ASIAN women are being urged to carry out regular checks of their breasts and attend screenings after a study found they were delaying in presenting with breast cancer symptoms – which means they are more likely to die from the disease than their white counterparts.

A study commissioned by the charity Breast Cancer Now found that lack of awareness, cultural barriers and myths and misconceptions are among reasons why Asian women are being diagnosed with cancer at a later stage, and as a result, they have fewer treatment options.

“Our insight found that while breast cancer incidence rates are lower among ethnic groups compared to their white counterparts, they are more likely to die from the disease when they have a late-stage diagnosis,” Manveet Basra, head of public health and well-being at Breast Cancer Now, told Eastern Eye.

The study also found more than half (59 per cent) of white British women check their breasts weekly or monthly, but that figure drops to 31 per cent among Asian women.

One in five Asians (18 per cent) believes “there is no need for them to check for breast cancer”.

However, the corresponding figure among white British women is six per cent.

And for those who do check their breasts, Asian women had the least knowledge of breast cancer – with only two-thirds knowing five or more symptoms. In comparison, about nine out of 10 white British women know of five or more symptoms.

Iyna Butt was a fit and healthy 30-year-old woman. In 2015, during a home workout, she had an itch on right breast and felt a hard lump – it turned out to be a tumour the size of a golf ball.

She told Eastern Eye, “I never self-checked my breasts. It was purely by accident I discovered the tumour. If I hadn’t worked out that day I may never would have found it and I may not be here.” Butt was diagnosed with an aggressive form of stage 3 breast cancer. She said she lost all her hair “in one shower”.

After a year of treatment, including chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and a single mastectomy, she is in remission.

“I had no family history of breast cancer, no underlying health conditions, so it came as a complete shock – something I never expected would happen,” she said.

Coming from a strict British Muslim family of Pakistani heritage, Butt said checking her breasts wasn’t on her radar as it was never spoken about in her family or community.

“South Asian families are generally brought up in quite a modest way in many respects,” said the HR director at a design and build business in Reading.

“Speaking about your body’s system is something you didn’t do, and especially coming in a Muslim family it definitely wasn’t something that was brought up.”

Breast Cancer Now’s study surveyed almost 600 women, half from an ethnic minority background; it also conducted 12 focus groups and liaised with three GPs, two community nurses and one practice nurse. “From our insight we found that particularly fear and fatalism are specific barriers to women from ethnic minorities talking about breast cancer,” said Basra. “For some women, they felt maybe it was something they had done wrong, and their diagnosis was specifically down to that.

“Some people within certain ethnic groups thought it was something that actually affects (only) white women.”

One woman who spoke to the charity said: “The Indian community, especially the elderly, find it hard to talk about cancer. They feel they may be looked down on, feel ashamed, and embarrassed. There will also be a lot of gossip.”

The report found that twice (28 per cent) as many women from ethnic groups believe there are myths about breast cancer in their community compared to white British women (14 per cent).

One woman told Breast Cancer Now: “People will run away from that family as they think it is hereditary, and then no one will want to marry into that family.”

Another said: “When you have cancer some people think it’s your fault. That you have not been looking after yourself. That you have been living an unhealthy life.”

Breast Cancer Now is working to remove some of these stigmas by having volunteers, some who have had breast cancer, to go into communities and places of work to speak about cancer and help spread awareness.

“We have volunteers within our organisation from some of these ethnic backgrounds, who are working with us to really empower other women to talk about their diagnosis and share their own stories, as a way to build confidence and enable other women to be able to come forward and talk about this,” said Basra.

“Our case studies from ethnic groups each provide a different perspective and lens on what it was like for them and some of the learnings they’ve experienced from their own diagnosis as a way of educating and informing others – so that they can help to break down some barriers for other women.”

Dr Farzana Hussain has been a GP in Newham for over 20 years. The borough, where 43.5 per cent of the population are Asians, has the worst cancer survival rate in the country.

Her practice has around 5,000 patients and she told Eastern Eye she has seen first-hand that Asian women are less likely to go for cancer screenings.

All women over the age of 50 are offered appointments to have a mammogram screening every three years.

