The end of a football season can bring joy and despair. Leicester City fans saw their team relegated on the final day last season. A year on, thousands thronged the streets around the clock tower as the club celebrated promotion straight back up to the Premier League. Hamza Choudhary, who first joined club’s academy programme as a seven-year-old, described it as among the best days of his life. "I've spent so much of my life down here in the city centre.

To be on the bus with thousands of people out, it’s amazing”. Winning promotion will increase Choudhary’s own profile too, as the first Premier League footballer of British Bangladeshi heritage and one of the most prominent British Asian players in his generation to have broken through in the professional game.

A new report this week, Shared Goals, looks at how to maximise the game’s potential for contact, connection and shared identities. The research by British Future, supported by Spirit of 2012, finds that nearly six out of ten adults in Britain have a football club that they support. There is a similar proportion among Asian respondents (55 per cent) as among the population generally. So there is a broad, somewhat untapped, potential for that to grow significantly – in the stands as well as on the pitch.

Actress Meera Syal spoke last week about why she has not been to a football match for 30 years. Witnessing horrendous racist abuse towards a player at her first ever match meant she has never wanted to go back. Her experience will be familiar to many of those who attended matches in the 1980s or early 1990s, whether they were also put off or tried to stick around and push for change.

I was reminded of how much has changed last month when I saw my team, Everton, play at Chelsea. It was not a great result: Everton lost six-nil, though they did bounce back in their following games to secure their Premier League status without too much nail-biting this year. But Chelsea versus Everton would have been rather too risky a night out when I was younger: both clubs had been among those with the worst reputations for racism. Paul Canonville, Chelsea’s first black player, endured racist taunts from a large National Front contingent among the Stamford Bridge crowd. Everton were late to sign black players.

The photograph of Liverpool’s England star John Barnes back-heeling a banana off the pitch became iconic. Overt racist chanting was a common experience when I was a teenager with a season ticket, but I saw that recede sharply from the mid-1990s, challenged by anti-racism campaigns from the club and the fans, and stronger policing too. Today’s Chelsea has honoured Canonville’s status as a club legend, naming a suite in their Stamford Bridge ground after him.

Syal acknowledges those efforts for change but her story reflects the shadow cast by past experiences without a proactive effort to include and connect today. The British Future research finds that most people feel that their local football club is an inclusive place – though the 55 per cent of ethnic minority respondents who feel their local club is open to people from all backgrounds is lower than the 64 per cent for the public, as a whole. Almost a third of ‘armchair fans’ from an ethnic minority background said they were put-off attending live games by worries about whether the atmosphere would be welcoming to people of different ethnicities, faiths or social backgrounds.

The British Future research reports on work with Brentford FC and Huddersfield Town AFC on campaigns to use the power of the badge to communicate their vision of being a club where everybody is welcome. The report proposes new work on an inclusion and belonging index that can help to promote a ‘race to the top’ among clubs to promote that positive vision.

What is most distinctive about football in this country is not the fame and fortune at the top of the Premier League – which can be found among the biggest clubs in Spain, Germany and Italy too. Rather, it is the depth and range of local pride that spans the divisions, as the remarkably large crowds across the divisions and into non-league football at clubs like Portsmouth, Notts County, Bradford City and Southend United show.

Three decades of action to tackle racism in football have given this next generation strong foundations. There are new challenges too. Social media platforms also need to show the red card to racism, so the progress we have made against hatred and prejudice is not undermined. But kicking racism out of football was never only about what we needed to remove; it was also about building the necessary foundations for inclusion. The power of the badge – for club as much as country – is its ability to invite everyone to come together and be part of a shared identity in which we can all take pride.

