The national treasure tells us how she beat up racists, and why she is optimistic for the future for Asian artists

by Barnie Choudhury

Meera Syal is ferociously funny, intensely intelligent, and she has an edgier side that shows off her campaigning spirit for equality.

Let’s get one thing clear. Her home life with Goodness Gracious Me co-star and husband, Sanjeev Bhaskar, is not one punchline after another.

“When we're in the mood, yes” she said with a twinkle in her eyes and huge smile on her face. “Other than that, it's grumpiness, and who's taking out the recycling and whatever you get in any domestic setup.”

Syal is speaking to me in front of a virtual audience for the Asian Media Group and University of Southampton’s inaugural fireside “Pioneers Project” chat. She is on top form.

The art polymath – she writes, acts and sings – has been excelling in her profession for more than 30 years.

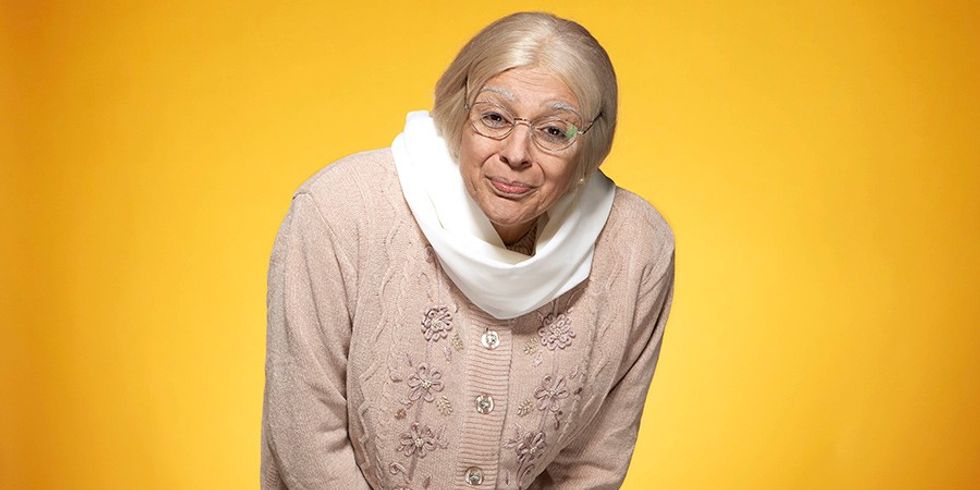

Syal has just returned from shooting a Disney film in Canada. Spin will be the organisation’s first movie where the central characters are south Asian. In a world exclusive, she spoke about her role as a grandmother championing her granddaughter’s passion for being a DJ mixer.

“I was told think Barbra Streisand meets Bollywood, and I was thinking I’m there, I’m there,” she said. “It's a very classic Disney tale, one of those heart-warming, family films,” she said.

“They run a restaurant. The young girl is very talented musically. She wants to be a DJ. Her father isn't happy with the idea mainly because his wife, who has died, sadly, was a wonderful musician, so it's too painful for him to see his daughter follow the same path as the wife he misses so much.”

Diversity on and off screen

What made the difference for Syal was the diversity of not only the cast but the crew – the director is Manjari Makijany, the talented Indian film maker.

“It's like finally, finally, we've been waiting for this for a long time. It seems to me that there is a genuine need and desire to do diverse stories that are not just the obvious ones which they were in the 70s 80s. I think now it's much more about what are the universal stories that we all share that are filtered through a specific cultural lens. Interestingly, the more specific and accurate you get culturally, the more universal story becomes.”

She warms to the diversity theme.

“It was just so great to be on a set where you weren't going, ‘Do you know what? We are actually a Hindu family, and that's a Muslim icon on the wall, that's a bit of the Quran, that might not work.’ A number of sets I've been on where that's happened? ‘No, no, actually, they're Sikhs and he wouldn't be called Iqbal Khan, sorry.’

