THE Netflix series Bridgerton with two British Asian actresses in lead roles – Simone Ashley and Charithra Chandran play sisters Kate and Edwina Sharma, newly arrived from India – have upended the claims that English period dramas such as Downton Abbey cannot have multicultural casting because this would not be authentic.

Ashley (who Anglicised her name from Simone Ashwini Pillai), 26, and Chandran, 22, were born in the UK to Tamilian parents from Sri Lanka and India, respectively. When Ashley’s casting was announced, she quipped: “Hey, a message to all dark-skinned desi girls, put down that fairness cream, you don’t need it.”

Chandran agreed: “It’s really exciting to be able to play that (Indian) perspective. They have different customs, a different background, and they’re being transplanted into this new environment. That brings a whole new element to it all.”

Back in 2014, Gareth Neame, executive producer of Downton Abbey, told the New York Times that his show could not have black and Asian people: “It’s not a multicultural time. We can’t suddenly start populating the show with people from all sorts of ethnicities. It wouldn’t be correct.”

The New York Times hit back: “Bridgerton provides a blueprint for British period shows in which black characters can thrive within the melodramatic story lines, extravagant costumes and bucolic beauty that make such series so appealing, without having to be servants or enslaved. This could, in turn, create openings for gifted performers who have avoided them in the past.”

Historians say that black and brown people did live in Regency England where Bridgerton is set. It is said that Queen Charlotte (1744-1818), the wife of King George III, was of African origin and “Britain’s first black queen”. References to Charlotte surfaced when Meghan Markle married Prince Harry.

Bridgerton’s creator, Chris Van Dusen, told the New York Times, that he chose “to base the show in an alternative history in which Queen Charlotte’s mixed-race heritage was not only well-established, but was transformative for black people and other people of colour in England”.

The first series of Bridgerton, which was streamed to 82 million households across the globe, has proved to be Netflix’s most popular drama. However, it has taken Americans to usher in revolution into period English drama, hitherto the exclusive preserve of white performers.

Set between 1813 and 1827, the Bridgerton series is a collection of eight novels by Julia Quinn, a best-selling US historical romance author whose books have been translated into 41 languages.

Each features one of the eight children of the late Viscount Bridgerton – Anthony, Benedict, Colin, Daphne, Eloise, Francesca, Gregory, and Hyacinth. The first four novels include a mysterious gossip columnist called “Lady Whistledown”, who was the Nigel Dempster of her day.

The first series was based on The Duke and I; the second, which began last Friday (25), on The Viscount Who Loved Me.

The other novels are – An Offer From A Gentleman; Romancing Mr Bridgerton; To Sir Phillip, With Love; When He Was Wicked; It’s In His Kiss; and On The Way To The Wedding.

The real power behind Bridgerton is its executive producer, Shonda Lynn Rhimes, an American television producer, screenwriter and author, who is herself a black woman.

“Making the Sharmas of south Asian descent was actually a very simple choice,” she said. “I wanted to feel like the world we were living in was as three-dimensional as possible, and I wanted to feel like the representation was as three-dimensional as possible, too.

“Finding south Asian women with darker skin and making sure they were represented on screen authentically and truthfully feels like something we haven’t seen nearly enough of. I felt like it was time for us to make sure that we were seeing as much as possible.”

Her comment is a rebuke to Bollywood where leading ladies are invariably pale-complexioned.

“And it wasn’t just me,” Rhimes added. “The entire creative team was excited and on board with this idea from the very beginning. And the idea that they are from another culture, we weave that into the story in a wonderful way to enhance the idea that the very English values of our characters are not necessarily the only values worth having.

“That’s reflected in Kate’s reaction to English tea – but really, it is a very important way of making sure that we are including the world in this.

“Netflix has a global audience. That audience is the world, literally. I wanted to make sure that if you are watching Bridgerton from another country, you’re not thinking to yourself, ‘Well, this has nothing to do with me.’

“Well, absolutely it has something to do with you. The humanity in every character should feel universal.”

