Rishi Sunak showed dignity and grace in defeat as he became a former prime minister this (5) morning. He told his constituency count in Richmond, Yorkshire, that he had conceded defeat during the early hours of the morning in a telephone call to Labour leader Sir Keir Starmer, speaking of the value of a democracy where “power will change hands peacefully with goodwill on all sides”.

This was Sunak as Britain’s anti-Trump – expressing sentiments of democratic civility that we would hope to take for granted in Britain, in stark contrast to the disruption of democratic norms after the last US presidential election, and perhaps to some of the most polarised arguments over Brexit here, too. Speaking outside Downing Street, Sunak praised his political opponent as “a decent public-spirited man who I respect”.

In his resignation speech, Sunak focused first on apologising – to the country and to his party – and taking personal responsibility. He briefly spoke of what he had been proud of during his short two-year half-term as prime minister.

Sunak did then acknowledge his role as a historic pioneer, characteristically choosing to somewhat understate its importance, combining his pride in his faith and heritage with an emphasis of valuing the lack of public attention to his fixed characteristics.

“One of the most remarkable things about Britain is just how unremarkable it is that two generations after my grandparents came here with little, I could become prime minister and that I could watch my two young daughters light Diwali candles on the steps of Downing Street,” said Sunak.

In his own first words as prime minister, Sir Keir placed somewhat more emphasis on Sunak’s role as a historic pioneer than Sunak has tended to do himself. Sir Keir, the social democrat, suggested that Sunak faced extra barriers and hurdles due to his ethnicity: “the extra effort that that will have required should not be underestimated by anyone”.

Sunak, as a liberal conservative, has tended to prefer to cast himself as having been the recipient of educational privilege and professional fortune for which he is grateful, giving his motivation for coming into politics and public life as the desire to give back. Yet, this 2024 election campaign – including the overt racism against Sunak from campaigners for the Reform party – did illustrate how even a fair chance to reach the very top does not in itself guarantee an equal experience of public life.

Sunak’s final message “we must hold true to that idea of who we are - that vision of kindness, decency and tolerance that has always been the British way”.

Those are noble sentiments. Sir Keir, as Sunak’s successor as prime minister, wishes to make a central theme of his pitch to bring people together. Sunak’s critics may ask how far he has always pursued those themes himself.

By instinct, Sunak has always been much more a bridger, than a culture warrior. By circumstance, the challenges of managing the Conservative party coalition have seen him come under pressure from the right.

Just as ethnic diversity became a new norm across the political parties, debates about race could often become more polarising than ever.

Left to his own devices, Sunak would have focused his premiership on the quest for economic growth – and his belief in education, and more maths for all, as the key to future productivity. Yet if his premiership was defined by one issue, it was the Rwanda scheme – and the pledges to stop the boats that he was unable to keep. The Rwanda plan was on the ballot paper in this general election - and did not bring the electoral dividends that the Conservatives hoped it might. Labour now has a clear mandate to scrap the plan – and to show that it can find a more constructive alternative.

Sunak’s short political career – he leaves as prime minister just nine years after entering parliament – has seen both the highs and lows of public life. Few politicians have ever been as unpopular as the relatively unknown chancellor of the exchequer who gave security and peace of mind to so many people during the pandemic with the furlough scheme. Yet this election campaign showed how unforgiving the public can be towards any mistake once minds have been made up that it is time for change.

Was Sunak handed an impossible job when he became the third prime minister in a matter of months in the autumn of 2022? Or could he have made better choices in office. Strong points can be made on both sides of this argument. On becoming prime minister, Sunak personally had a much better public reputation than the Conservative Party. But after two years in office, their reputations had converged — downwards. Having not been elected either by the public or the party, perhaps he lacked the standing to challenge internal political pressure and infighting.

This campaign has exposed several of Sunak’s weaknesses in political campaigning - yet history may well be kinder to him. Sunak was not able to be the political miracle worker that his party needed to get another opportunity to govern after 14 long years. Yet the grace and dignity of this transition of power speaks to a public mood keen to move.

Sunak will surely not be the last British Asian party leader or prime minister. While he may like to value that, it should not be seen as such a big deal - that he was the first will make it easier for those who follow him.