“I didn't have to do that because here was an Indian woman directing the film. So, it's not just about diversity in front of the camera, it's so important that we are represented behind the camera. In the crew, in the writing, the production, and in the direction, that's what makes the difference to authenticity.”

Childhood challenges

Syal grew up in the Midlands, the former mining village of Essington, her family being the only Asians. Her parents, economic refugees said the actress, embraced village life, and she described her childhood as idyllic, “cycling with mates, scabby knees, a real tomboy”.

This was the late 1960s, where the nearby MP was Enoch Powell, infamous for his “rivers of blood” speech. The family experienced racism, but not from villagers, who were white, working class, and were “a great community”.

“There are a lot of stories that your parents don't tell you, especially when you're little, because they don't want to upset you. But the racism, the no Irish, blacks and dogs notices, the going for a job interview and suddenly finding it's mysteriously filled. They went through all of that, and I did used to ask them do you regret coming, and they've always said no, absolutely not, because you kids would never have had the opportunities in India that you got here.”

But here is the huge surprise, and the first time she has ever spoken about it. The young Meera would often have to use her fists to escape her out-of-village, racist, abusers.

“When I got to senior school, it was a long, long way, and I had to take two buses,” she remembered. “If I missed that bus, I had to walk through a council estate, and I did miss the bus quite often. But I learned really early on that if I looked like a victim and I behaved like a victim, it [the abuse] got worse.

“And if I walked with confidence, and if I said stuff back and occasionally had to use my fist sadly, it got less. I thought you know what, if I'm going to survive here, I really got to stand firm and stand tall, just got to front it out, no matter how scared I am, because this isn't going to go away. And I can't apologise for the space I occupy.”

Syal never told her parents about any of the racism she faced because she did not want to worry or bother them.

One of a kind

Her parents supported her decision to go to the University of Manchester to read drama, where she got a double first.

This was hugely significant for Asian immigrants who wanted their offspring to become doctors, dentists, pharmacists, engineers and lawyers.

But it was a lonely time for Syal, the only south Asian on her course.

“I don't ever remember seeing another brown face in the arts department at all, plenty in the medical school, obviously. But actually, it gave me a massive advantage because I suddenly realised that a lot of the material I was creating, people have never heard before.

“I was so used to being the only one in the room all the time, so in the early years, you feel this sort of madness, with the loneliness, leads you to think am I really mad trying to do this? I don't see anybody out there like me, how can I get a job? Who will hire me? Who will think whatever I write is relevant or interesting? Will they get it? All of these things.”

Of course, she did succeed, getting a three-year contract at London’s Royal Court and going on to produce hits such as Bhaji on the Beach, which Syal wrote.

“I ended up doing theatre really for my first decade. It was a long time before I got into television because I was lucky enough to hit the London theatre scene just this time where there was a real welcoming of diverse voices.

“In theatre, I was being offered roles I would never ever play on screen, and still probably [would] not. A Peruvian millionaire is in Serious Money, a deaf-mute girl in the 17th century in Birthright at the Royal Court. So, I did my first four or five years with the Royal Court, a whole plethora of parts that had nothing to do with race.”

Breaking barriers

Syal believes the theatre was where the barriers about casting were being broken down, while screen and television have spent decades trying catch up.

“Television have been hung up on whatever people think reality is. So, we can't have a black president, that wouldn't be real. They said 25 years ago. That's not reality, it's more real to have an Asian woman playing a victim of domestic violence than a lead cop, so this is the part we're going to offer you.

“But actually, television and screen should not just reflect what we think the status quo is, they should also be aspirational, they should also show us the kind of reality we are working towards.”

Syal said there is research which shows the effect of being aspirational.

“Before Obama was elected, there were three or four major films in which a black president was cast. And at the time, people said, far fetched, isn't it? But then they did some research and directly linked those big blockbusters to the changing of people's attitudes and accepting a new kind of reality. They said the casting of these films actually helped Obama get elected, because suddenly people saw a reality that they thought could be possible.”

