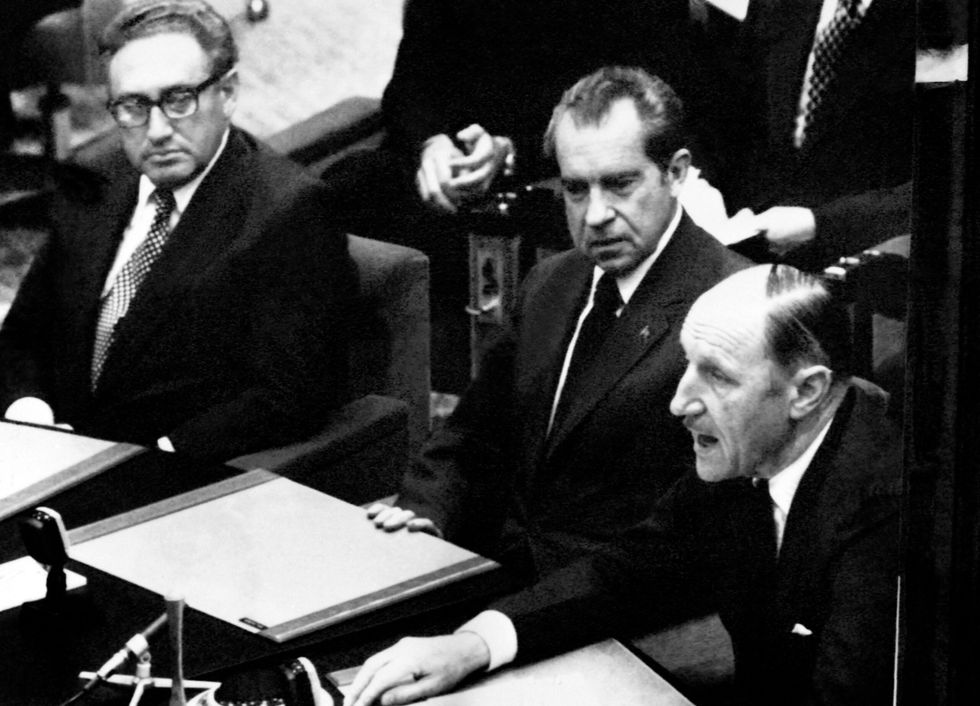

DR HENRY KISSINGER, who died last Wednesday (29), aged 100, was an American diplomat of Jewish-German extraction who served as national security adviser and secretary of state to US presidents Richard Nixon and his successor, Gerald Ford.

Kissinger’s long life was proof of the old adage, “You can fool all of the Americans all of the time.”

His obituary notices in many western newspapers, including British ones, have been mostly gushing, describing him as a great diplomat.

However, the reality is that he had a poor understanding of foreign affairs, not only in relation to India and Pakistan in the run up to the Bangladesh war of 1971, but also over his China policy.

