No issue has caused Rishi Sunak more trouble as prime minister than immigration. He identifies himself as a prime minister with a plan, determined to deliver. That has been a challenging battle on the economy and public services, but has been most difficult of all on immigration.

The government has increased the public salience of immigration – the extent to which it matters to voters – over the past two years. But that rise in salience has been combined with declining public trust in the government’s ability to manage it well.

Satisfaction with the government’s handling of immigration has fallen to just nine per cent in the latest Ipsos-British Future Immigration Attitudes Tracker, which has surveyed opinion on immigration since 2015. That is an all-time low.

The significant post-Brexit softening in public attitudes towards immigration has stalled over the last two years. A slim majority of the public now favours reducing overall numbers: 52 per cent say they would like to see overall numbers fall, a rise from 48 per cent last year. That is the highest support for reductions since 2020, though it had two-thirds support before 2016. A third (35 per cent) would like to see large reductions in overall immigration.

Yet the dilemmas of control remain – not just for government ministers, but for the public too. There is little public appetite to cut those visas that have contributed most to the rising numbers. Health and social care made up half of visas for work in 2023. Majorities of the public say they would like to increase the numbers of doctors and nurses, with just one in six prepared to reduce numbers.

Only 18 per cent of people would reduce the number of people coming to work in care homes, but seven out of ten would not; 42 per cent would prefer the numbers of social care visas to rise. Over a third of respondents would reduce numbers of international students, though there is public support for the two-year post-study work visa after graduation.

Sunak is under much more pressure than Labour leader Sir Keir Starmer over immigration numbers. Seven out of ten Conservatives want reductions in the levels of immigration – and 52 per cent would like to see large reductions in the numbers – while most Labour voters say that they are content with the current levels. Among Labour voters, a fifth want large reductions and another fifth favour further increases, demonstrating the breadth of the electoral coalition that Starmer must balance.

As chancellor under Boris Johnson, Sunak was part of the government that oversaw record increases in immigration. As prime minister, he is now committed to delivering the largest ever reductions. The government estimates that its December 2023 policy package would prevent around 300,000 people who got a UK visa last year getting one now – largely by targeting visas for dependents.

Sunak is under pressure from his backbenchers to do more. Yet, any further policy changes will not show up in the pre-election numbers; they would instead contribute to the statistics released by the next government. The legacy of missed targets means that future promises may be heavily discounted now.

The government hit further delays on its Rwanda plan last week, responding to a second set of Lords amendments by delaying its ‘emergency legislation’ beyond Easter. Our survey finds most people doubt there will be any pre-election flights to Rwanda, so Sunak may still hope to exceed those expectations this summer. There is also public scepticism about whether the purported deterrent effect would materialise.

The scheme divides the public in principle and practice. Some 47 per cent say they support the scheme, but only 32 per cent back removing people to Rwanda without first hearing their asylum claim in Britain first, as the scheme proposes. Over half think the claims should be heard in Britain – with 26 per cent open to considering removals to Africa for those whose claims fail and 25 per cent opposed entirely.

Immigration is often said to be a polarising issue. Sunak’s political headache is to find himself equally unpopular at both poles of the debate. There is 74 per cent mistrust of Sunak among the quarter of the public with the most liberal views – and 77 per cent mistrust among those with the toughest views, with whom he has specifically been trying to reconnect.

There is a broad ‘balancer’ middle of public opinion on immigration too, which is neither ‘pro’ nor ‘anti’. Among this group, which sees both pressures and gains from immigration, there is 68 per cent disapproval of the prime minister – because they doubt his government’s competence to manage either effectively.

All parties struggle for trust on immigration – but the parties and politicians with the toughest messages do not fare better than their rivals. Reform UK, the Greens and the Liberal Democrats are all trusted by around a quarter of the public on immigration – from different parts of the electorate.

Labour, across Britain, and the Scottish National Party in Scotland, have the least negative ratings. Securing public trust on immigration is not just about tough talk, but about striking the balances between control, contribution and compassion.

