BRITAIN is as racist as it was in the 1970s, and some politicians of colour are making matters worse, anti-racism campaigners have told Eastern Eye.

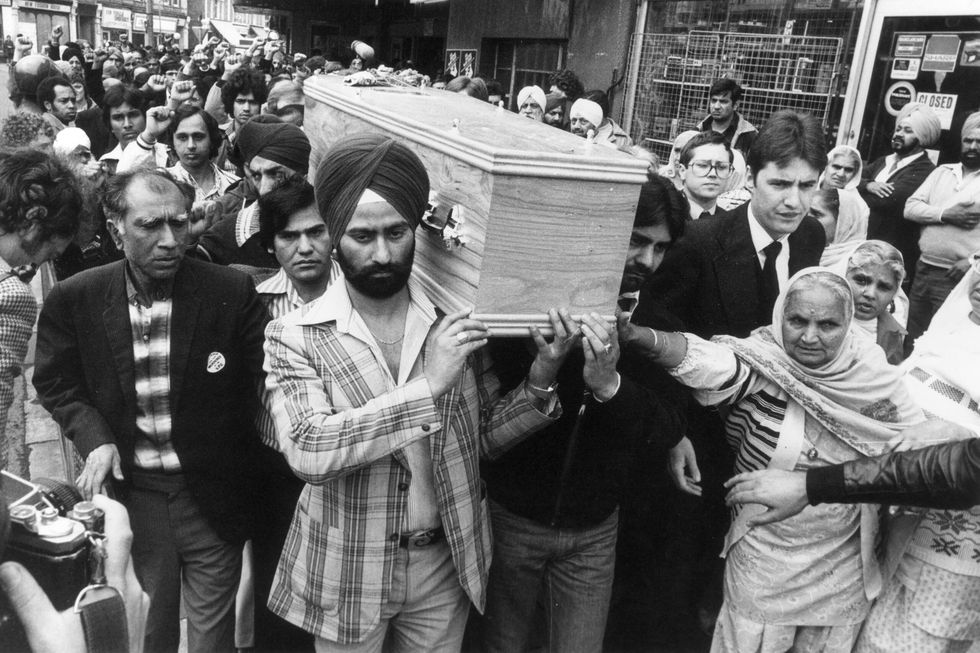

Their comments follow a landmark series on Channel 4, Defiance, which tells the story of how south Asian and black people fought right-wing extremists in running battles five decades ago, and how the police conspired with racists.

Veteran anti-racism and civil rights activists said that the difference in 2024 is that people of colour, whose parents and grandparents were immigrants, are enabling and fuelling hatred towards vulnerable communities, especially migrants.

The journalist, Yasmin Alibhai-Brown took part in anti-National Front (NF) demonstrations in Southall, in west London, where the series mainly focused, at that time.

“It's worse now, because our people are doing it [being racist],” she told Eastern Eye.

“Back then, I don't remember a single black or Asian person using this rhetoric or doing anything other than opposing what was going on.

“We now have these chamchas (hangers on), collaborators, that's what gives it legitimacy.

“Their place in hell is a thousand times worse, as I imagine it, than for the [Nick] Griffins and the Lee Andersons of this world because they know what happened to Pakistanis, Indians, East African immigrants when they came here.

“They are sitting here telling you lies that we were all received so beautifully, so warmly.

“Their narrative is, ‘This is such a generous country, but let's hate these new bastards.’

“They are the worst sort of collaborators, and when people tell me that you don’t believe that diverse people should have diverse opinions, I say they can have diverse views, but they do not have the right to betray their own history.

“Our causes are demonised today, and permission is given to racists to behave as they wish, because they're [racists] so hurt, because they're the forgotten people.

“This narrative of forgotten people, is, in my view, a highly dangerous one.”

National Front

Since the 1950s south Asians have settled in places such as Southall, Tower Hamlets in London, Bradford, Manchester in the north, and Leicester and Birmingham in the Midlands.

The series showed how white people felt they were being forced to leave their homes to make way for the new arrivals.