On the significance of the show’s multicultural casting, she said: “I’m not sure that it’s just important to the show’s identity as it is important to television and shows in general. The idea that we don’t create worlds that look like the world we live in, and we create false societies where everybody looks a certain kind of way or is a certain kind of colour or whatever, feels disingenuous to me.

“It also feels like erasure. We’re just not interested in erasing anybody from the story, ever. That is how we do it, that’s just how we tell stories. While it’s important for Bridgerton, it’s important for every story being told. When you’re watching television, you should get to see people who look like you.”

That was reflected behind the camera as well, she added – something that Krishnendu Majumdar has also being trying to do as the first non-white chairman of Bafta.

Rhimes said: “We make sure the crew and the people behind the scenes are as multicultural as the people you see in front of the camera. We make sure they are different in age, we make sure they have different abilities. We like to make sure our casts and our crews and our writers represent the real world.

“I think it makes for better storytelling, it makes for more authentic storytelling, and it makes for more complex storytelling. You want directors who reflect the world. You want people who have a view of the world that doesn’t come from simply one point of view.

“There’s nothing wrong with a white male point of view, but there are certainly many things right about the point of view of women of colour, directors of colour, artists of colour, writers of colour. It feels important to include that in our world.”

'The Guilt Pill' her latest booksaumyadave.com

'The Guilt Pill' her latest booksaumyadave.com

Milli Bhatia

Milli Bhatia

Prithviraj Kapoor and Ramsarni Mehra Reddit/ BollyBlindsNGossip

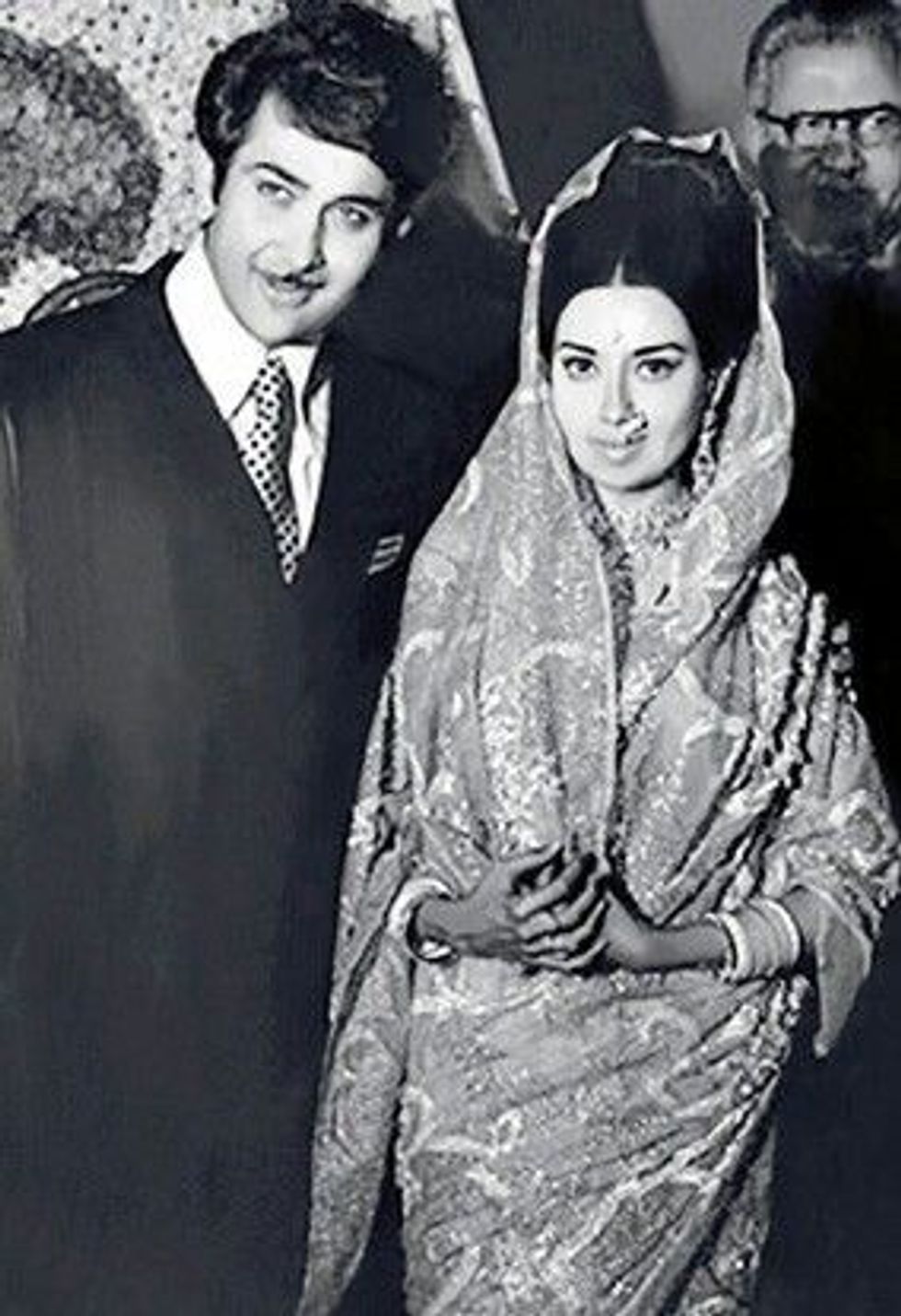

Prithviraj Kapoor and Ramsarni Mehra Reddit/ BollyBlindsNGossip Raj Kapoor and Krishna MalhotraABP

