AUSTRALIA returned Novak Djokovic to detention on Saturday (15), saying the tennis star's opposition to vaccination could cause "civil unrest" and triggering a high-profile court showdown.

Having once failed to remove the unvaccinated 34-year-old from the country, Australia's conservative government is trying again.

And Djokovic is fighting back for the second time, with a new court appeal scheduled for Sunday (16).

The case will be heard from 9:30 am (2230GMT) by the full Federal Court of three justices, a format that leaves little room to appeal any decision.

For now, the Serbian ace is back at a notorious Melbourne immigration detention facility after a few short-lived days of freedom following his first successful court appeal.

A motorcade was spotted moving from his lawyers' offices - where he had been kept under guard for most of Saturday - to the former Park Hotel facility.

For millions around the world, the Serbian star is best known as a gangly all-conquering tennis champion with a ferocious backhand and his anti-vaccine stance.

In court filings, Australia has cast him as a figurehead for anti-vaxxers and a catalyst for potential "civil unrest" who must be removed in the public interest.

Djokovic's presence in Australia "may foster anti-vaccination sentiment", immigration minister Alex Hawke argued, justifying his use of broad executive powers to revoke the ace's visa.

Not only could Djokovic encourage people to flout health rules, Hawke said, but his presence could lead to "civil unrest".

So with just two days before the Australian Open begins, the defending champion is again focused on law courts rather than centre court.

Second serve

After months of speculation about whether Djokovic would get vaccinated to play in Australia, he used a medical exemption to enter the country a week ago, hoping to challenge for a record 21st Grand Slam title at the Open.

Many Australians - who have suffered prolonged lockdowns and border restrictions - believe Djokovic gamed the system to dodge vaccine entry requirements.

Amid public outcry, prime minister Scott Morrison's government revoked Djokovic's visa on arrival.

But the government was humiliated when a judge reinstated Djokovic's visa and allowed him to remain in the country.

This time, the government has invoked exceptional - and difficult to challenge - executive powers to declare him a threat to public health and safety.

Experts say the case has taken on significance beyond the fate of one man who happens to be good at tennis.

"The case is likely to define how tourists, foreign visitors and even Australian citizens view the nation's immigration policies and 'equality before the law' for years to come," said Sanzhuan Guo, a law lecturer at Flinders University.

Djokovic's lawyers argue the government "cited no evidence" to support their claims.

The minister admitted that Djokovic is at "negligible" risk of infecting Australians, but argued his past "disregard" for Covid-19 regulations may pose a risk to public health and encourage people to ignore pandemic rules.

The tennis ace contracted Covid-19 in mid-December and, according to his own account, failed to isolate despite knowing he was positive.

Public records show he attended a stamp unveiling, youth tennis event and granted a media interview around the time he got tested and his latest infection was confirmed.

Djokovic is the Australian Open's top seed and a nine-time winner of the tournament. He had been practising just hours before Hawke's decision was announced.

The visa cancellation effectively means Djokovic would be barred from obtaining a new Australian visa for three years, except under exceptional circumstances, ruling him out of one of the four Grand Slam tournaments during that time.

He is currently tied with Roger Federer and Rafael Nadal with 20 Grand Slam titles each.

Serbian president Aleksandar Vucic on Friday (14) accused Australia of "mistreating" the country's biggest star, and a national hero.

"If you wanted to ban Novak Djokovic from winning the 10th trophy in Melbourne why didn't you return him immediately, why didn't you tell him 'it is impossible to obtain a visa'?" Vucic said on Instagram.

"Novak, we stand by you!"

Spanish great Nadal took a swipe at his rival on Saturday as players complained the scandal was overshadowing the opening Grand Slam of the year.

"The Australian Open is much more important than any player," Nadal told reporters at Melbourne Park.

"Australian Open will be a great Australian Open with or without him."

Defending Australian Open champion Naomi Osaka called the Djokovic saga "unfortunate" and "sad" and said it could be the defining moment of his career.

"I think it's an unfortunate situation. He's such a great player and it's kind of sad that some people might remember (him) in this way," she said.