Using archive material, the programme makers showed that by the 1970s, the NF had taken hold around England and started to attack and murder south Asians.

Suresh Grover lived in Southall, and he was a leading member of the youth movement which fought the right-wing thugs.

After the riots caused by the NF holding provocative meetings in the town hall, protected by the Metropolitan Police, he co-founded The Southall Monitoring Group, now called The Monitoring Group.

“Politicians continue to pander to racist rhetoric, and this means that the politicians who now pander to that anti-immigration, attacking multiculturalism, are actually the same colour and same religion as I am,” he said.

“They know the impact of the language, they know the power of the language, and they know the pain that they will cause migrants by the language and the political rhetoric they use.

“The lesson that we haven't learned, which makes a massive impact not just on the Asian communities, but the rest of BME [black minority ethnic] communities is that we've never, properly dealt with the problem of institutional or state racism.

“The incubator of popular violent racism is actually state racism and the policies that it advocates, with the politicians using language worse than the period in 1970s which drove me to look at racism.”

The civil rights activist told Eastern Eye that today’s south Asian Britons have become “atomised”, divided along the fault lines of religion and caste.

He said the politics of colonial empire mixed with modern day Indian Hindutva [Hindu extremism] were making matters even worse.

“There are people in the 70s 80s 90s, etc. who've had these dehumanising views about each other, whether they were Hindus, Muslims, or Sikhs.

“When you look at the roots and patterns of racism that exist in Britain directly as a result of our colonial experience, there were sections of the community that did not want people to unite and blamed other religions.

“Today we have politicisation of religion, in India, in Pakistan, in the US, the growth of the far right and the rhetoric are really competing to develop far right politics in this country at a global level.

“You have the RSS [Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh] and Hindus on social media, which is now a much more powerful, destabilising weapon to attack Pakistan or Muslims in Leicester and vice versa.

“So, it's a different period when there is a serious crisis in how society’s run and the far right try and use the politics of division and dehumanisation to fill that space that exists.”

Aaqil Ahmed grew up in the north-west of England, and he told Eastern Eye how his market trader father would have to scrub off racist graffiti and worse from his pitch.

“It doesn't take a genius to figure out that other nations are trying to influence members of parliament and how people vote, we've seen it with Russian interference,” said the former Channel 4 commissioner and ex-head of religion at the BBC.

“There's no getting away from it, the politics of the BJP are, whether you want to use words like infiltrated or whatever, are now on the streets of the UK.

“And that's something that we should keep an eye on – none of us want the politics of the BJP that we see in India to be replicated on the streets of Britain.”

Equally, Hindus in Leicester have told this newspaper that Muslims are to blame for starting the disturbances in the summer of 2022.

Two inquiries are being held into the cause of religious tensions in the city.

Nuanced racism

It is important that politicians understand the nuances of racism and division on today’s Britain, he said.

But Ahmed contends that division among south Asian communities were sown by stealth.

“When I think about when I was a student, there was a political blackness, and that's how we used to talk about it [race politics],” he rationalised.

“Then when I first started working in the early 1990s, I remember, we were still Asians, we weren't Muslims or Hindus.

“But it was changing, and in my mind, one of the first programmes I worked on was a documentary about riots in Blackburn in 1992.

“That was when we were starting to have conversations about Indians and Pakistanis, not Hindus, they were all Muslims, but there was that whole kind of split.

“Over time, then we started talking about, Sikhs and Muslims fighting in Slough or Birmingham, and bit by bit, we've seen that erosion.

“So now we're black and Asian, then we became Indian, Pakistani, Bengali, and now it's Muslim, Sikh, Hindu.

“This wasn't the world that we grew up in, where we were fighting those battles, and if we have to fight those kinds of battles again, it's better to be doing it from a unified position than it is just trying to fight for your own corner.”

Defiance producer, Rajesh Thind, is well-aware that his films have struck a chord among today’s British-south Asians, old and young.

