HALF a century ago, it was the Ugandan Asians who needed sanctuary. Given just 90 days to get out by the dictator Idi Amin, it was not clear where they would go.

At the height of the Powellite era, some MPs floated hare-brained schemes to send them all to the Falkland Islands, or simply suggested washing our hands of this problem.

For prime minister Edward Heath, Britain’s moral obligation was clear. “It is our duty. There can be no equivocation … They are entitled to come here and they will be welcome here,” he said.

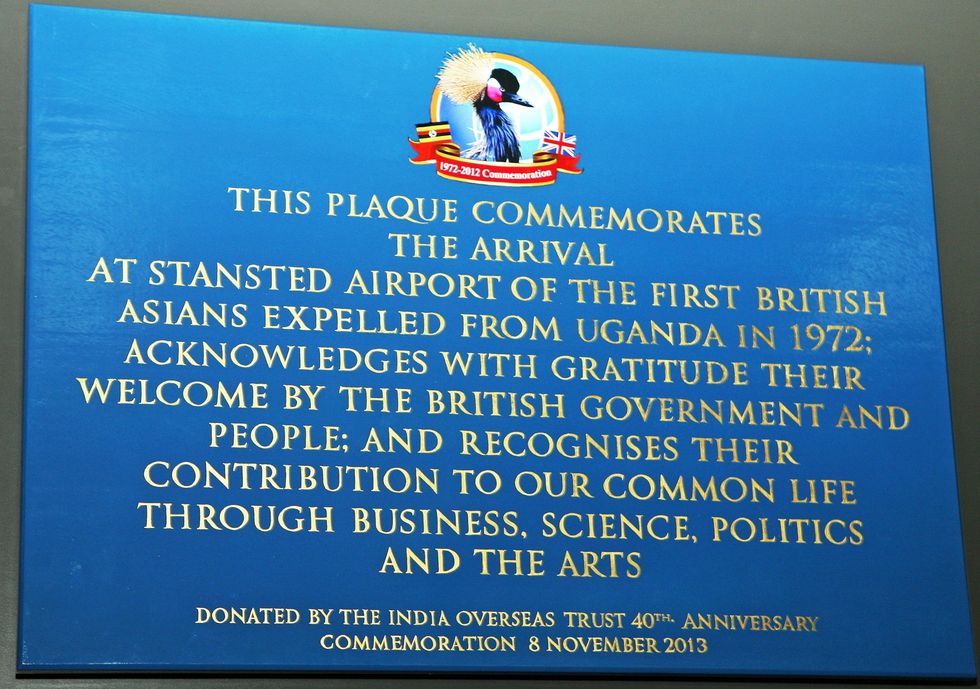

Fifty years later, Mukund Nathwani, a teacher who arrived, aged 23, from Uganda in 1972, says that decision saved his life. He recalls arriving at Stansted airport: “People were welcoming to us – and we thought, ‘well, we’ve come to the right place.’ We thought ‘we’ve got a new life,’ he said.

Like many refugees, Nathwani believes that those given sanctuary to Britain should pay it forward. So, he told his own story of personal gratitude to Britain, and of the Ugandan Asian contribution to our country, alongside refugees from each of the last seven decades at an event last summer marking the 70th anniversary of Britain signing the UN Refugee Convention.

They shared a belief that the British tradition of protecting refugees is something we could all take pride in, as long as we renew it when asked to act again today.

Now terrible scenes from Ukraine remind us why refugee protection matters. Russian tanks on the streets of another capital city. Parents saying goodbye to children at train stations.

These images evoke the Second World War that led to the Refugee Convention, and the need for it when Russia sent tanks into Hungary in 1956 and Prague in the 1960s.

Ukraine is different to Uganda. The British passports of the Ugandan Asians placed a special responsibility on Britain. That is perhaps a closer analogy to Hong Kong, where this government’s major new visa scheme to welcome Hong Kongers has been its biggest single migration policy decision post-Brexit.

Britain had some specific responsibilities too, when Kabul fell last summer, to those whose lives were in danger because they had worked with British forces.

On Ukraine, it will be more a question of Britain joining others by doing its bit. Ukraine’s neighbours will receive a much larger share of refugees. Over 350,000 people – predominantly women and children – crossed the border into Poland by the first weekend of the conflict, and to other neighbouring states such as Moldova, Romania and Hungary.

Most Ukranians pray for an end to this war, so that they can return home quickly. If the conflict is sustained, then it will be important to have a shared international resettlement programme.

Some worry that empathy for Ukranians may reflect a selective, racialised approach to refugee protection. The Bulgarian prime minister crudely stereotyped other refugees in committing to help Ukranians, saying: “These are not the refugees we have been used to. These are people who are European and so we welcome them”.

African and Indian students reported discriminatory behaviour at the Polish border. (Diplomatic intervention, secured a public commitment from the Polish government to admit those fleeing Ukraine, from every nationally or ethnicity).

Some western media commentators fall into similar traps. But this is not the case for British public attitudes as a whole. Initial snapshots of public opinion towards refugees from Ukraine – with 63 per cent of people supporting a bespoke refugee settlement programme, and 18 per cent opposed – are broadly in line with attitudes to refugees in general, and to specific crises, such as the broad wave of sympathy for Syrian refugees arising from the death of Alan Kurdi in 2015.

Because we know the story of (Vladimir) Putin, of the Taliban, and of (Bashar al-) Assad, the question ‘why are they fleeing?’ has been answered. It may be harder for those fleeing complex conflicts and abusive regimes that are not well-known, such as those in Eritrea or Yemen, to secure this benefit of the doubt.

What is needed is an asylum system that is orderly, effective and humane: which sees ‘the face behind the case’. Most people are balancers on immigration, so want to combine control and compassion, not have to choose between them.

The prime minister says Britain should be “out in front” in protecting refugees. Having allowed close family members of Ukrainians already here to come, he needs to decide how far Britain will match the more generous approach of Ireland and every EU country - offering Ukranians a three-year temporary visa.

The government has been surprised by the breadth of public, political and media support for refugees this week. There have been campaigns for refugees on the front pages of both the liberal Independent and the more conservative Daily Mail newspapers. The government is playing catch-up, but there is still time to get it right.

Sunder Katwala: Public opinion supports helping Ukrainian refugees