By Barnie Choudhury

THE UK government must stop “weaponising race” and using it as a political tool to further its political agenda, a panel of experts has told Eastern Eye.

The experts, who were taking part in a virtual debate, unanimously concluded that Britain today was more divided about race and racism than during in the high-water mark of 2012, the year of the London Olympics.

“When you look at Nigel Farage, some of the utterances of (home secretary) Priti Patel and (prime minister) Boris Johnson, about making immigration the fundamental centre point for Brexit, that has given a lot of people who ordinarily would not mouth racist things, a passport to say these things,” said Sailesh Mehta, a barrister and part-time judge.

“I’ve noticed in my profession, as well as in general in society, that in the last two or three years there has been a hardening of racism and racist opinion that we didn’t see a few years ago.”

The panel was responding to the government’s latest race repot which concluded that Britain was no longer institutionally, structurally or systemically racist.

Report condemned

The report’s conclusions were roundly condemned by the panellists.

Nero Ughwujabo, a former special adviser to former prime minister Theresa May, said she set up the Race Disparity Unit to tackle the “burning injustices” felt by Britain’s non-white communities.

“When that report [under May] was published, it was very clear there were persistent inequalities,” said Ughwujabo.

“If this was to make a different claim to what was already made by the disparity audit, it should have given the explanation as to exactly how we have arrived at that position, and I don’t think it does.

“That’s where the challenges are, and that’s where I think people are questioning whether this report was intended to be a truthful, accurate representation of what’s actually happening on the ground.”

Like many, the journalist, writer and professor, Yasmin Alibhai-Brown, felt Downing Street had already made up its mind about what it wanted the report to say, and brought in people who would deliver its views to head the group.

“This report has given the prime minister exactly that,” Alibhai-Brown said.

“If you started saying there is no sexism in this country, if girls and women only took care of themselves a bit better and stop the sense of victimisation, there would be outrage.

“So, there is a political agenda, which maybe some of the panel members didn’t know, and that was to deny not just institutional racism, but all kinds of racism.”

Sanjay Bhandari, the chair of Kick It Out, football’s anti-racism group, believed that the debate needed to focus on the recommendations.

“When you actually look at the recommendations, quite a lot of them mirror other reports,” he said. “Why don’t we implement the recommendation from the eight other reports?

“What it brings to mind for me is The Smiths [Manchester rock band] song, What Difference Does It Make? And, actually, what difference is this gonna make? And what difference do all the other eight reports make?”

What the panel unanimously agreed was that Britain remained institutionally systemically and structurally racist.

“Normalised nepotism”

Alibhai-Brown was Britain’s first non-white national newspaper columnist. She contended that her profession needed to wipe out systemic inequalities.

“There’s a kind of normalised nepotism [in newspapers],” she said. “The reason we are in the state we are in is there have been no systems in place to create equal chances for those outside those circles.”

It is not just black and south Asians who are excluded, but white working-class people as well, she added.

“You have to have gone to private school, you have to have gone to Oxford or Cambridge, you have to have been in those circles. So that is what systemic, institutional racism is.

“You look at the way people enter the profession and then rise in it, and you realise it is wrong, unfair, and immoral. And you make it a much fairer, neutral system. That’s beginning to happen now.

“It’s very simple to me. If there was no systemic racism, we would have more people in the top hierarchies of every profession. We exist at the bottom. We’re not moving up. Why is that?”

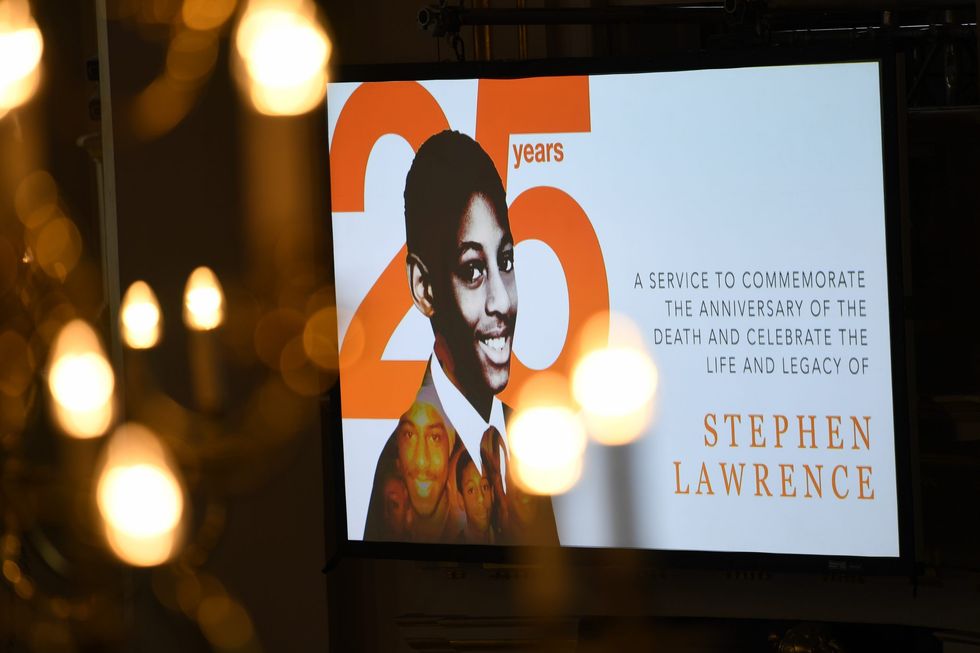

In 1999, Sir William Macpherson concluded that the Metropolitan Police was institutionally racist when it investigated the stabbing murder of the black teenager, Stephen Lawrence.

