A former MP has called on a British university to investigate claims of racism made by 75 south Asian students.

Eastern Eye has seen a letter to the vice-chancellor of Leicester’s De Montfort University which makes serious allegations of discrimination and racism against the Indian learners.

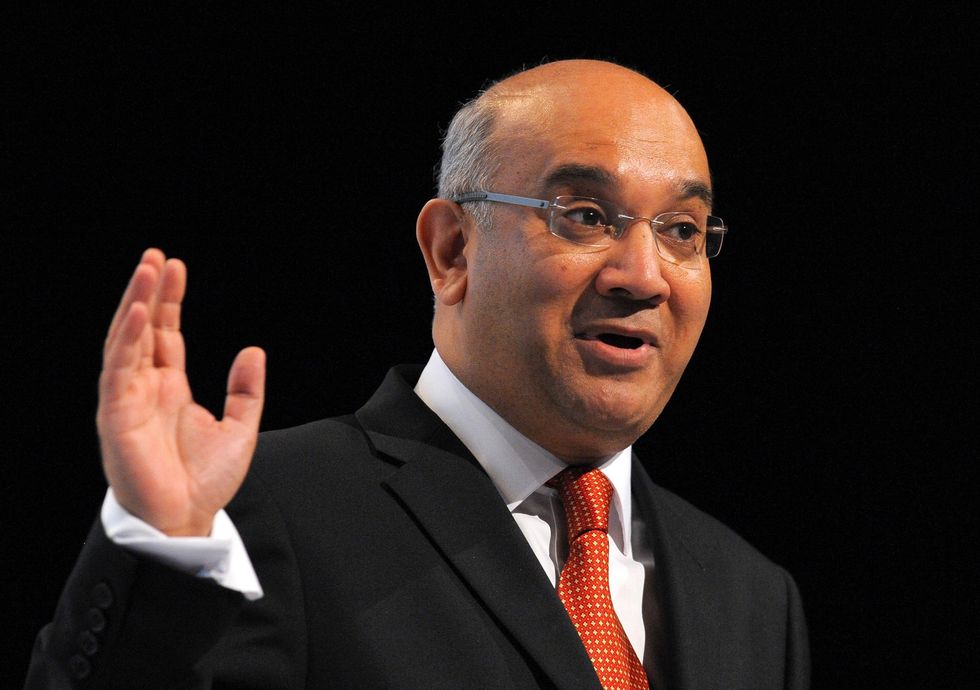

The communiqué is from the former Leicester East MP, Keith Vaz, who chairs the Integration Foundation.

The former Europe minister said his foundation “provides citizens and in particular diaspora communities, with access to decision-makers and enables individuals, organisations, and communities to understand issues of process and governance”.

He sent the letter to the head of the university last month (16).

“I am writing to you today to bring to your attention to an urgent and serious matter concerning alleged discrimination at DMU,” wrote Vaz.

“I have the written consent of 75 of your students.

“If not addressed, this matter has severe consequences for the university, including potential damage to its reputation, legal ramifications, and the loss of trust from prospective students and their families.”

Deprived opportunities

The former parliamentarian, who was elected in 1987, copied the letter to the Office for Students and the Indian high commissioner to London.

“DMU has received around £1.2 million in tuition fees from these 75 overseas Indian students, yet they feel they are being intentionally deprived of the opportunity to obtain their master’s degree,” Vaz continued.

“In all my 34 years of public life, I have not come across a similar case.

“Although, I have written to you and other vice chancellor (sic) on individual cases, I have never written in this way concerning a large group of students.

“I do so because I have huge respect for DMU for its teaching staff and its reputation and I hope by bringing this a matter into you direct attention, there can be a satisfactory resolution.”

Vaz said the students felt they were “targeted” for “discrimination by the instructors who marked their assignments”.

Fair treatment

Eastern Eye understands that the post-graduate learners will not be able to re-sit one module because it is being scrapped and combined with another.

The former minister also wrote that the actions could affect the students right to work in the UK on graduation.

International students can work in the UK for two years once they successfully graduate from university.

“Over the years De Montford University has become a symbol of diversity in education in Europe’s most diverse city,” said Vaz.

“I am proud of its achievements.

“That is why these serious allegations must be investigated thoroughly, independently and immediately.

“In this particular case, every one of the students who have complained have been failed in just one module.

“They have prepared a detailed analysis of what has happened.

“Without a resolution these young men and women will have their lives ruined.

“Research conducted reveals that each overseas student brings in £96,000 in economic benefits to the UK.

“We need them, and we need to treat them fairly.”

Eastern Eye approached the university for comment.

A spokesperson for the university said, “De Montfort University operates clear, independent and rigorous assessment processes, and we strongly refute these allegations.

“Inclusion and fairness are core to our values as an institution and we are confident we have treated students fairly and supported them to achieve their potential, while ensuring that we adhere to the very highest academic standards.”