The constant complaint among British black Asian minority ethnic (BAME) actors is that they have to go to America to make their mark.

“I think it's still true, unfortunately,” said Syal. “If you want to get a script onto British television, there is probably only about six people that have the power to commission. That is a tiny, tiny, little bubble.

“In America, it's the land of immigrants, and they have a completely different view of diverse casting anyway, and the industry is much bigger. It's very sad. There's been a real brain drain, one of the things that makes me really sad actually is particularly South Asian female representation.

“If I think about Bhaji on the Beach, it was way ahead of anything that America has done. If I think that Goodness Gracious Me happened way before anything America’s ever done. It feels like we started it here, but then the Americans took the baton and ran right past us, because they were willing to go, we want some new diverse voices, and we don't see you in a specific box, so here we are, what stories do you want to tell? That's not happening here.”

Lazy racism

What happens in television and films, she said, is a lazy form of racism.

“It is getting out of the quota system in your head and actually [stop] thinking that there's only room for one Asian show a year, one Asian star, one Asian drama, one Asian comedy and to take that label right off it and go what's good, and not to worry about who's not going to watch it who is going to watch it.

“Audiences are much smarter than they give them credit for. Audiences will watch what's good and they don't really care what colour the people are that are in it. They really don't. They just want to watch good stuff.”

It was the 1990s hit comedy series Goodness Gracious Me which propelled Syal into the nation’s consciousness, even introducing the Indian word for underpants [chuddis, as in “Kiss my chuddies, man!] into the English lexicon. It was, said Syal, a coming of age which showed Britain that south Asians had arrived and did have a sense of humour.

More success followed with the international Emmy-award winning The Kumars at No 42. The fact the comedy did not win the BAFTAs (British Academy of Film and Television Arts) in 2003, 18 years ago, is something which still rankles.

“Sanjeev and I were both nominated for Best Performance, but not as actors but against hosts. So, I was up against Paul Merton, and it was just that sort of a lack of care. The Kumars was never on the same level as Have I Got News for You. It was an acting job, it happens to be a chat show, but why is it not in a sitcom category?

“Why have you put us up against a host? And there's still a sadness about that, actually, for both of us, because we thought that was probably our one opportunity and we would have been the first south Asians to get a BAFTA. Those kind of things disappoint you, looking back.”

Stepping up

BAFTA has been criticised for not recognising BAME talent, but with the arrival of new chair, Krishnendu Majumdar, last year, Myal is hopeful things will get better.

“BAFTA’s stepped up in the past year, and the head is now Krish, who's a fantastic, fantastic advocate, quite rightly, for diversity. So, Krish has implemented quite a few changes, changes to the membership, changes to the voting procedures. Lots of things have gone through the last year again, in the wake of Black Lives Matter, but also the BAFTA being so white row.”

The good news is that the BBC’s Mrs Sidhu Investigates should return for a second series on Radio 4, with the hope that it could transfer to TV. And Syal returns as Granny Kumar and her chat show on 10 February.