More that 20 years later, his definition that institutions could be “unwittingly” racist remains a bone of contention.

“I suspect that my colleagues or judges, if they ask themselves, ‘am I racist’, that the answer will be ‘no, I don’t think I am’,” argued Mehta.

“But if they then ask themselves, why is it that our profession in the last 20 years has been almost entirely made of white, upper middle-class men, and the further up the judicial structure you go, the numbers from public schools these individuals come from, then you get an idea that this must be structural. It cannot be the case that the top judges in the Supreme Court and the court of appeal can only be created by three or four of the country’s top public schools.

“It must be, therefore, a structural problem. I’m willing to concede that it may be unwitting, although I suspect that there may be a ‘witting’ element to it, a knowing element to it as well.”

Tick box exercise

Bhandari, who was part of the Parker Review into the ethnic make-up of boardrooms, said the danger with all investigations is that they would lead to a tick-box exercise when it came to tackling the lack of racial diversity and inclusion.

“The principal beneficiaries of that are Asian women, because you tick two boxes to get in as a non-executive director,” he said. “That’s the place where people go to fill their criteria and say, ‘actually, yeah, I’ve kind of done diversity, because we’ve got this person that fulfils some criteria.’”

He argued that racial imbalance was caused by what he called “majoritorial bias”, where the system favoured those who were the majority in an organisation.

What institutions needed to do was the examine what he called the “egregious statistical anomalies in the system” and to conclude something was going wrong.

“The biggest statistical anomaly in football is that 10 out of 4,000 professional footballers are Asian,” said Bhandari.

“You have to unpack that as to why aren’t kids getting into academies? What are the stereotypes that are applying, what are you recruiting for? Who’s doing the recruiting? What are they thinking?”

His conclusion was that children as young as eight were chosen to join an academy based on the stereotype of how they would develop when it comes to pace, strength and power. Scouts believed these traits cannot be taught, while technique could, he said.

“That explains two things. It explains a positive stereotype that black people experience, which is why they are disproportionately positively impacted in that they are over-represented in academies.

“It also explains why Asian kids are disproportionately impacted in that they are perceived as not being strong. What it means is if Xavi [Simons], [Andrés] Iniesta or [Lionel] Messi were born Asian in the UK, they would never have been professional players because they would not have made it through the academy. Because they are small, they would have been perceived as weak..., as their diet not being helpful.

“Someone would have said their parents wanted them to be a doctor or a lawyer, all of those stereotypes would have been applied to them because they are being applied today. So, you have to get into the weeds of understanding where the blockages are.”

Lack of political will

The biggest hurdle, said the panel, was that the recommendations from all the race reports commissioned by various governments have not been implemented.

Ughwujabo believed implementation came down to political will.

“There are specific areas which I think were low-hanging fruits for this particular commission,” he said. “One of them would be the ethnicity pay gap. We’ve seen progress in terms of gender with the gender pay gap, not least because it started a national conversation about gender.

“Also, companies responding to question their existing systems and structures that disadvantage women in the workplace and do something about it.

“So, the expectation for the ethnicity pay gap is that it would have done something similar, and I think that’s one missed opportunity.”

Cosmetic change

The Eastern Eye panel called for parliamentary scrutiny to audit the latest report to make sure the country knew which recommendations had or had not been implemented and the differences they had made.

“Whether intended or unintended,” said Alibhai-Brown. “You have to conclude that all these things are cosmetic. What we’re missing is an alliance of people of different backgrounds coming together and saying, not good enough.”

For Bhandari the answer to tackling racism in institutions came down to those willing to hold their staff to account.

“I think it’s going back to who matters more, Larry Fink [boss of investment company BlackRock] or Boris Johnson?

“It’s because the CEO of BlackRock sends a note out to all these investment companies saying, ‘I’m going to be measuring you not just on quarterly returns or quarterly income, but also on your social and economic impact.’

“So, the best thing that governments can do is get out of the way and let them get on with doing what they’re doing, because that’s where change is going to be driven from. It’s about getting away from the rhetoric and into [asking], what are the solutions that actually work, and focusing on those actions.”

The US base at Diego Garcia

The US base at Diego Garcia

Anti-immigration activist Stephen Yaxley-Lennon, known as Tommy Robinson, gestures before arriving at Folkestone Police Station in Folkestone, Britain, October 25, 2024. REUTERS/Chris J Ratcliffe

Anti-immigration activist Stephen Yaxley-Lennon, known as Tommy Robinson, gestures before arriving at Folkestone Police Station in Folkestone, Britain, October 25, 2024. REUTERS/Chris J Ratcliffe