Revealed: Top judges being taught how to stop Asian and black lawyers from progressing

South Asian lawyers are demanding to know why judges are being taught how turn down candidates applying to join the judiciary.

Documents obtained by Eastern Eye reveal that senior high court justices, and others, who are asked to give their secret opinions of a solicitor or barrister applying to become a judge now have a template for rejection.

Judges, solicitors and barristers have condemned the so-called “secret soundings” process, used by the Judicial Appointments Commission (JAC) to select and promote justices.

“What is the necessity of having a crib sheet?” asked the secretary of the Society of Asian Lawyers (SAL), Attiq Malik.

“Telling people, guiding assessors on how to turn people down? We have never seen that before in any other industry. Why is it necessary for the judicial appointment?”

The association will be meeting the JAC this month for talks, but it is unhappy about our revelations.

“It raises serious concerns in terms of fairness, and justice, particularly as we see the soundings are coming from what we would call the house of justice, the courts, the decision makers of justice in this country in every area of law,” continued Malik.

“If people are going to be judged, they should be judged on merit on a process which is objective and measurable, and not something which is subjective, and done behind closed doors.”

SAL is concerned about the lack of “transparency or accountability” on these processes.

Malik told Eastern Eye, “How do we know if what is taking place is truly fair and just, in a climate where there are concerns of institutional racism across various industries in the UK to then have secret soundings and secret conversations and subjective measurements being adopted, as opposed to objective ones for who is good enough to be a judge?

“This raises the concern of how do we know that there is not an element of discrimination at play in this secret sounding and your decision making?

“How do we know that race is not an ingredient that is affecting those decisions, or religion or any of the other protected characteristics that may exist under the Equality Act?”

Secret soundings

The “officially sensitive” document reveals the way judges are advised to choose candidates.

Oddly, it seeks views from those who may not even know the candidate.

“If you turn to others with perhaps a deeper, more recent or more developed knowledge of a candidate, do please include their input in your response,” the document states.

“We welcome it. And please show them the guidance – we are keen to make life as straightforward as possible for all who help us.”

The document stresses that no-one will ever find out what they have written, promising to use data protection laws.

The document makes it clear, “Let me reassure you; responses to statutory consultation are completely confidential and no candidate will be given details of what you write. The JAC is scrupulous to adhere to the current data protection legislative and regulatory scheme.”

But one south Asian judge said, “This is outrageous nonsense, although references are thought to be confidential, anyone can ask to see their reference.

“It’s worse now than 20 years ago when I was rejected, the lord chancellor wrote to me explaining why and who wrote what about me.

“Hiding behind data protection shows how scared the JAC is. Their discriminatory practices will be found out.”

The document gives an example of how candidates can be turned down.

“I do not know this candidate’s work well but they did have personality difficulties, (as did others) with colleagues. They seemed very fragile and after a short time they asked for an assignment. The candidate has continued to sit in the chamber where they spent much of their time working for an alternative lead judge”.

“On the basis of the above, I consider the candidate UN-APPOINTABLE.”

One south Asian judge exploded in anger when they read what referees were being asked to do.

“Just read that comment,” they said. “They don’t know the candidate’s work well enough to pass comment, yet they do. They admit others had the same personality difficulties. They diagnosed the candidate was fragile. Then in bold and capital letters they concluded they were unappointable.

“This is being held up as an exemplar. Tell me, how is this fair? How does this meet the Equality Act?

“This makes a complete nonsense of the whole process. Here we are with a ludicrous statement, in secret, no come backs, no scrutiny, no checks, no balances, and yet because they are a senior judge their views count? Come on, don’t make me laugh. No wonder they want to keep it a secret and never let the public know. It is unfairness at the highest level.”

Lack of diversity

Eastern Eye has been campaigning for more than a year for a root and branch investigation of the Judicial Office and its practices after we revealed a culture of bullying, racism and sexism in the judiciary.

As a result of our campaign, last month the justice select committee questioned the chair of the JAC, Lord Kakkar.