(The author is the director of British Future)

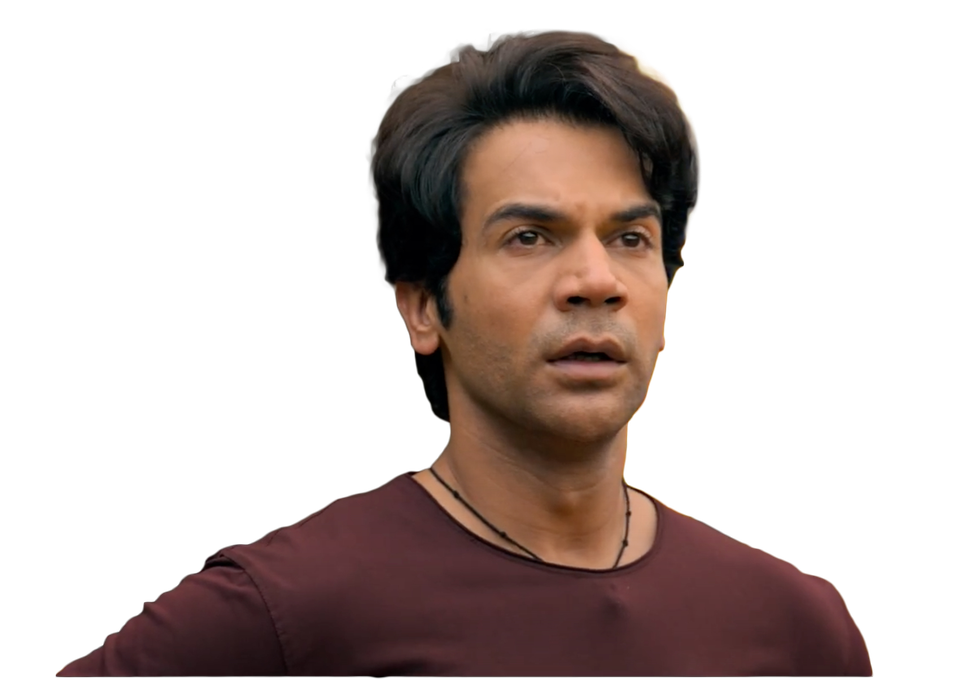

Bhool Chuk Maaf

Bhool Chuk Maaf If You Know You Know

If You Know You Know Asif Khan

Asif Khan Sanam figure out why. Teri Kasam

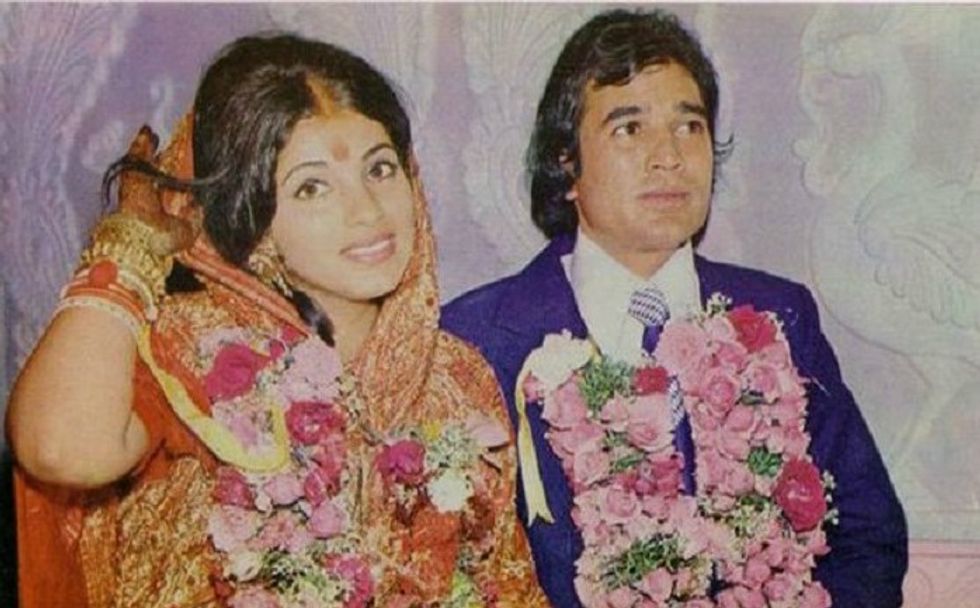

Sanam figure out why. Teri Kasam Dimple Kapadia and Rajesh Khanna on their wedding day

Dimple Kapadia and Rajesh Khanna on their wedding day Atif Aslam

Atif Aslam

Anoushka Shankar

Anoushka Shankar Nilesha Chauvet

Nilesha Chauvet

Pieter Elbers

Pieter Elbers