IN THE first half of the 20th century, Indian immigrants to Africa were often locked into a rigid racial hierarchy. They were conferred benefits not available to local black Africans but held back by their own colours from enjoying the wealth of opportunities enjoyed by the white population.

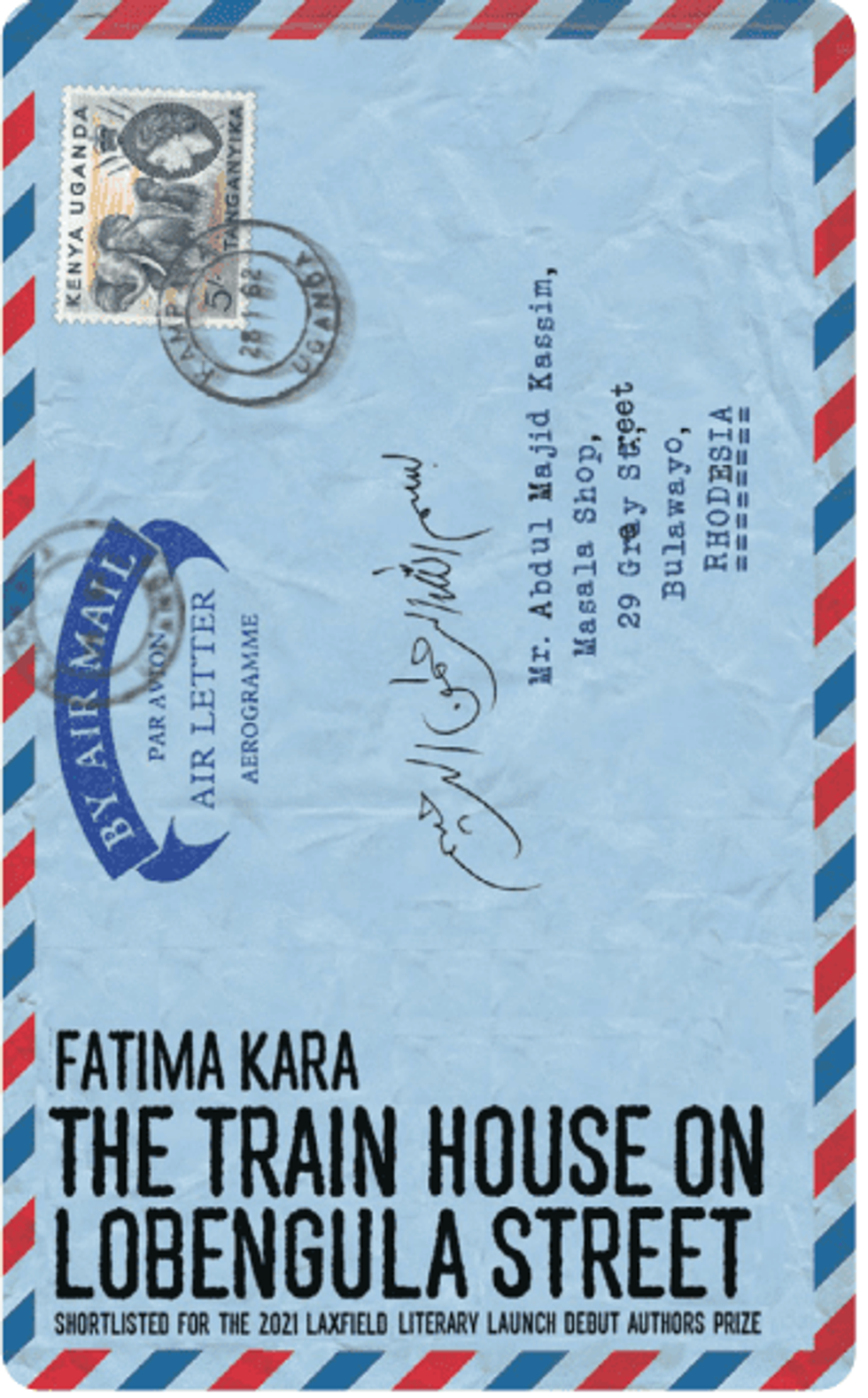

With her debut novel The Train House on Lobengula Street, set to be published on Thursday (6), Fatima Kara delves into her childhood experiences in the Indian community in Bulawayo, Rhodesia (modern-day Zimbabwe) in the 1950s and 1960s.