(The author is the director of British Future)

The Calcutta Club

The Calcutta Club The Bengal Club lawns

The Bengal Club lawns

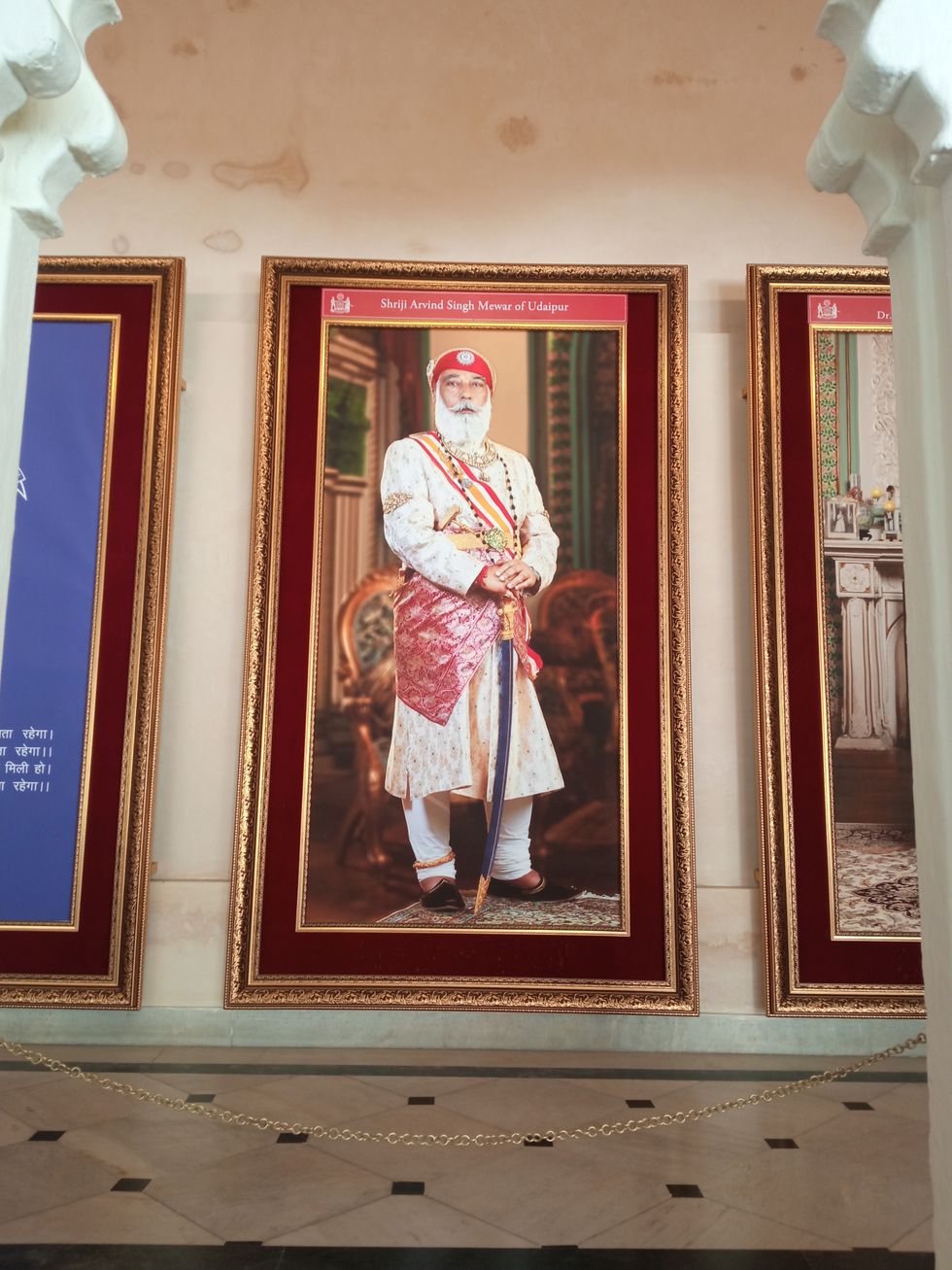

His portrait in the City Palace

His portrait in the City Palace

Pakistani artist Moazzam Ali Khan caught the attention of Bollywood legend Javed Akhtar with his soulful YouTube cover of Yeh Nain Deray Deray

Pakistani artist Moazzam Ali Khan caught the attention of Bollywood legend Javed Akhtar with his soulful YouTube cover of Yeh Nain Deray Deray John Abraham to headline action thriller Tehran