“If I look at the statistics for my practice, only two thirds of my women go for the screening – one third are not going. And this is despite our best efforts in the practice in reminding people about the importance of screenings – but one in three women is still not going for their mammogram and that is quite high,” Dr Hussain told Eastern Eye.

Breast Cancer Now’s survey backed-up Dr Hussain’s insight as it found that almost a third (30 per cent) of ethnic minority women are either not aware or don’t know about the programme compared to nine out of 10 (89 per cent) white British women who are aware of an NHS breast screening programme.

A third of Asian (38 per cent) women said they did not know the benefits of breast screening.

Dr Hussain, who was named GP of the year in 2019, revealed she had never been taught how to check her breasts. “I am 49 and I absolutely have to say this, I have never been taught by anybody how to do a breast check. I haven’t seen enough public health messaging about it. I only know about it because I’m in the medical field,” she said.

“So I think public health and we, as healthcare providers, have a lot to do about getting that message out.

“I never knew about this and I don’t recall ever really hearing a lot. So I think whatever public messaging we’re doing in the NHS is not enough.”

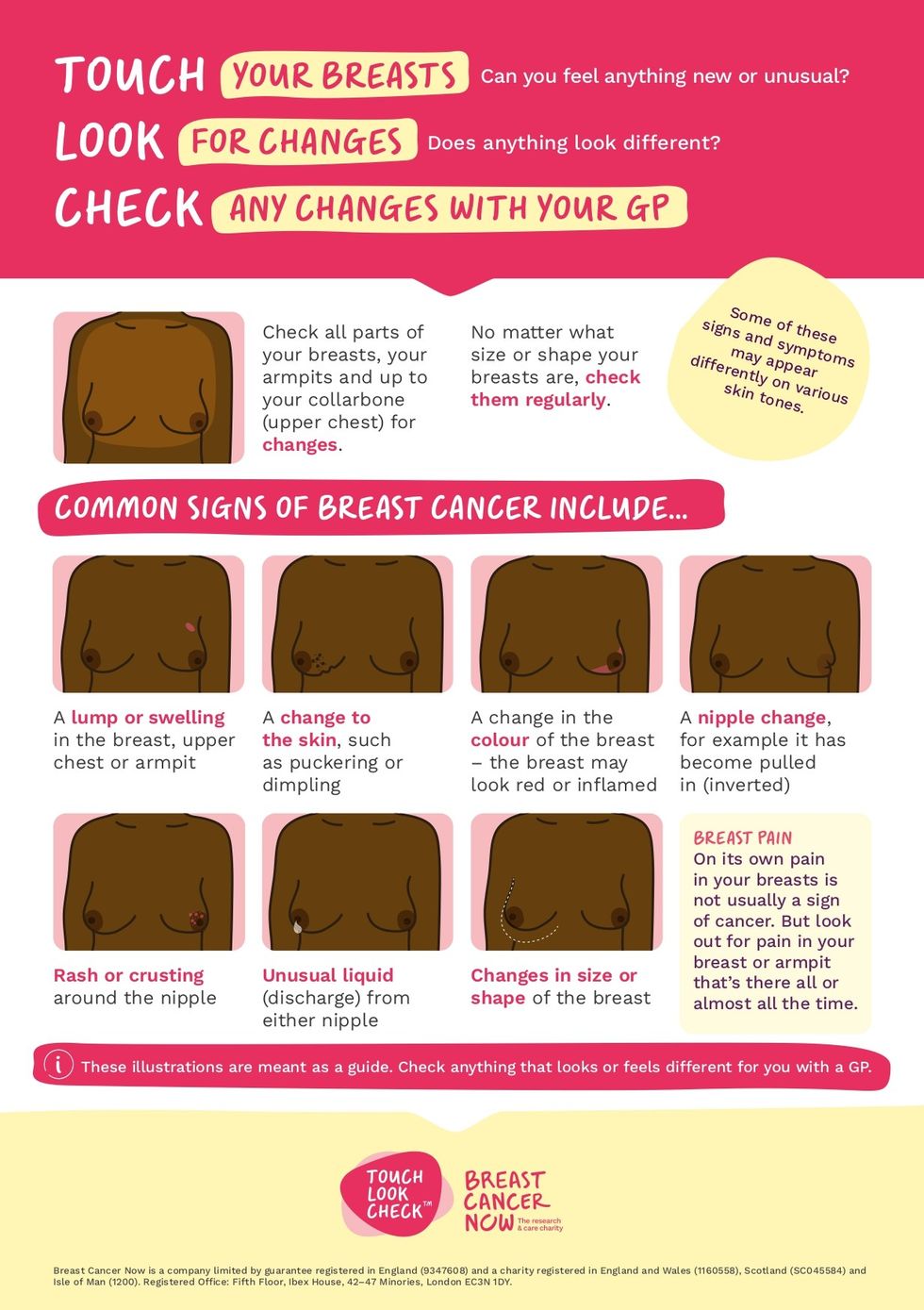

Basra highlights: “There’s no special way to check your breasts and you do not need any training. It’s really important to get used to checking your breasts regularly to be aware of anything that’s new or different for you. Making this part of your routine – such as when showering, putting on moisturiser or getting dressed – can help you to make it habit of a lifetime.”

From her experience Dr Hussain said there are several barriers preventing women from ethnic minority communities from accessing relevant information, attending breast cancer screenings and accessing treatment.

“I do find the understanding that we should self check our breasts is lower in our South Asian women,” she said.

“They don’t know we actually recommend that when you’re going in the shower, you should check yourself for any lumps. If you don’t know what you’re checking for, your cancer is going to present much later if you have it.”

She added that there is a recognition that different communities have different needs which leads to barriers and, as a result, a lack of awareness and education. “Language is a major issue,” said Dr Hussain. “Sometimes women are concerned that when they go to have their breast screening, will somebody be able to explain things to them because their English might not be the best or their first language.

“There is a concern about the person or the team doing the breast checks – are they female? Will I have to show intimate parts of my body to a male? I’m lucky where I am as we are an all-female team who do the screening, but those things are not always well advertised.