We pointed out to the committee a paragraph in the “Diversity of the judiciary 2020 statistics report”.

It claimed, “overall, compared to the pool of eligible candidates, success rates for BAME candidates were an estimated 17 per cent lower than for white candidates (not statistically significant)”.

But analysis by Eastern Eye revealed that in 2020, a white candidate was almost 2.5 times more likely to be “recommended for immediate appointment” than a non-white applicant, which judges we spoke to is “statistically significant”.

We asked the justice committee to comment on this, and we have shared with it the document we obtained.

So far, the committee has not responded, and the JAC too has refused to comment.

But in a statement, a spokesperson for the Judicial Office or judiciary said, “The document you quote is not trying to stop potential judges progressing; it is trying to ensure that any relevant evidence – positive and negative – is available to selection panels alongside all the other evidence considered in the process.”

During the justice committee hearing in July, the JAC’s chair made great play of its Judicial Diversity Forum (JDF) and the Judicial Diversity Forum – Officials Group Meeting (JDFO).

They were mentioned 23 times during the hearing.

This included an answer from Lord Kakkar that the forum had been restructured when asked if the JAC looked at barriers to progression.

“[in] addition to the principals meeting together senior officials from all of those organisations meet together regularly. They look at barriers. They look at questions.

“For the first time last year, they achieved publication of a combined set of statistics that look at statistics from the professions and professional progression, statistics from the judicial appointments process and statistics from the judiciary itself.”

Diversity forums?

But exactly what do the forums discuss, and how do they measure outcomes?

Using the Freedom of Information Act, Eastern Eye was able to find out what the forums discuss.

We passed the document to several judges, both white and non-white, to get their views.

“From what I’ve seen, these forums are simply talking shops,” said one judge. “They do nothing, and it gives the Ministry of Justice and the Judicial Office ammunition to say move on, nothing to see here, move on.

“It’s a box-ticking exercise where they mark their own homework, allowing them to say, look we’re doing our best, and it isn’t our fault that these ethnic people can’t make it.

“They’re unrepresentative racially, and the one person of colour is a man who’s never had to put together a legal argument and has no clue about the bullying and racism we undergo on a daily basis.”

Another south Asian judge was even more scathing.

“The thing is there is no diversity but simply having a brown face is not enough,” they wrote.

“We need people who are known to have a) no ambition to rise further b) are fearless. Simply a brown person rewarded for agreeing is worse. That’s what we have.”

One senior judge said the minutes were “written in jargon”.

“Either the minutes are selective, or the meetings are very brief,” they concluded. “The emphasis is on controlling uniformity of message and public posture of all the constituent bodies.

“This inhibits the scope for the Law Society, as representatives of the most disadvantaged group, arguably from departing from the party line.

“There’s mention of intersectionality, of professional associations, social networks practice areas and geography as cumulative factors. But there’s no will to explore it.”

Another said, “The JDFO officers’ meetings focus on massaging the messaging noting the professions are asking for more granular data.

“The note in the recent JDFO minute that the Judicial Office have suggested ‘consideration needs to be given to whether the benchmark for diversity should be the pool of candidates rather than society itself’.

“This is truly a 1970s approach. If we daisy chain this approach to judging diversity performance down through the professions, the universities, and schools, just looking to see if we are making the right selections because the proportions reflect the pool, we will find the benchmark much easier to achieve.

“In the end it will require no action as it is only at the bottom that we are failing when we will conclude probably that there is nothing to be done and society is to blame.”

‘Abandoning responsibilities’

One described the meetings as a way of the judiciary abandoning responsibility of a huge, age-old, problem.

“[They’re] saying that the judiciary need not represent society, that we should write off the years of failure to achieve that goal, and that we should move the goalposts so that the judicial statistics will aim low and pass the buck to the professions.

“It is a proposal to turn the clock back. Those who appear as clients in court are not ‘drawn from the pool of candidates’.

“Their faces and lives and experiences are drawn from society and so should our judges.”