(The author is the director of British Future)

Reshammiya in Badass Ravi Kumar

Reshammiya in Badass Ravi Kumar

Private schools have been impacted by the 20 per cent VAT imposed on them

Private schools have been impacted by the 20 per cent VAT imposed on them

Manpreet Singh

Manpreet Singh Anuja

Anuja Arpita Singh

Arpita Singh Yeh Jawaani Hai Deewani

Yeh Jawaani Hai Deewani Baby John

Baby John Punjab 95

Punjab 95 Karan Veer Mehra

Karan Veer Mehra Roshan

Roshan Emergency

Emergency

The actor with Kareena Kapoor, Sharmila Tagore and Saba Ali Khan

The actor with Kareena Kapoor, Sharmila Tagore and Saba Ali Khan Sharmila Tagore, Saba Ali Khan, Lord Jeffrey Archer, Soha Ali Khan, Saif Ali Khan and Kareena Kapoor at a 2013 event

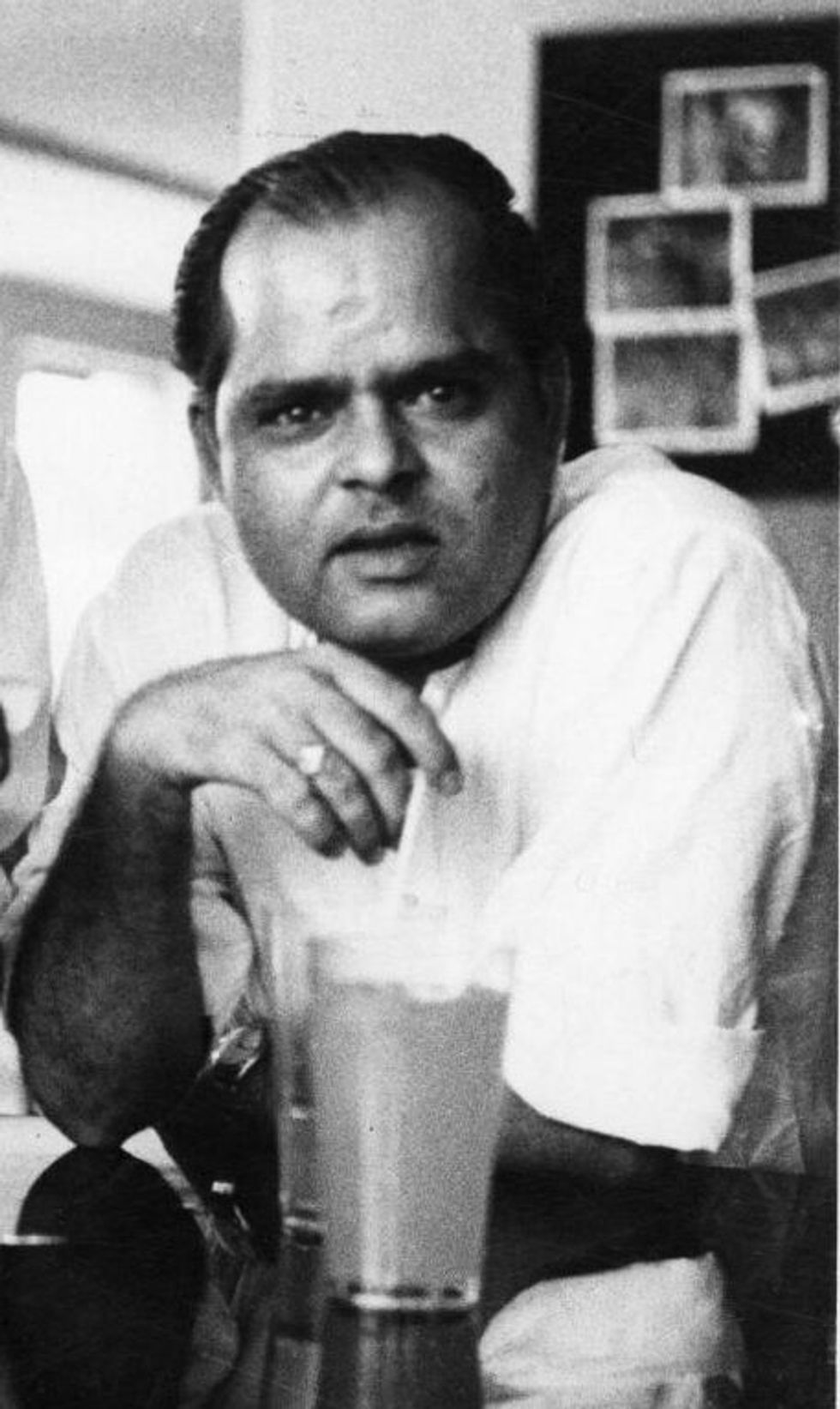

Sharmila Tagore, Saba Ali Khan, Lord Jeffrey Archer, Soha Ali Khan, Saif Ali Khan and Kareena Kapoor at a 2013 event Saif's father, Nawab of Pataudi, Mansur Ali Khan

Saif's father, Nawab of Pataudi, Mansur Ali Khan