Since the series aired on Channel 4 last week (8 to 10 April), thousands have taken to social media to contribute to the discussion and comment that airing this story was long overdue on British television.

But he thinks the splitting up of south Asian communities started long before the terrorist attacks on the Twin Towers in New York in September 2001.

“I'd say that by the late 1970s, early 80s, the Conservative Party was attempting to separate out those parts of the Hindu and Sikh communities which were beginning to show themselves to be entrepreneurial,” he said.

“They were thinking, ‘Well, if we can bring those over to the Tory fold, then that allows us again to play divide and rule.’

“And I'd suggest that, the idea that was born in the minds of Tory strategists 45 years ago is now playing out.”

‘Colonial sandwich’

But how does he explain the rhetoric used by children of immigrants who became politically powerful and, like Suella Braverman who declares publicly, in front of a room full of the Conservative Party faithful that she would “love to have a front page of the Telegraph with a plane taking off to Rwanda, that's my dream, it's my obsession”?

“I'm always trying to look through these things through the lens of history,” Thind said.

“As someone whose mother was born in East Africa, the thing I noticed about Braverman, [Priti] Patel and [Rishi] Sunak, what I actually see in them is less about the history here in Britain, and more about the history of imperialism and colonialism.

“I describe it as the sandwich colonial system that was in East Africa, in which you had a white colonial elite at the top, fairly discreet, mostly just interested in raising tax revenues and sending them back home to Britain.

“Then you have a black, African mass, and in the middle, there's this Asian middle class, and a deal is done, whether it's spoken or unspoken, but a deal is done in which the whites colonial elite say, ‘Look, if you play the game, keep your mouth shut, don't get involved in politics, you'll get to be rich and wealthy, and it'll all be fine.”

The columnist, Yasmin Alibhai-Brown was born in Uganda, and she was a teacher in Tower Hamlets during the height of racial tensions in the UK.

“It's not worse in the sense that they're [right wing extremists] not roaming around like they were then,” said the civil and human rights activist.

“But since Brexit, freedom has been given to racists to say whatever they want to spout at people they don't want.

“Certainly, the tabloids and the right-wing press are always on their side.

“We now have a culture where white racists have the right to behave as they wish, but the victims of racism, they must not protest, may not complain too much, because then they're accused of being woke.

“The war on woke is a very sinister development.”

Young Asians

For the former Channel 4 commissioner and head of BBC Religion, Aaqil Ahmed, one thing the series has done is to wake up the current generation of south Asians who have not been told about the struggles of their parents and grandparents.

“We brushed it under the carpet,” he told Eastern Eye, “but a lot of people are now looking at this and thinking about well, that's what kind of went on, people actually did affect change, and those people that we look at now who are a bit older, actually have done those things.

“The kind of the campaigning that had to go on, the kind of anger that had to be shown, the kind of injustices that had to be endured.

“I think it's really important that people understand that's part of their heritage.

“One of the things that I think really jumps out when you watch it, and I think it jumps out to a younger person watching it, is that moment that we hear when people refer to themselves as being black.

“That political blackness has gone and also the fact that you had Muslims, Sikhs, Hindus, Bengalis, Pakistanis were all campaigning on the same things and not being a separate kind of entities.

“That's a shock for a young person now, who is living in a silo world within various different cultures, and particularly when they're of Asian culture, and probably can't come to terms with evidence, so maybe it's a wakeup call for them.

“But maybe it's a reminder of actually the shoulders of the giants that they stand on.”

The episodes are a warning for today’s Britain, said those who spoke to Eastern Eye, of vital lessons from the past to educate our future.

“We can't afford to be complacent, we have to make sure that we diminish the impact of racism, and I have come to one conclusion that will never ever be eradicated,” said the head of The Monitoring Group, Suresh Grover.

“The system doesn't want to eradicate it, and if you want to eradicate racism you have to reinvent the system that we were living in.

“I wish we could change the system, and I would support the changing the system.

“The way to look at is, from the time of colonialism to the present, we’ve made progress otherwise we'd be diminishing the contributions made by people who fought against racism and colonialism in the past.

