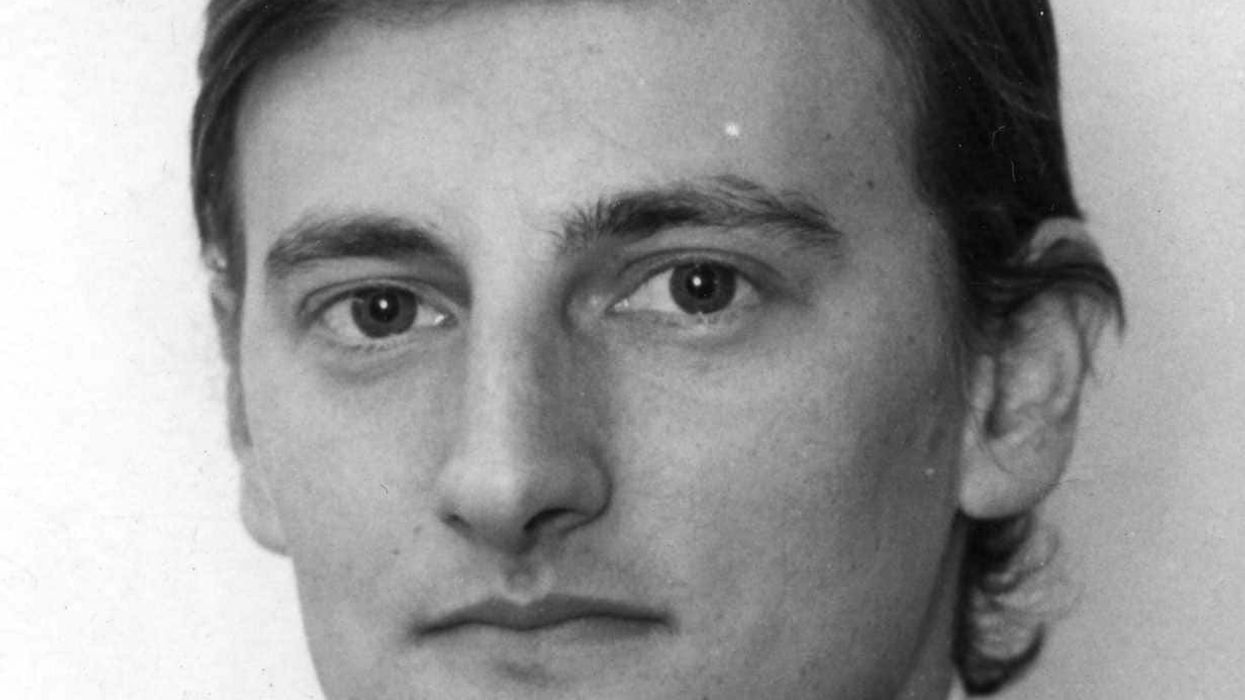

Tribute to British journalist and honorary Bangladeshi citizen Simon

YOUNGER Asians born and brought up in Britain may not have heard of the British journalist Simon Dring, who died on July 16, at the age of 76.

But for those who want to understand the circumstances leading to the secession of East Pakistan and the bloody birth of Bangladesh, his report did provide the first draft of history.

