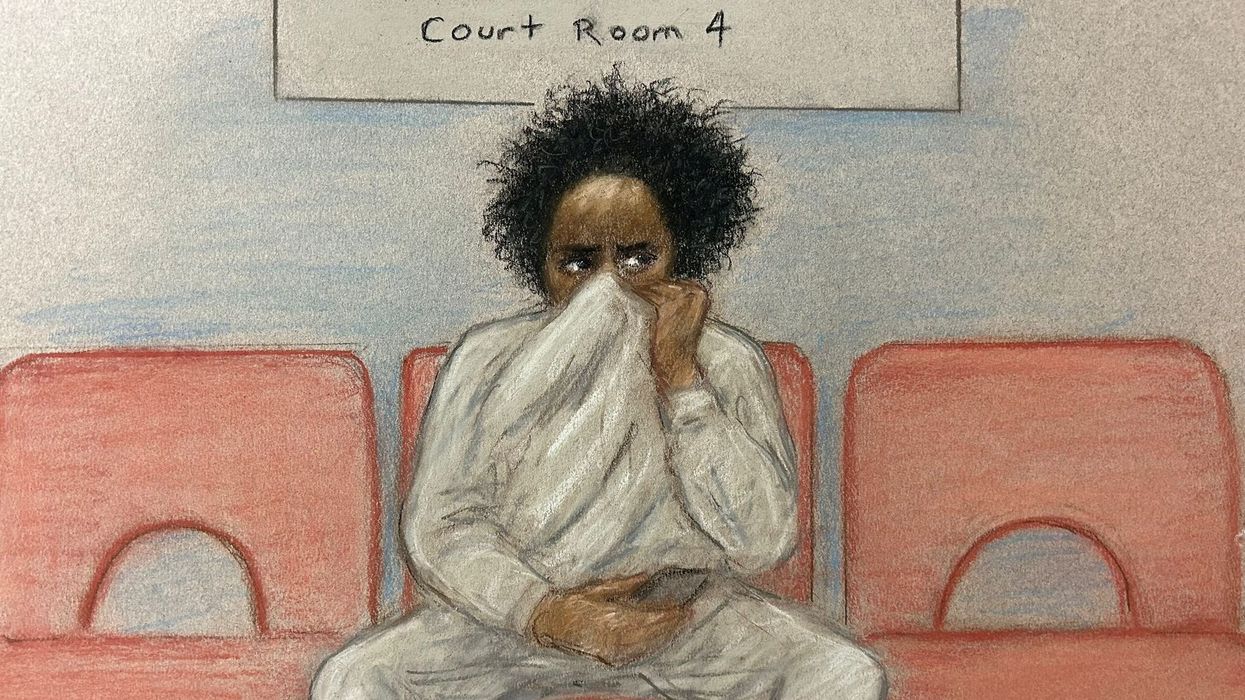

The guilty plea on the opening day of the Southport murder trial will save the parents of the three young girls who were murdered the ordeal of a full trial. It would have taken several weeks in court to prove in law the obvious, inescapable truth: that Axel Rudakubana had wielded the knife to commit these terrible crimes. Now a public inquiry must try to answer more difficult questions: why he did it, and how the murders could have been prevented.

When Rudakubana also was charged with terror offences - the possession of ricin and an Al-Qaeda manual - in October, it was widely assumed this confirmed an Islamist terrorist motive. With reporting restrictions lifted after the conviction, police and prosecutors have been unable to confirm that motive. They appear to believe the manual may have been in his possession more as a ‘how to’ guide to committing mayhem - along with much other material about school shootings and genocides - rather than reflecting specific sympathy to any cause.

Rudakubana was born in Wales in 2006, over a decade after the Rwandan genocide, after his parents came to Britain. How his family background and Rwanda’s history combined with other factors to influence his fixation with violence will be another question the inquiry must explore.

The perpetrator was referred to the Prevent programme three times, in 2019 and 2021. The prime minister, Sir Keir Starmer, called the judgment not to intervene on those occasions “clearly wrong”. Yet, in calling for future reforms, Starmer tacitly acknowledged that the issue may not have been with the decision in the specific case, but a gap in the policy design, over what the Prevent programme is for.

Every teacher has training on identifying those at risk of radicalisation, alongside other safeguarding responsibilities. The Prevent programme receives about 7000 referrals a year. The average age is sixteen. Boys aged between 11 and 14 years of age are the largest group. Because its focus is on extremism and terrorism, it takes forward fewer than one in ten of those cases. So, the most common decision given is “vulnerability present, but no ideological or counterterrorism risk”.

The problem is that, with Prevent focused on ideologies of extremism that can turn people into terrorists, there is no parallel programme of prevention for the growing numbers of people who could present a violent threat without any clear ideological commitment - because they fantasise about becoming notorious for a school shooting, or killing a celebrity, for example. With threadbare mental health services for young people, this appears to be an increasingly dangerous gap.

For all of the heated political controversy about Prevent over the last two decades, it has never been well understood by the general public. Indeed, research in 2021 by Crest Advisory found that two-thirds of people had never heard of the Prevent programme, including most people from Muslim and other minority backgrounds. This puts some of the polarised civic society and political debates into context. That Prevent is a voluntary programme would be counter-intuitive to most people, too.

The wider question of what inquiries are for has dominated the new year in Britain after a heated political argument over the harrowing history of ‘grooming gangs’. More needs to happen, locally and nationally, to secure confidence that misplaced cultural sensitivities will not prevent the law being applied without fear or favour across all citizens. It is important to be able to talk confidently about toxic sub-cultures of misogyny and abuse within British Pakistani communities, in order to support those working to shift the share of power and voice across genders and generations.

So, we do need to talk about cultural factors - within communities and institutions - in Asian communities, as we would do so when talking about the Irish community and the Catholic Church, and the struggles of the Church of England to get its house in order. That is an important foundation for being able to also challenge those relishing the opportunity for sweeping Pakistani-bashing caricatures promoting prejudice and discrimination in visa rules towards the entire group, or other efforts at racist radicalisation being dangerously promoted by the ill-informed billionaire troll Elon Musk.

The guilty pleas to ten counts of attempted murder are a reminder that several young lives were saved by heroic intervention in Southport. Southport’s tragedy remains the largest mass killing of children since the Dunblane school shooting in Scotland in 1996, when sixteen pupils and a teacher were murdered. From Dunblane’s grief and shock came what may stand out internationally as possibly the strongest ever example of a tragedy delivering lasting social change. There have been no school shootings in Britain this century - but over two hundred knife deaths per year. Southport’s tragedy last summer led not just to national grief - but to anger, conspiracies and racist riots. The challenge now is to seek a positive legacy from its pain too.

Sunder Katwala is the director of thinktank British Future

Shy Burhan

Shy Burhan  Dr Jamilla Hussain

Dr Jamilla Hussain A workshop funded by a Dying Matters grant

A workshop funded by a Dying Matters grant Rubina Khalid

Rubina Khalid