MEET Richie Saint, a capable, charming but ultimately imaginary politician bidding to be prime minister of this country.

The son of a GP and a chemist was head boy at a top private school, with a first in PPE at Oxford followed up by a Stanford MBA. Saint met his wife in California too. She is the daughter of a tech billionaire, augmenting the millions he made himself in investment banking. He doesn’t bang on too much about supporting Southampton FC, but often dons green wellies to show he understands Yorkshire farming folk, not just hedge-funders.

This rising star of the David Cameron era declared for Leave in the 2016 EU referendum. But few outside Westminster had heard of him when he became chancellor just before Covid – and the most popular politician during the pandemic. His resignation from Boris Johnson’s government has divided party opinion more.

Would Conservative party members be ready for Richie? This simple thought experiment – about a white British politician whose career closely mirrors that of Rishi Sunak – illuminates one issue.

Anybody who thinks ethnicity is a decisive factor must believe that Saint would beat Liz Truss even as Sunak trails.

In this economy, Saint would struggle too. Sunak’s ethnicity has certainly not changed in the last six months, but the economy and his public reputation have.

Sunak was badly dented by a spring triple whammy – his Covid fine, the scrutiny of his US green card and his wife’s non-dom status. On policy, he faces fire from all sides: for intervening too much, with higher taxes; and too little, given soaring energy bills.

My hunch is that Sunak might have a slight political edge over this imaginary alter ego. Saint sounds like a mash-up of George Osborne, Jeremy Hunt and Jacob Rees-Mogg.

Sunak’s story of British Indian mobility across two generations perhaps mildly mitigates his own social privilege. Being privately educated became a drawback in leadership contests for a generation after Ted Heath became the first state-educated party leader in 1965.

Douglas Hurd, swept away by John Major’s Brixton backstory in 1990, complained that anti-Etonian bias felt like “some demented Marxist sect”. In the post-Blair era, Cameron and Johnson proved that going to Eton was not an insurmountable barrier.

William Hague’s Yorkshire Day video for Sunak shows why Tory members could choose Sunak as easily as Saint. His Richmond constituents talk about attending the rural Yorkshire selection meeting and expecting to vote for a local candidate or one with military credentials, before being wowed on the night by the British Indian candidate from faraway Southampton. Each of the 21 ethnic minority Conservative MPs won selection votes against white British rival contenders from local party electorates which are 95 per cent white.

That most members can vote for Asian and black candidates does not necessarily mean that there is zero racism in the party. For example, if one in 10 members did discriminate on skin colour, a non-white candidate would need 55 per cent among the other 90 per cent.

Surveys of Conservative voters show one in 10 express a strong preference for a hypothetical leader to be white, though the overlap with the six per cent who strongly prefer a male leader creates dilemmas within this toxic fringe. More important, evidence of gender or ethnic penalties diminish sharply when real candidates are named. Party member leadership polls placed Kemi Badenoch ahead of both Sunak or Truss.

Nationally, new research from More in Common reports that 81 per cent of voters say they would vote for a party led by an ethnic minority leader while eight per cent would not. Respondents were less sure if other people are as fair – 54 per cent think most voters could too, but one in three doubt that is true. This is more common on the left. More in Common found that its “progressive activist” segment were both most likely to be fine with an ethnic minority prime minister themselves (by 95 per cent to one per cent) yet least confident that other people would feel the same way – 48 per cent think most people could vote for a party led by an ethnic minority leader, but 44 per cent doubt it.

One political consequence of progressive pessimism – imputed prejudice, worrying that voters are not ‘ready’ – is to make Labour less likely to select an ethnic minority leader until its opponents first prove that it is safe to do so.