Raj Kapoor and Krishna MalhotraABP Geeta Bali and Shammi Kapoorapnaorg.com

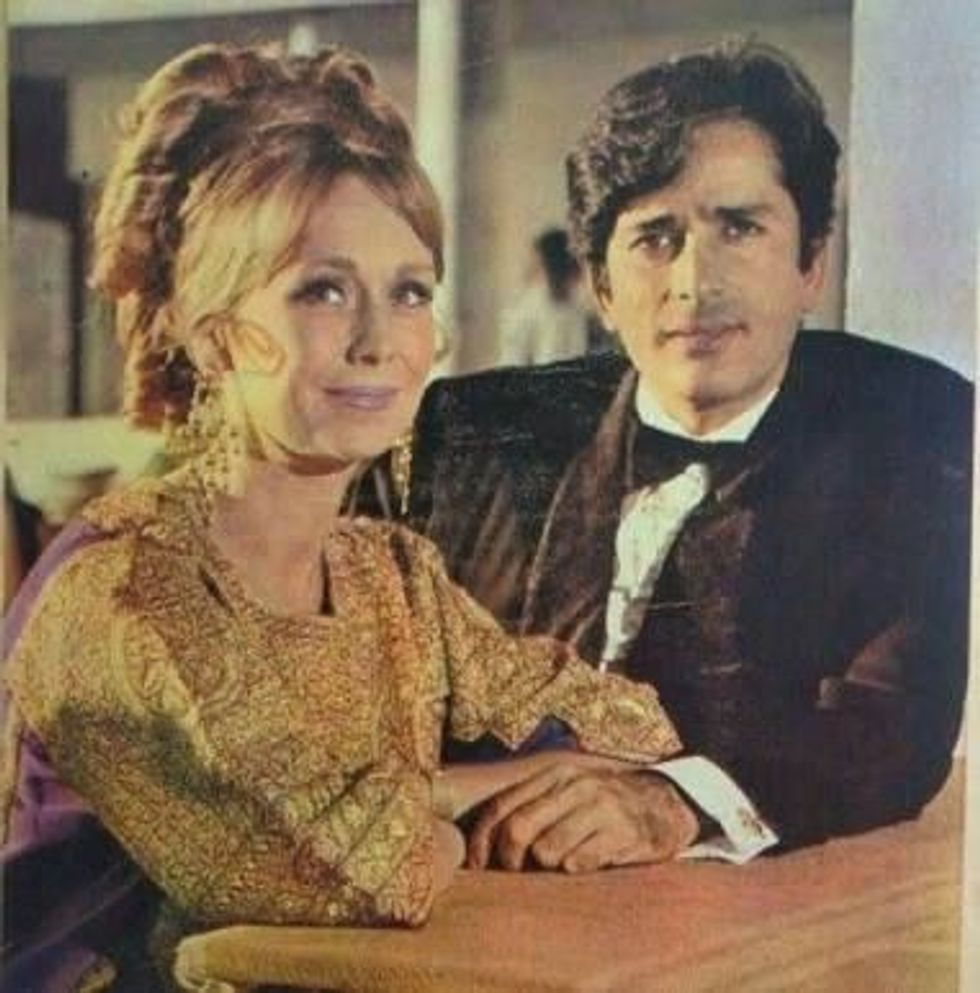

Geeta Bali and Shammi Kapoorapnaorg.com Jennifer Kendal and Shashi KapoorBollywoodShaadis

Jennifer Kendal and Shashi KapoorBollywoodShaadis Randhir Kapoor and Babita BollywoodShaadis