(AFP)

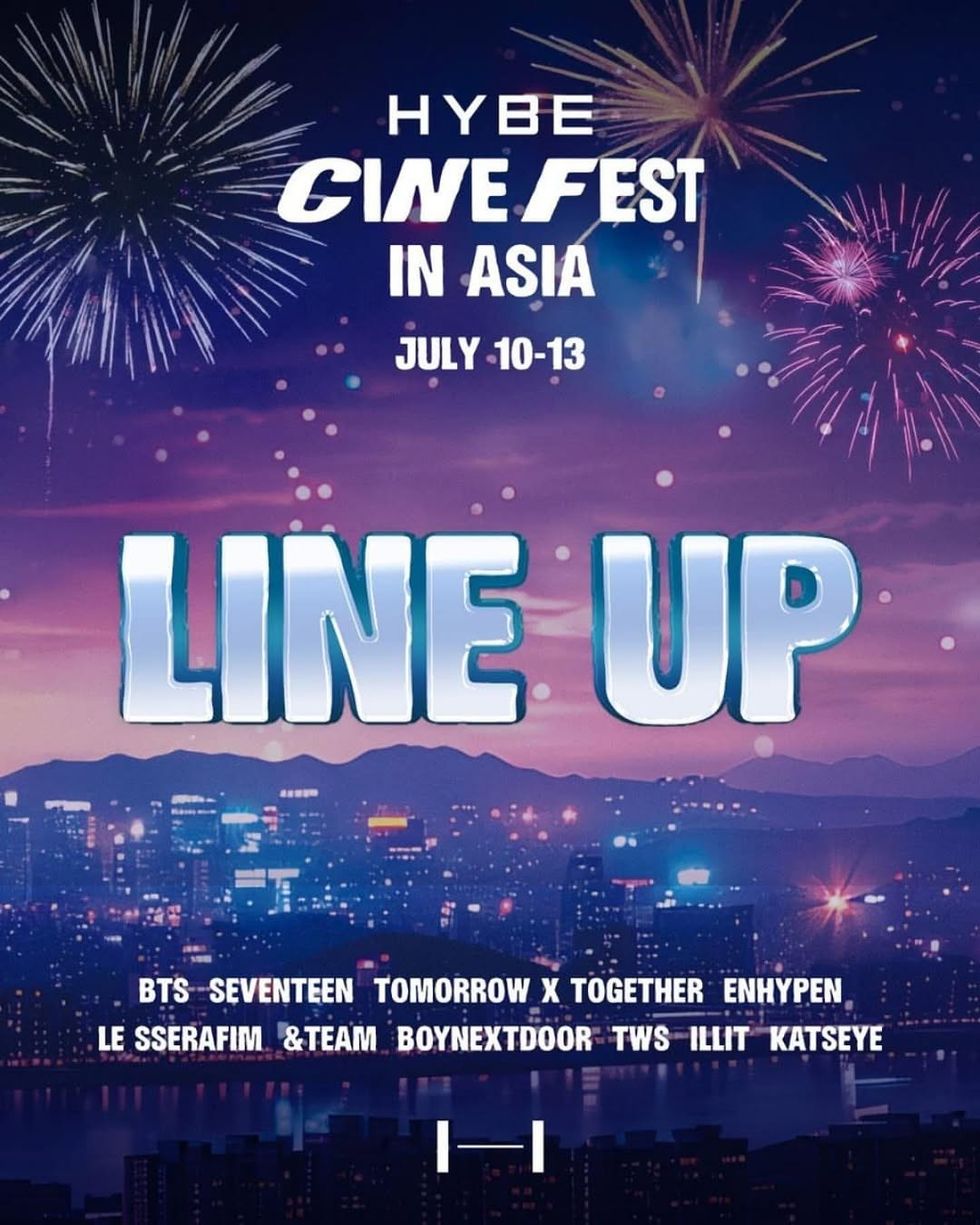

Everything you need to know about HYBE Cine Fest 2025 and line-up Instagram/

Everything you need to know about HYBE Cine Fest 2025 and line-up Instagram/ HYBE Cine Fest 2025 details Instagram/

HYBE Cine Fest 2025 details Instagram/