“But actually, that progress is not constant, because unfortunately politicians, leaders have allowed the far right to gain much more influence than they then they should have.

“I fear for this country with the consolidation of the far right, not just amongst white communities, but amongst Asian communities.

“That actually is the new period that we're confronting in Britain today, and we have to fight against racism, it becomes one struggle at the moment.”

'I was a witness to state terror'

The journalist and columnist, Yasmin Alibhai-Brown was a teacher in east London. She joined protesters in Southall on the fateful day that anti-racism activist and teacher, Blair Peach, was beaten to death by officers from the Met’s special patrol group, the SPG.

“I saw attacks by the SPG with my own eyes. They would kick a young boy, pick him up from the scruff of his neck and say, ‘Right, you're nicked’, and then he would be charged with assaulting the police.

“As it got more violent, a couple of us ran along the residential street. A family opened the door quickly and let us in and hid us for nearly seven hours.

“They put their little children at the door, so whenever the police would pass, the children were told to wave sweetly and smile.

“That's how they protected us, and it wasn’t very safe. Later, we sneaked out and hopped on a bus and went home.

“It was state terror against the people at the time, and I witnessed it, and I couldn't sleep for weeks after that.

“I kept having nightmares that they would turn up at the door.”

'We're written out of history'

Aaqil Ahmed is an award-winning programme maker. He was an executive commissioner for Channel 4, and he became the first non-white head of religion for the BBC. His father was a market trader in the north-west of England.

“I always remember when I used to work with my dad on the holidays, we used to have to open up the hoods, and we had to cover all the racist graffiti.

“We had to get things out of that'd be left behind, they’d [NF] had broken into the huts, and defecated and all sorts of stuff.

“That was what we did because you just got on with it.

“So, for young people, there'll be a better understanding, and a better grounding for them.

“Often our stories are forgotten about or we're not cool or trendy, or we're not important.

“We're written out of lots of stories, we're written out of history.

“The first world war, the victory wouldn't have happened had it not been for those millions of soldiers from the Indian subcontinent, and we're written out of this.

“What Defiance has done for a number of different generations, particularly for that young generation, is that it has given them some kind of grounding in something that they can relate to.”

The National Front and me

Skinheads and the National Front are part of my childhood in Coventry, writes Barnie Choudhury.

Like most Indians, my father came to the UK first and in 1969 he sent for my mother and the five of us.

At four and a half, I was the youngest, so I grew up in 1970s Britain.

Next door was an old man who kept himself to himself.

I soon learnt that the smells coming from his house was that of boiled cabbage, a far cry from ours with its fragrant curries – you know the reason why white Britons called us “smelly bastards”.

It’s funny how on this year’s Masterchef, a white man has so far beaten two south Asians by cooking better curries.

When I went to infant school, my mother tells me that on my first day I walked hand in hand with an African-Caribbean girl, as if we were united in our colour.

Don’t get me wrong, it wasn’t a particularly hostile school.

In fact, black played with Asian who played with white.

Indeed, aged seven, a beautiful blond girl asked me to be her boyfriend.

Not knowing what that meant, I instinctively said no, because I sensed my father would vehemently disapprove.

This young, white angel cried when I said no, and I felt sad.

Outside school it was a different matter when it came to different races mixing.

It seemed that everyday my Indian friends and I would have to fight off white children, with cropped hair, who went “P*** bashing”.

They’d be singing a little racist ditty about P-bashing to the tune of Scotland the Brave.

It went something like this:

Hark when the night is falling,

We’ll go P*** bashing,

Cos we’re so brave in killing,

Let’s do the deed.

Racial divides

Most often we’d be outnumbered, and they would punch and kick until we were bleeding.

But more often than not, we returned the favour when we found one of the skinheads who through sheer stupidity wandered the streets alone.

Unfortunately, or perhaps, fortunately, we stopped short of making them bleed or breaking skulls and bones.

Even then, we realised we didn’t want to be moronic cowards.