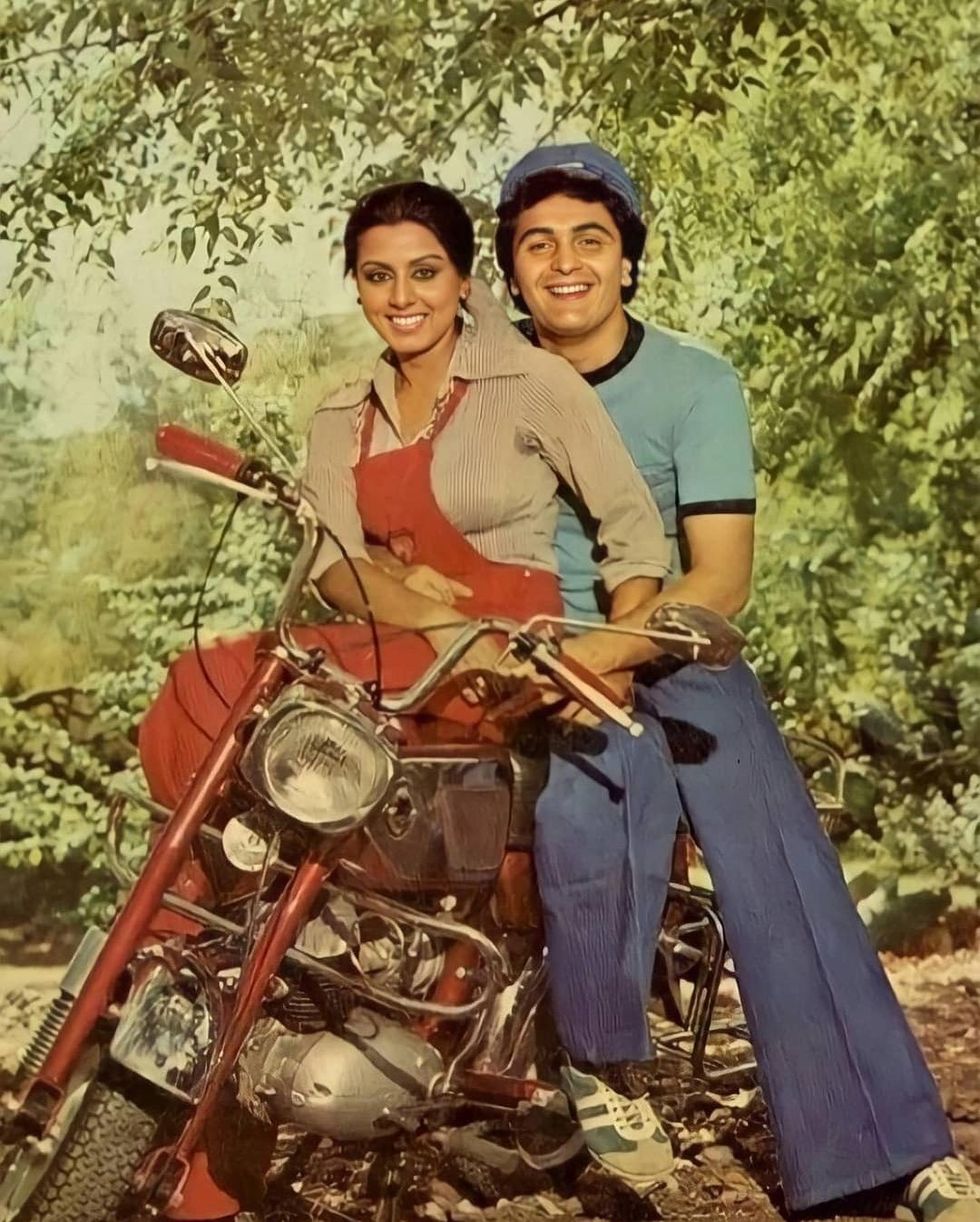

Randhir Kapoor and Babita BollywoodShaadis Neetu Singh and Rishi KapoorNews18

Neetu Singh and Rishi KapoorNews18 Rajiv Kapoor and Aarti Sabharwal Times Now Navbharat

Rajiv Kapoor and Aarti Sabharwal Times Now Navbharat Alia Bhatt and Ranbir KapooInstagram/ aliaabhatt