The Law Society is part of the diversity forum, and its former president, David Greene, attended some of the meetings.

He told Eastern Eye. “Our concern was not so much that this is just a talking shop, more the aim its taking is incorrect and misguided.

“The vital issue, is what is happening with that junior level? Why is it not progressing? There could be lots of reasons.

“It may not be a racial prejudice point but simply a way in which the exams are done, which call on much more on advocacy skills.

“In some ways, it might be institutional discrimination with the way in which the next level up is taken.”

Greene is also representing a crown court judge, Kaly Kaul, in her legal case against the Ministry of Justice (MoJ), the lord chancellor, Robert Buckland, and the lord chief justice, Lord Burnett.

Kaul’s case centres on claims that she was bullied and mistreated by members of the senior judiciary after she complained about “disrespectful, discourteous, unprofessional, and rude” barristers who appeared before her.

In an unprecedented and landmark concession, the MoJ, agreed that the Judicial Office owes a duty of care to judges.

“In the modern world, it's important that no one's above the law,” said Greene. “So far, as the judge is alleged to have breached the law in the conduct with another judge, I think most judges would actually have accepted that the ministry did have a duty of care.

“It does give members of the judiciary the confidence to be able to assert rights in front of the court and in front of the employment tribunal.”

Judges we spoke to were also concerned that the FOI response clearly showed that for a forum which claims to examine and champion diversity, the JDF did not have one single person of colour who was legally trained.

Defending the indefensible

A spokesperson for the Judicial Office defended what some judges describe as an “indefensible slight which proves they don’t have a clue what they’re doing and care nothing about racial equality or diversity”.

“The purpose of the Judicial Diversity Forum is to increase diversity in the judiciary by bringing together the relevant bodies and professions,” said the statement.

“It is made up of the leader of each constituent body, the judiciary, the MoJ, the JAC and the legal professions, showing how seriously each personally takes the issue of diversity.”

One judge told Eastern Eye, “Your work is important because everyone thinks we’re privileged.

“If only they knew the bullying, sexism and racism which exist in our profession, they won’t believe it.

“And if we’re under attack, if we have all this white noise so that we’re on anti-depressants and contemplating suicide, how can we dispense justice to those appearing in front of us?

“The public doesn’t understand that we have to follow edicts passed down from people who may put career before justice.

“We need to be able to serve justice to those appearing before us, and we’re being hampered at every step.”

Analysis

Judges are made from barristers, solicitors and chartered legal executives.

Eastern Eye has continued to analyse the data available, and we have examined the figures and how the government chooses to interpret them.

Sometimes the messaging is confusing.

For example, in the 2020 Diversity in the judiciary report, the authors make a startling admission:

“In practice, most applicants for judicial roles have more than the minimum experience. For court and tribunal posts requiring five years or more experience, applicants have on average around 15 years’ experience.

“Among those with 15 or more years’ PQE (post qualification experience), BAME individuals constituted 14 per cent of barristers, 12 per cent of solicitors and three per cent of chartered legal executives.

“For court and tribunal posts requiring 7 years or more experience, applicants have on average around 20 years’ experience.

“Among those with 20 or more years’ PQE, BAME individuals constituted 12 per cent of barristers and nine of per cent of solicitors.”