“For our south Asian communities, it’s also not just about the language, it’s about the culture and making it more sensitive. If we do a video – for example – that is very explicit, I’m not sure everybody would want to watch that. So it is how we actually convey those messages in a culturally appropriate way.”

Iyna shares the same sentiment as Dr Hussain and called on better representation in campaigns to raise awareness for breast cancer. The mother-of-one revealed she had been in contact with a number of breast cancer organisations but said she refused to be part of their campaigns due to the fact she would either have to be topless or in lingerie.

She said, “There needs to be more modest campaigns and representation of ethnic minority communities. We don’t see ourselves on flyers, on adverts, on social media campaigns for these big charities. “When you don’t see yourself, you don’t think it happens to you. You don’t think it can touch you, it’s not relatable.

She added: “When you switch on your TV, and you see a campaign with a topless female, being in a south Asian family, you’re more likely to change the channel, you’re not going to sit there and continue watching it with your kids around, parents, siblings etc.”

Basra agrees that organisations need to do more work to target ethnic minority communities. “We need more targeted programmes and tailored approaches for communities to be able to talk to them in a way that’s culturally appropriate that takes into account some of the sensitivities,” she said.

As a result of their research, Breast Cancer Now said it will develop material in different languages to support women for whom English might not be their first language. To tackle the issue of Asian women not attending their breast cancer screening appointments, videos and leaflets will address questions such as what happens during a breast screening, its purpose and whether a female doctor will

be present during a mammography.

For those that can’t read or write, especially the elder generation, there will be audio information in different languages on breast cancer awareness.

Basra said working with community groups and places of worship was an important step in understanding some challenges faced by people and then responding to them.

She added: “Earlier this month we did a session in Cardiff, which was both in English and Urdu so that it could appeal to the target audience there – minority ethnic communities.

“This is something we are expanding on and developing this year, so that we can be adaptable and flexible to everyone’s needs. We hope to reach out to much larger audiences.”

Dr Hussain spoke of a positive experience she had at a mosque in Tower Hamlets. “I go to East London Mosque in Tower Hamlets once a week. It is a big mosque with a big women’s area. They were doing a cancer awareness programme for both men and women, talking about how important cancer is or cancers. I thought it was really good to be doing that in the Muslim community where people will be listening rather than just doctors talking about it. So I think we need to do more of

that within communities."

Kareena remains an unstoppable forceInstagram/ kareenakapoorkhan

Kareena remains an unstoppable forceInstagram/ kareenakapoorkhan