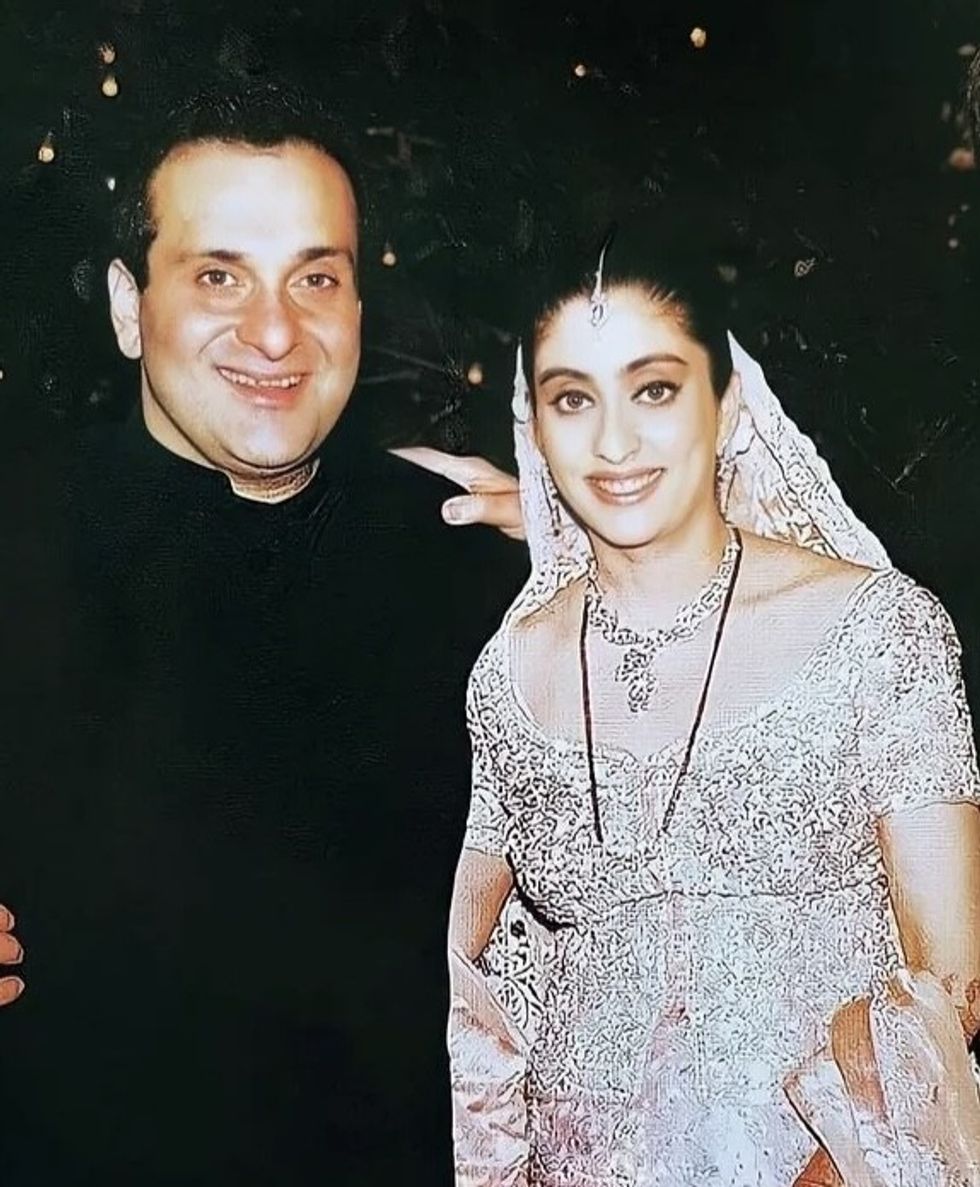

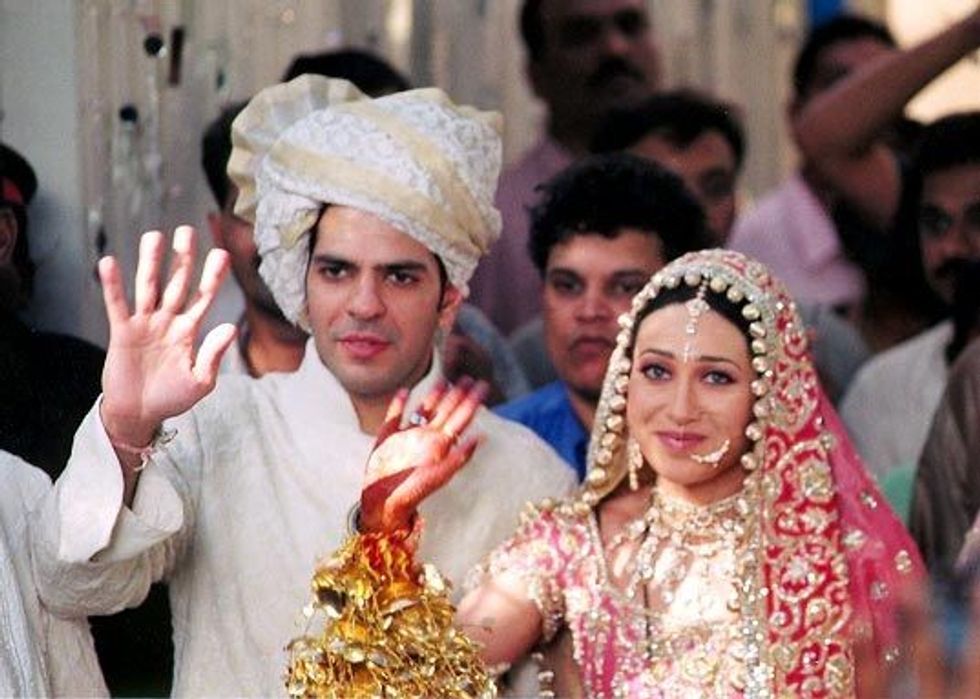

Alia Bhatt and Ranbir KapooInstagram/ aliaabhatt Sunjay Kapur and Karisma KapoorMoney Control

Sunjay Kapur and Karisma KapoorMoney Control

With actor Kanwar Dhillon in 'Ram Bhavan'Instagram/ rahultewary

With actor Kanwar Dhillon in 'Ram Bhavan'Instagram/ rahultewary Udne Ki AashaScreen Grab 'Udne Ki Aasha'

Udne Ki AashaScreen Grab 'Udne Ki Aasha'