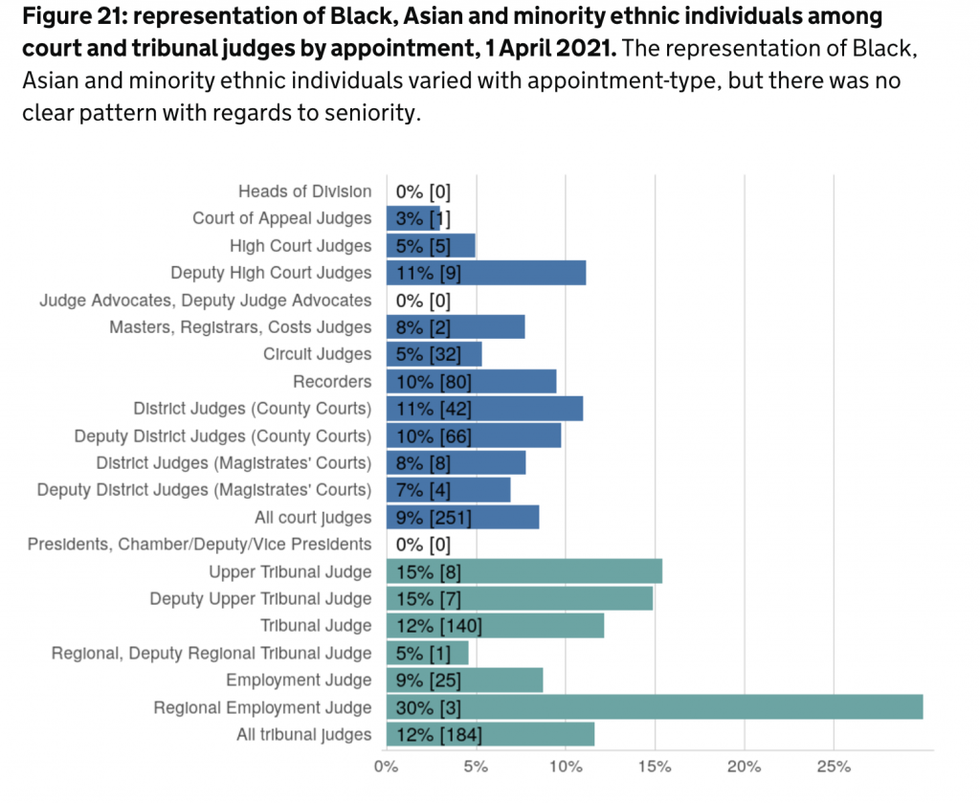

The judiciary knows that in some divisions, non-white representation was “generally lower for the more senior appointments (e.g., Court of Appeal, High Court and circuit judge)”.

As with 2020, this year, in some categories, such heads of division, a judge and deputy-judge advocates, there is not one single person of colour.

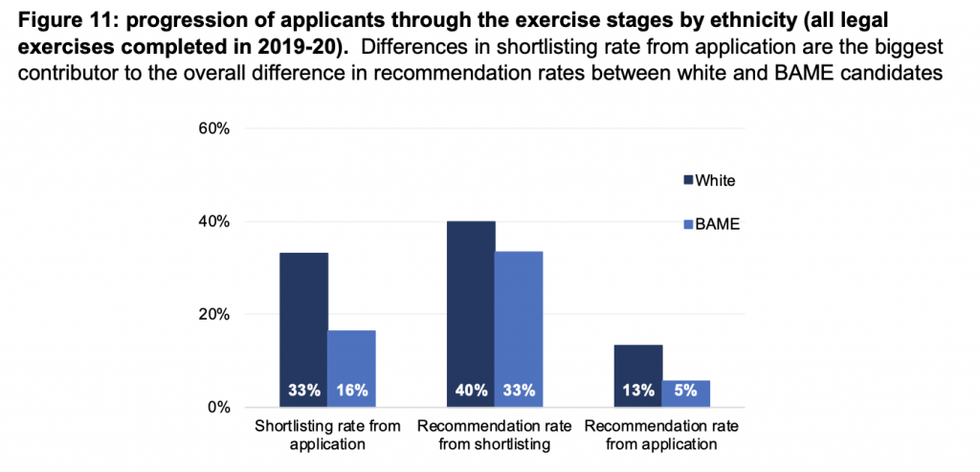

This report also highlights the disproportionate nature of white success compared to non-white candidates.

It showed that white applicants are more than twice as likely to be shortlisted than those who are non-white.

Worse, non-white candidates are almost three times less likely to be recommended for a post compared to white applicants.

