The general election arguments may be stilled, at least briefly, this Thursday (6) as the nation pauses to commemorate 80 years since the D-Day landings. This anniversary week has been marked by poignant gatherings of those who were once young soldiers of 19 and 20 when they landed on the Normandy beaches. They now look back, aged 99 or 100, as they are honoured by King and country for what they did to help to secure the democratic freedoms that we may often take for granted today.

Those landings in France, a return to the western front abandoned in the Dunkirk evacuation of 1940, were a crucial staging post in the defeat of Hitler’s Nazi regime a year later.

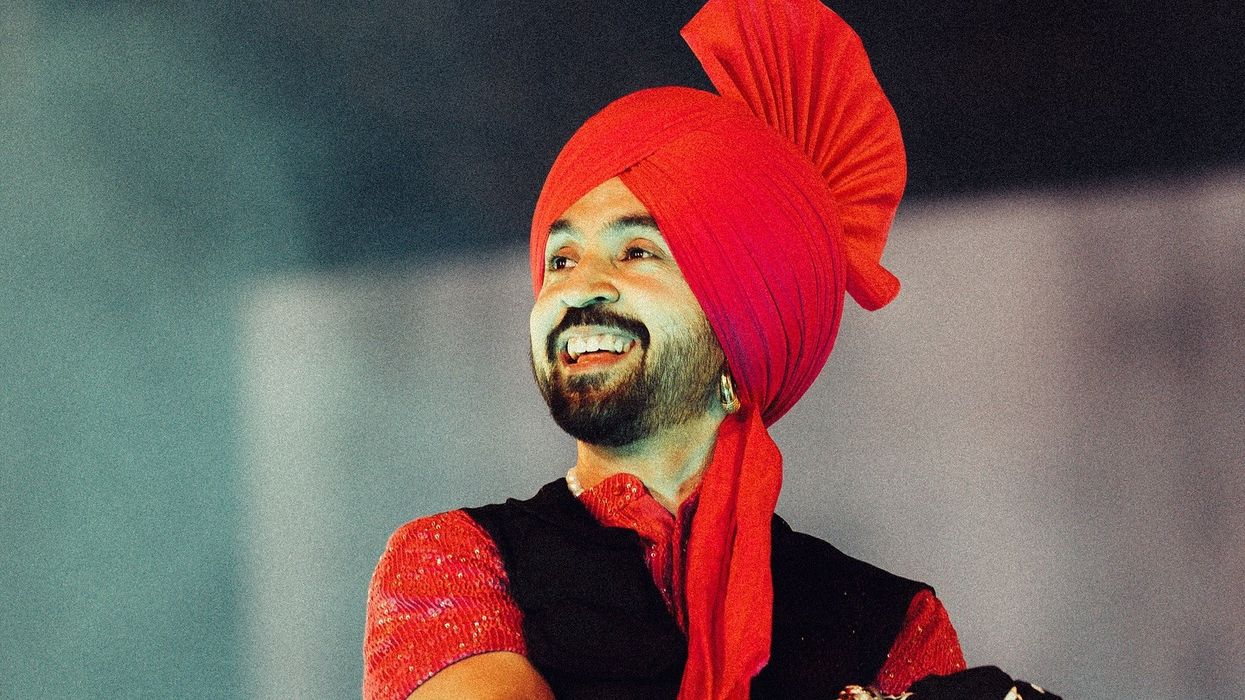

Yet, winning a world war took a global effort. D-Day was part of a year in which service personnel from across Britain and the Commonwealth fought important battles from Monte Cassino in Italy to Burma and northern India. So, the 1944 Victoria Cross roll of honour includes Sikh, Muslim and Hindu soldiers from India, as well as Nepalis from the Gurkha regiments.

In their ethnic and faith mix, the armies that fought and won the world wars resemble more closely today’s Britain of 2024, rather more than that of 1944 or 1914. So, the service of Commonwealth forces from Asia, Africa, the Caribbean and beyond should be recognised for its foundational contribution to our shared society today.

The Indian army’s contribution of 2.5 million soldiers to the Second World War was the largest volunteer army in history. There was a significant spike in public awareness during the 2014-2018 first world war centenary, when it became something that most people had heard about.

Six out of ten people now know that Indian soldiers were part of the world wars, according to new Focaldata research for British Future. Almost half of the public recognise that Hindu and Sikh soldiers fought for Britain in the world wars – yet only 38 per cent know that Muslim soldiers served alongside them. That reflects a doubling of awareness on a decade ago, but it does again mean that most people are unaware of the service of huge numbers, mostly from modern-day Pakistan, who fought for Britain. There is similarly limited awareness, among just 38 per cent of the public, of the service of Jewish soldiers.

Only 35 per cent know about the service of those from Jamaica and just 30 per cent know that Kenyans also fought for Britain. The Royal Air Force (RAF) belatedly lifted its colour bar after war broke out in 1939, so a third of the passengers on the Windrush in 1948 were RAF servicemen returning to Britain. They had served alongside Polish airmen, as well as those from across the UK. Understanding that link from war to Windrush is a crucial foundation for understanding the country that we are today.

Despite patchy public knowledge about who took part, the attitudes research finds a broad consensus of the contemporary importance of knowing this history. Some 85 per cent of the public feel it is important that people know about the role of soldiers from the empire and Commonwealth in the British war effort. A majority say we talk too little about this aspect of the history. Only a surly five per cent say they hear too much about the Commonwealth soldiers.

When the General Election campaign resumes, we may hear more heated partisan arguments about identity. Nigel Farage has shaken up the election campaign by deciding to stand as a candidate and becoming Reform Party leader again. Yet Farage’s first contribution to the General Election campaign was a sharp clash with Sky broadcaster Trevor Phillips, who objected strongly to the sweeping way in which Farage contrasted West Indian and Muslim integration in Britain.

Farage had cited both wartime service and (bizarrely) “love of cricket” as examples of a shared history and culture that he felt Muslims would be much less likely to share. Arguments challenging extremism or critiquing integration can cross the line into casual prejudices if they articulate and reinforce monolithic stereotypes of minority groups as an existential threat. “I just wonder, are we heading for some form of religious war?” Farage had asked on GB News last autumn in the run-up to Remembrance Sunday.

There is evidence that hearing about both historic and contemporary Muslim contributions to the armed forces can help to break down stereotypes, particularly among those with least real-world contact, helping to undermine prejudice and fear. As I argue in my book, How to be a Patriot, shared moments like Remembrance can help bring people together.

Prominent voices from the military, faith and civil society this week signed a joint letter in The Times urging that Commonwealth forces are not overlooked. Next year’s 80th anniversary of VE Day in 2025 should be seized as an opportunity to increase public understanding of every contribution to our shared history. Remembering that service and sacrifice together can help to strengthen our common ground today in often polarised times.

(The author is the director of British Future)