Getty Images for DIFF

John Abraham to headline action thriller Tehran

Getty Images for DIFF

Tikri Border, Haryana-Delhi by Aban Raza

Tikri Border, Haryana-Delhi by Aban Raza Harmz Matharu

Harmz Matharu Abhishek Bachchan in Be Happy

Abhishek Bachchan in Be Happy Devika's soulful vocals shine in her new Punjabi ballad Wisteria

Devika's soulful vocals shine in her new Punjabi ballad Wisteria Indian Idol star Nitin Kumar promises a soulful mix of qawwali, Sufi, and folk music at his upcoming UK performance

Indian Idol star Nitin Kumar promises a soulful mix of qawwali, Sufi, and folk music at his upcoming UK performance Kunal Kamra during his show

Wikipedia

Kunal Kamra during his show

Wikipedia

Swiss-Indian singer BombayMami is making waves with her bold style and sound

Swiss-Indian singer BombayMami is making waves with her bold style and sound Hania Aamir receives a questionable honour in London

Hania Aamir receives a questionable honour in London

A resident in Odessa, Ukraine, as smoke rises from a fire following a strike earlier this month amid the Russian invasion

A resident in Odessa, Ukraine, as smoke rises from a fire following a strike earlier this month amid the Russian invasion

Shweta Warrier

Shweta Warrier Harbans Singh Jandu

Harbans Singh Jandu Aamir Khan

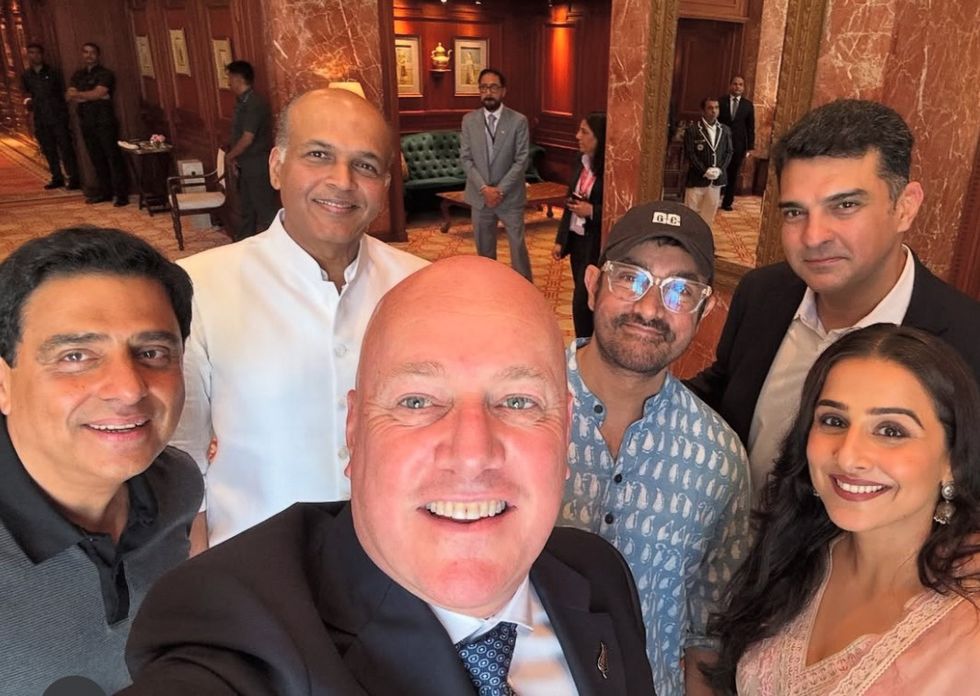

Aamir Khan Ronnie Screwvala, Ashutosh Gowariker, Christopher Luxon, Aamir Khan, Siddharth Roy Kapur and Vidya Balan

Ronnie Screwvala, Ashutosh Gowariker, Christopher Luxon, Aamir Khan, Siddharth Roy Kapur and Vidya Balan Madhuri Dixit

Madhuri Dixit

FBU chief raises concern over rise in racist online posts by union members