The report also concedes that, “Considering the representation rates at different stages in all cases the proportion of BAME applicants was higher than in the corresponding eligible pool, but (except for circuit judge) the proportion of recommendations that were BAME candidates was then lower than among applicants.”

Attiq Malik, from the Society of Asian Lawyers, believed social class was a factor in the inequality of appointment.

“Traditionally, what we saw was that people from certain more privileged backgrounds would become barristers, and people from less privileged backgrounds would become solicitors, so already we have a class divide within the legal industry.

“So, how can we have a judiciary which is fair, in its processes of judging the populace, if the judiciary is made up from a pocket of the populace, which is a minority and does not reflect the nation generally.

“Tied into that, you then have race because of the socio-economic context that surround people from certain racial backgrounds where they live in the UK, what the position is on the structure of society.

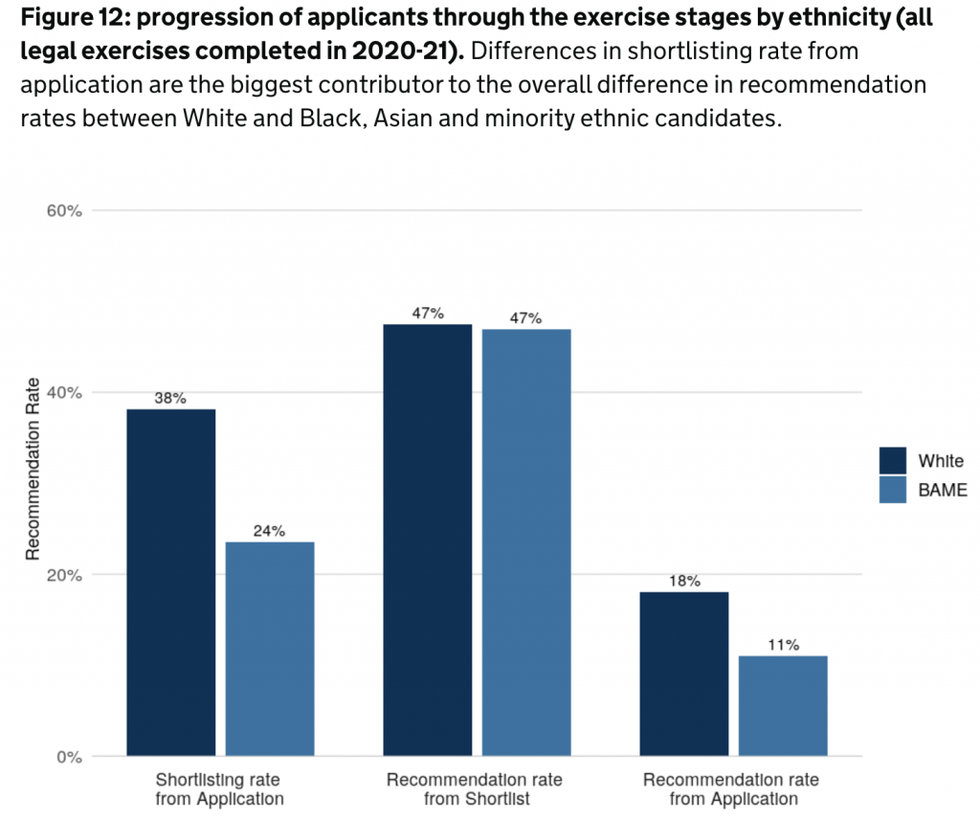

The latest figures suggest a slight improvement.

Source: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/diversity-of-the-judiciary-2021-statistics/diversity-of-the-judiciary-2021-statistics-report

This still shows a 14 per cent gap in being short listed and 1.6 times less likely to be recommended to be appointed a judge if you not white.

“If you come from certain backgrounds, and English may not be your first language, and the other hurdles that you have to go through in life, without having to battle this when you are a capable professional,” said Malik.

“You've done the hard yards, you've done the work. But simply because you're from a certain class background or racial background, you're still left at a disadvantage in modern England, in 2021. This is shocking to say the least.”