I started secondary school in 1976, and that’s when I immediately knew things were worse.

The racial divide was so obvious.

During break, south Asians would try to play soccer on the school fields, while white teenagers would commandeer the football knowing the teachers would do nothing.

I remember one thug – short black cropped hair with dock martens, the uniform of the National Front - intent on bullying me.

Once, his mates held me down while he laid into me, kicking me in the head.

After that my elder brother made sure that I had his big Indian friends escort me to and from lessons, as well as home.

My personal security lasted six months, and then suddenly the bullying stopped.

I learnt later that a group of Indian lads found my nemesis and did to him what he did to me.

Job done.

By 1979, under Margaret Thatcher’s Britain, Coventry became even more racially divided and violent.

The city’s two-tone ska band, The Specials, immortalised it in their number one hit, Ghost Town.

But it was April 1981 when we hit rock bottom.

A group of skinheads chased 20-year-old Satnam Singh Gill through the city centre and kicked him to death.

I heard later that his crime was to be seen walking with a white girl.

In our communities, we felt the police did little to protect us, blind to the possibility of racism or racial attacks.

It was a case of immigrants having it coming.

Murders

That May thousands of us marched through Coventry, black, brown and white united in fighting the National Front.

By the time we reached Broadgate in the city centre, the skinheads were there shouting “sieg heil”, the cry of Adolf Hitler’s Germany.

To this day I find it confusing that these imbeciles would mimic the very enemy their fathers and grandfathers gave their lives fighting.

As ever, the police protected the thugs, and as they tried to kettle us in all hell broke loose.

I remember police horses driving straight at my brother, our friends and me.

Behind them officers with their batons raised striking anyone left behind.

Later that day, in a gurudwara, eating roti and daal, we told ourselves that we had made a difference.

If only.

In June, skinheads murdered Dr Amal Dharry, a family doctor who volunteered for a homeless charity in the city, someone who took saving white lives to a different level.

Things are different in 2024.

Britain remains a wonderful place, this is my home, and I’ll support England ahead of India in sport.

But I am sick and tired of having to prove my patriotism.

I am sick and tired of having a pit in my stomach every time I hear about an attack, afraid it will be some brown or black man.

And I’m sick and tired of politicians, leaders, and colleagues of colour who demonise immigrants just to prove they are whiter-than-white and more extreme to fit in and win votes.

Today, we don’t see as many running battles based on the colour of our skin.

Racism today

But that doesn’t mean Britain is racism free, as some of our politicians of colour would have us believe.

I still call myself politically black.

I still call myself a British-south Asian.

But I still know we, south Asians, have changed beyond recognition.

I hate the fact we are no longer as one.

I hate that we distinguish ourselves along the fault lines of our religion and caste.

Most – and I mean 99.9 per cent – white Britons are fantastic, and they do not base their decision on skin tone.

But some will never accept that we, people of colour, are here by invitation, because our parents did the job they wouldn’t do.

In fact, because of Empire, we were British citizens, such is the lack of their education.

They are the ones who think that white Europeans fleeing war have more of a right than brown-skinned men who fought alongside British soldiers to rid evil regimes.

And we, south Asians, have played right into the hands of those clever white racists who knew all along that they could divide us, and rule us, by giving us baubles, playing on our vanity.

These south Asians proved Orwell right when he wrote, “All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others.”

In other words, they decide history, and we abide.

An aerial view of the British Steel Scunthorpe site on September 13, 2024. (Photo: Getty Images)

An aerial view of the British Steel Scunthorpe site on September 13, 2024. (Photo: Getty Images)

Mehakdeep Singh,Sehajpal Singh

Mehakdeep Singh,Sehajpal Singh

FILE PHOTO: A general view shows British Steel's Scunthorpe plant, in Scunthorpe, northern England, Britain, March 31, 2025. REUTERS/Dominic Lipinski

FILE PHOTO: A general view shows British Steel's Scunthorpe plant, in Scunthorpe, northern England, Britain, March 31, 2025. REUTERS/Dominic Lipinski