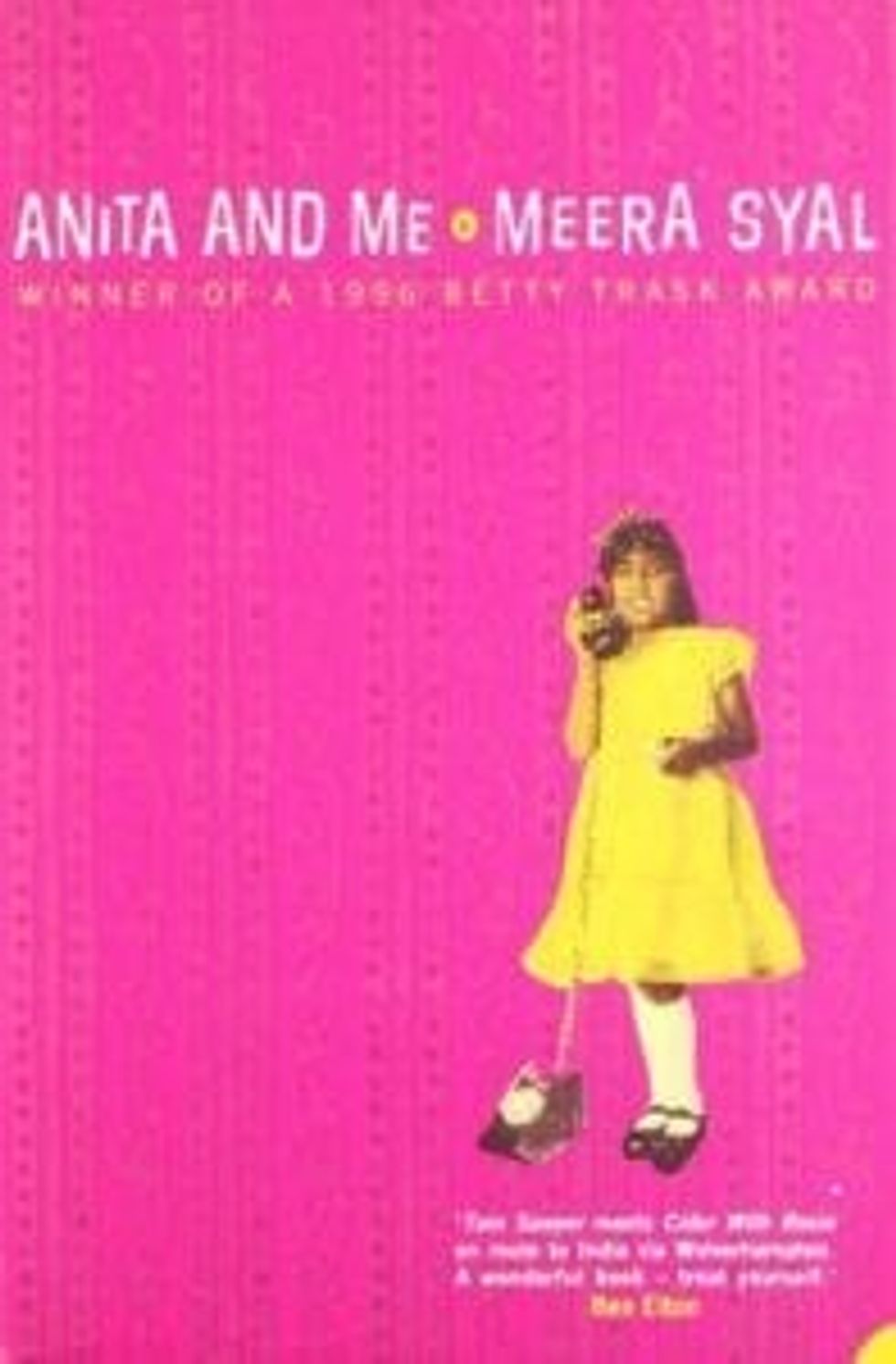

Syal is, undoubtedly, a pioneer in her field and generation. Her semi-autobiographical novel about her childhood, Anita and Me, was not only made into a film, but is now a set text in some GCSE English exam boards.

Pioneers

The AMG-University of Southampton Pioneers Project, she said, was an important part of British history.

“We’re making history as we go along, and it's not written down. We have not been written into so much of British history, and we're just finding that out now. I'm writing a historical drama with Tankia Gupta, and one of the characters in it is an ayah. We've been in this country for hundreds of years, but actually trying to find the records, and trying to find particularly the personal stories, the narratives of those people.

“It's so sad when there's nothing there other than a statistic saying, ayah arrived on dock, died, blah, blah, blah. There’s nothing else, nothing of who the ayah was her dreams or hopes or fears, what happened to her. So, a lot of our history has not been recorded. If you're not recorded, you're forgotten, so this is really important.”