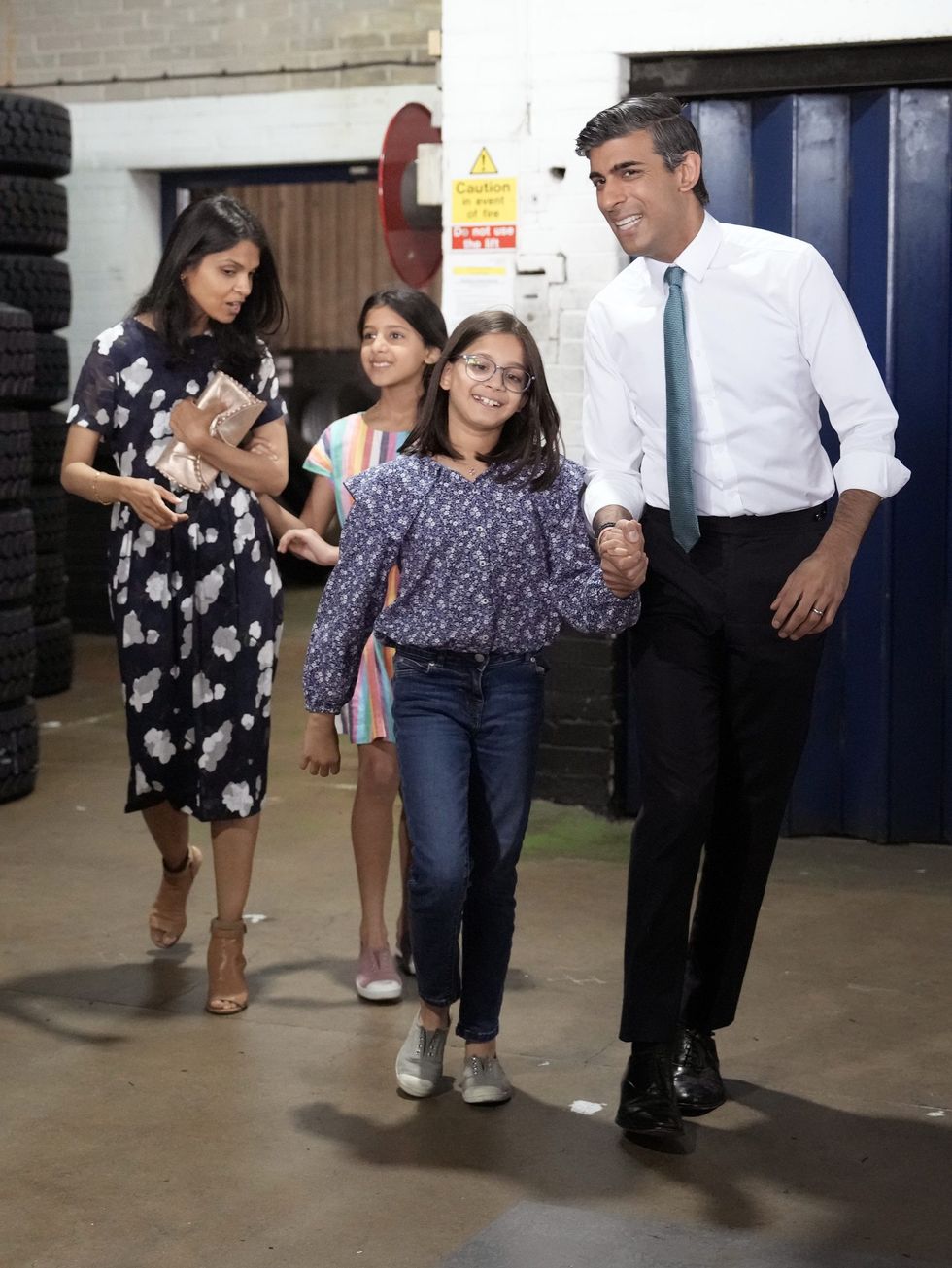

That may not be Sunak this time. Truss had her wobbliest campaign week so far, but the Sunak operation has struggled strategically. He pitched to MPs as the frontrunner willing to tell the party uncomfortable truths, before telling members what they wanted to hear after he fell behind. Sunak was himself almost a political saint as the pandemic chancellor. It is not his race or his faith, but the timing of the economic crisis that may see Sunak’s bid for the premiership sunk.

His Highness Prince Rahim Aga Khan V

His Highness Prince Rahim Aga Khan V

‘Economy, not ethnicity, may cost Sunak the race'

Tory members ‘sceptical’ about Ex-Chancellor’s cost-of-living crisis plan