She tells a detailed story of strong women’s inspiring response to patriarchy and racial discrimination that was extended towards all non-whites. She invokes images of the past and describes the experiences of the Indian diaspora in southern Africa.

Eastern Eye caught up with the Zimbabwean writer living in the US to discuss her compelling new novel.

What first connected you to writing?

I was born into stories. I didn’t go to nursery school. Instead, in Bulawayo, Rhodesia, what is now Zimbabwe, I got an education listening to adults. Their gossip, jokes and scandal nourished my mind and stayed there until I had to start writing it all down.

What inspired you to write a novel?

During my childhood in Bulawayo’s vibrant Indian community, I saw a lot of things that troubled me — like young women travelling to faraway places to enter arranged marriages and Indian men practising civil disobedience against the white police. I couldn’t know for sure what happened to them all, but I wanted to write a version of their stories.

Tell us about your novel?

The Train House on Lobengula Street concerns the interconnected lives of a traditional Indian Muslim family during a turbulent period in Zimbabwean history. It centres on Kulsum, the matriarch of the family, in her search for peace and prosperity against the racial backdrop of colonialism and the patriarchy of her own community.

Is this story based on true events?

The story is realistic in the places it describes and time scale, but it’s a work of fiction. I wove broad social history together with details of my own childhood. I wanted to give a more general impression of Indian life in Bulawayo, as well as tackle universal themes that are common to immigrant communities all over the world.

What would you say was the biggest challenge of writing this novel?

The writing part was fairly easy. The story was ready to emerge from my mind and onto paper. The hard part was what came after. It took years for me to find representation and a publisher as a first-time author, and it continues to be difficult to navigate the changing landscape of ‘what sells’ and self-promotion.

Who are you hoping connects with this book?

I hope the book resonates with readers interested in learning about people and places foreign to them. Like many immigrant communities, this story’s protagonists don’t fit into a single category: they are Indian, coloured, Muslim, and African. Yet their lived experience is universal. How a reader connects with that tension provides an opportunity for reflection.

What is your own favourite part of the book?

It’s clearly an important moment when the daughters of Kulsum are allowed to go to school, something she has had to fight her husband for. But the story chooses to focus on the small joy of buying school uniforms rather than bigger sociopolitical abstractions. One of the girls can’t resist smelling her new shoes and savours the scent of the leather. It’s a reminder that lifechanging moments are experienced through small details.

Did you learn anything new while writing this book?

I wanted to explain everything that I thought would be unfamiliar, and had to learn the power of showing rather than telling. Of course, this is not a new idea. The Russian playwright, Anton Chekhov, said, “Don’t tell me the moon is shining; show me the glint of light on broken glass.” ‘Showing rather than telling’ helps me detach myself from my characters so that they can live and reveal their own stories.

Are there any life lessons we can learn from reading this book?

I shy away from the word ‘lessons’ in this context. I didn’t want to impose as an author, but I think a reader could walk away with evidence of the basic goodness of humanity, even when it is tested by the deep, Jungian shadows of human nature.

What inspires you as a writer?

I want to write stories that have not yet been told, especially those that highlight how we persevere in the face of external and internal constraints.

How do you feel ahead of the book being available for readers?

Excited and a little anxious. I know that once my book is in the public domain, it no longer belongs solely to me. As Roland Barthes has said, “The death of the author is the birth of the reader.”

What can we expect next from you?

I’m working on a sequel but, as Africans and immigrants know well, our stories don’t always map cleanly onto the chronological frameworks that are necessary for digestible plots.

What kind of books do you enjoy reading and do you have a favourite?

My all-time favourite is Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children, followed closely by Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart.

Why should we pick up your novel and read it?

We all tend to prefer stories about what is already familiar to us. That’s why diversity in publishing has been slow to catch on. Some people are risk-takers

and just dive in; others prefer to push their boundaries a little at a time. I think my book welcomes both sorts of readers.