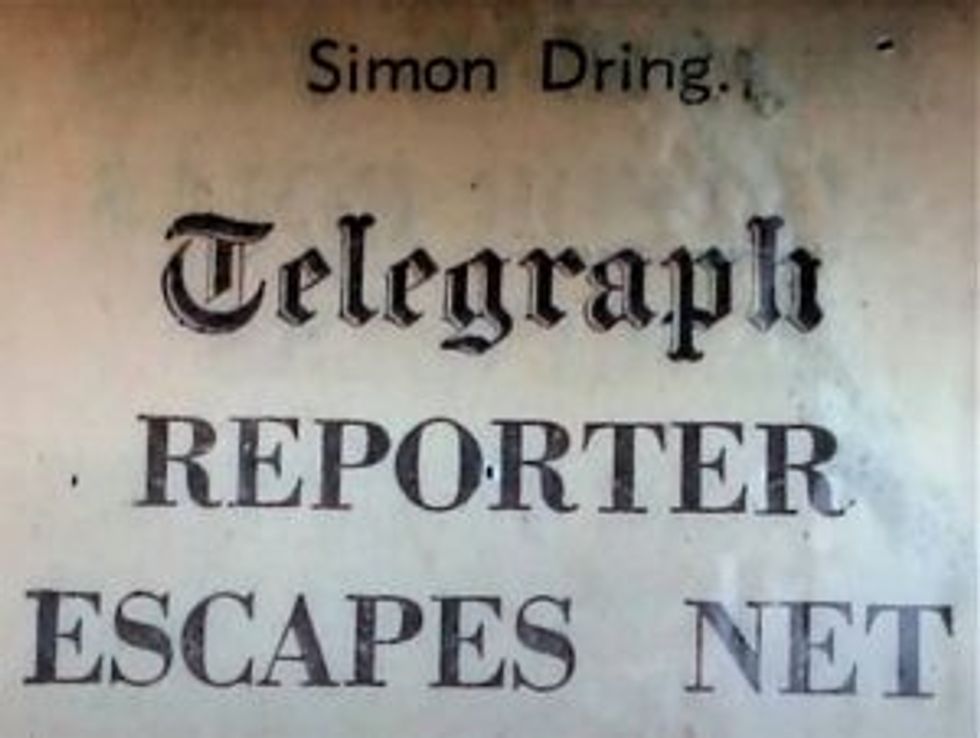

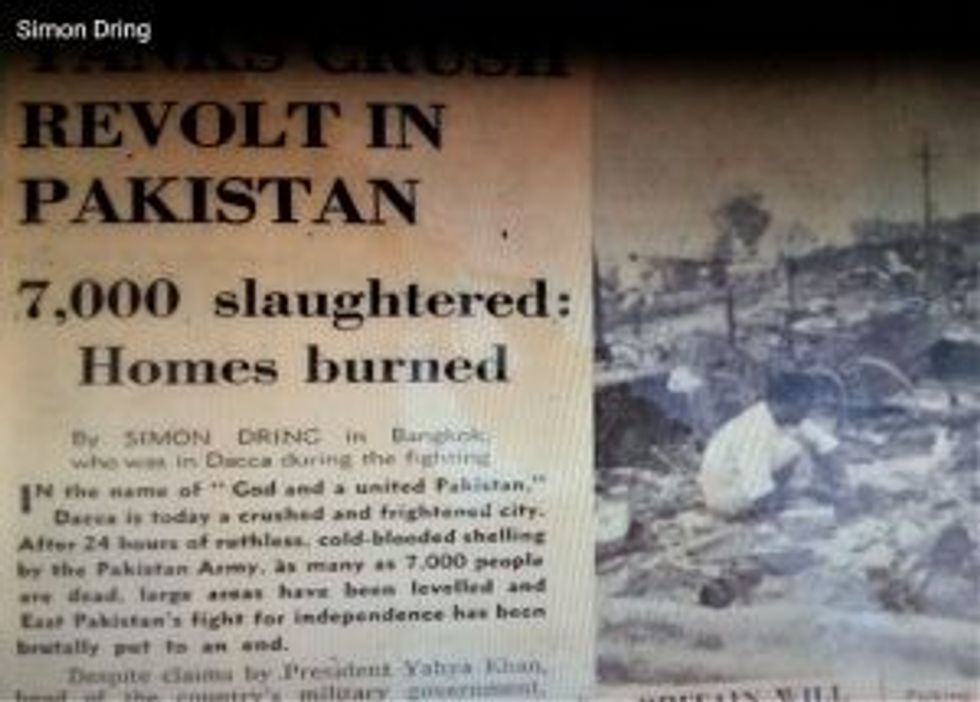

In March 1971, Dring, then a 26-year-old reporter with the Daily Telegraph in London, alerted the world to the Pakistani army’s massacre in East Pakistan with a frontpage scoop, “Tanks Crush Revolt in Pakistan. 7,000 slaughtered.”

The paper noted that Dring had broken the story at great personal risk to himself: “Telegraph reporter escapes net.”

He was later told that had he been caught, he would almost certainly have been killed by the Punjabi-

dominated West Pakistan army in order to stop the story of their genocide getting out.

Dring’s report inspired first generation East Pakistanis in the UK into making London the centre of a campaign to support the creation of an independent Bangladesh.

Last Friday (23), Dring made the Telegraph again, this time on its obituary pages, having passed away during what was meant to be routine surgery for hernia in Romania.

He is survived by his partner, Australian human rights lawyer Fiona McPherson, and their twin daughters, as well as a daughter from an earlier marriage.

Dring, who began as a 19-year-old staff correspondent with Reuters in Vietnam, represented Fleet Street’s spirit of derring do. He covered 22 wars and revolutions around the world, but will be remembered for being present at the birth of Bangladesh, which honoured him by making him an honorary citizen.

Some 40 years later, Dring stood on the roof of the Dhaka Intercontinental, where he had hidden in 1971, and recounted the horrors he had witnessed. As tension in East Pakistan mounted, his paper moved him from Cambodia to Dhaka on March 6. On March 7, he heard Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, leader of the Awami League, give a call for independence at the race course – “I don’t speak Bengali... I promise you, the hairs almost stood up on the back of my neck because I didn’t understand it, but I understood it.”

If ever a movie is made of Dring’s adventures, along the lines of Hollywood’s The Killing Fields, someone suitable will have to be cast as the baddie. Dring said: “And sure enough, on the evening of the 26th, when there was still shooting going on…the man who was liaising with the foreign press, a Pakistani intelligence officer, Major Siddiqui, came to the hotel, and spread the word out among the journalists that civil war had broken out and for our own safety, we would have to leave…. otherwise we might be killed by the ‘Bengali bu****s. We are going to take you out of the country.’

“I said, ‘Major Siddiqui, I’m Simon Dring of the Daily Telegraph.’ He said, ‘Yes, I know who you are.’

I said, ‘I hear that we have to leave.’ He said, ‘Yes, for your own safety.’ I said, ‘Well, is this an order?’ ‘Oh no, it’s not an order. Just for your own safety.’ I said, ‘So, I can stay?’

He said, ‘You can but it might be dangerous for you.’ So I said, ‘Well, what will happen if I stayed?’ He

said, ‘Well, there might be a party for you.’ Whatever that meant.”

Nearly 200 journalists were forced to leave on the Pakistan Airlines shuttle service to Karachi.

But Dring and AP [Associated Press] photographer Michel Laurent hid in the hotel, went round Dhaka, and recorded the killings that had taken place.

At Dhaka University, said Dring, “I counted about 30 bodies….In the dormitories of Iqbal Hall, there was a lot of blood. I saw a student dead in bed. There were students lying in the lake...the army had set up mortars on top of the British Council and mortared the campus area, then they’d gone in and just shot people...in the market area, about 200 yards of houses had been burned. There were people dead in front of the shops. ….in the Hindu area, there was a very deliberate attempt to kill people. .. Razzakars (traitors) pointing which houses were supporters of Sheikh Mujib and the occupants were taken out and killed.…I met one police officer.

He had 240 officers in his division. He found 30 of them, all dead.

“In the old part of the city...large areas had been burned, just razed to the ground. The tactic was the Pakistan army would come to the end of the street. They would send a unit down shooting into the houses, followed by another unit that poured petrol, and they set fire to the shanty houses. And those inside were burnt alive. If they ran out, they were shot dead.

“In Rajarbagh, police lines there were 1,100 police in dormitories...they’d fired incendiary devices into dormitories. Most of them were burned down ...Michel and I realised that the scale of the massacre was really extensive.

“... We estimated probably in the region of 7,000 people could well have lost their lives over that 24-hour period. And every place we went there was no indication of anybody shooting at the Pakistan army. This was clearly a deliberate attempt to kill people, to teach the people a lesson, to say to them, ‘Forget about independence. This is united Pakistan, this is Pakistan.’”

He said: “The problem we then had was how do we get this film out? How do we get my notes out without losing them? I called the British high commission but they were extremely unhelpful. They took the attitude, ‘If you’re supposed to leave, the Pakistan army told to leave, you should have left. There is not much we can do.’ They certainly weren’t going to help take our film out.”

A German couple arranged for their embassy to take out nine rolls of film, but these disappeared. On March 28, Dring escaped via Karachi to Bangkok, from where he filed his story. As the plane was about to leave Dhaka, Dring spotted Siddiqui on the runway.

During a refuelling stop in Colombo, “I called the British high commission to ask them to help us get asylum and they told us to go away. So anyway, we ended up in Karachi that night.”

In Karachi, both Dring and Laurent were strip-searched, but the hidden notes and film rolls were not detected. Nine months later, when Dring returned to an independent Bangladesh with the Mukti Bahini (Bangladeshi guerrilla fighters) in an Indian tank, the dialogue with Siddiqui got even better. After a war with India, the Pakistani army surrendered and 93,000 of its soldiers were taken prisoner.

Dring recalled: “One of the first things I wanted to do was to go and find Major Siddiqui. And I found him and it gave me great pleasure to walk up to him and say, ‘Major Siddiqui, how are you? I am really sorry that you have ended up here. Really sorry. For your own safety, obviously, you are here.’ And he sort of smiled a bit and said, ‘Yes. Things do change, don’t they?’

“I said, ‘... I’ve been waiting nine months to ask you this. What would you have done if you’d found me?’ He said, ‘We would probably have killed you.’ I said, ‘Well, at least you’re honest.’ He said, ‘Well, put it this way, we wouldn’t have killed you. You would have been killed in the crossfire because we were telling you, you have to leave for your own safety.’

“And it’s true, they could not have afforded to let us out. So they could easily have found a way to have us killed, and our bodies left on the street. And they would have got away with it. So it was very nice to at least confront him that way.”

Dring said the “crowning moment” was Sheikh Mujibur’s release from prison in West Pakistan and return – via London – to an independent Bangladesh.