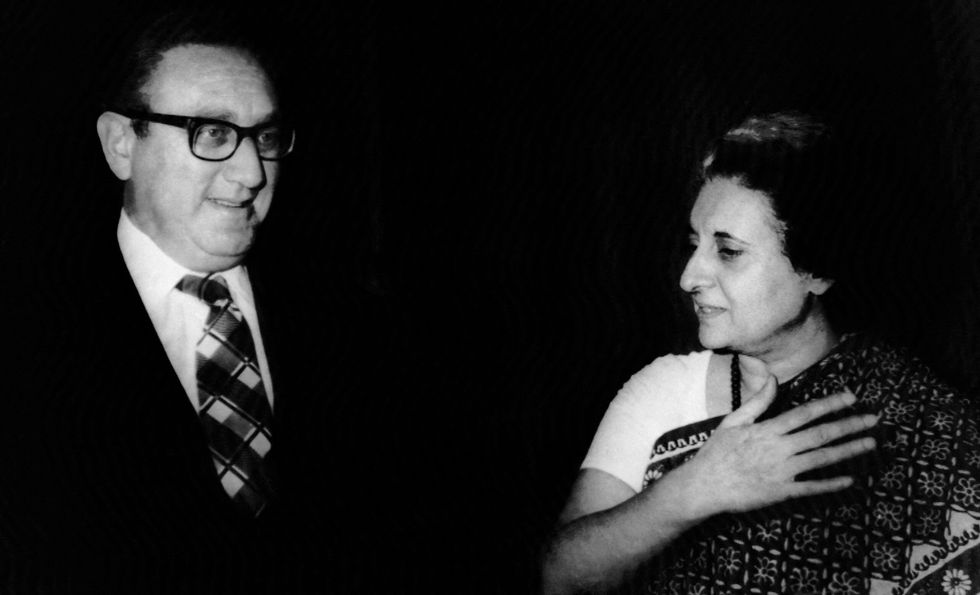

Kissinger tried to corner India and failed because he was outwitted by a more intuitive politician – Indira Gandhi. Much has been made of the fact that in recent years he apologised for his previous vulgar remarks about India and also tried to ingratiate himself with prime minister Narendra Modi’s government. But Kissinger was merely climbing aboard a bandwagon, having realised he had much earlier picked the losing side. He did much to damage US-India relations.

He always spoke with a distinctive German guttural accent.

“The Indians are bastards anyway,” was Kissinger’s profound take on Indians. “They are starting a war there,” he added, in a reference to an impending war between India and Pakistan.

He was rude about Indians; perhaps his conversational English – given his German origin – was a little limited – but he had no great love for the Pakistanis either. It could be he inherited the myth of Aryan superiority during his boyhood years in Germany.

Kissinger told Nixon at one point: “I tell you, the Pakistanis are fine people, but they are primitive in their mental structure. They just don’t have the subtlety of the Indians.”

His boss was accused of many things, but never of subtlety.

When Mrs Gandhi visited Washington in November 1971 with a view to getting American support to prevent the drift to war – and even before – Nixon was disturbed he did not find the Indian prime minister sexually desirable. “Undoubtedly the most unattractive women in the world are the Indian women,” said Nixon. “Undoubtedly,” he repeated.

He continued: “The most sexless, nothing, these people. I mean, people say, what about the Black Africans? Well, you can see something, the vitality there, I mean they have a little animal like charm, but god, those Indians, ack, pathetic. Uch.”

White House tapes show Nixon said: “To me, they turn me off. How the hell do they turn other people on, Henry? Tell me.”

Kissinger’s response is inaudible, but he did not discourage the president from his theme.

Nixon suggested to Kissinger that his own sexual neuroses were having an impact on foreign policy: “They turn me off. They are repulsive and it’s just easy to be tough with them.”

“While she was a bitch,” Kissinger said at one point, “we got what we wanted too. She will not be able to go home and say that the United States didn’t give her a warm reception and therefore in despair she’s got to go to war.”

“We really slobbered over the old witch,” said Nixon.

In a further conversation with his then secretary of state, William P Rogers, the president blurted out: “I don’t know how they reproduce!”

Kissinger was born Heinz Alfred Kissinger on May 27, 1923, in Fürth, Bavaria, Germany. He was the son of Louis Kissinger (1887–1982), a schoolteacher, and Paula (née Stern; 1901–1998), from Leutershausen.

On August 20, 1938, when Kissinger was 15 years old, he and his family fled Germany to avoid further Nazi persecution. The family briefly stopped in London before arriving in New York City on September 5.

Kissinger’s greatest failure has been in the field of China. He created the aura he was getting things done by undertaking secret trips. He made two to China in 1971 using aircraft supplied by Pakistan. Bringing China in from the cold was meant to represent the triumph of Kissinger’s foreign policy. But in this area, as in so many others, his thinking was deeply and fatally flawed.

Today, looking back, he would have recognised that the China policy, with which he is so closely associated, lies in tatters. What he did was help China to become a credible economic and military threat to the US. The damage that Kissinger has done is permanent.

Modern China is recognised as the west’s main adversary. Both the US and the UK, especially under the new foreign secretary, Lord David Cameron, are trying to undo the harm done by Kissinger and establish a pragmatic working relationship with China. In marked contrast, Cameron, as prime minister, wanted to use the British Indian community to build a special relationship with India.

There is no support for the Ukraine war among ordinary Indians, but Modi’s government has refused to break with Russia despite pressure from the west to do so. This dates back to 1971 when the Soviet Union proved a faithful ally of India. Again, the hidden hand of Kissinger can be detected behind India’s refusal to go against Russia, which has proved a tried and trusted ally since the days of the Bangladesh war.

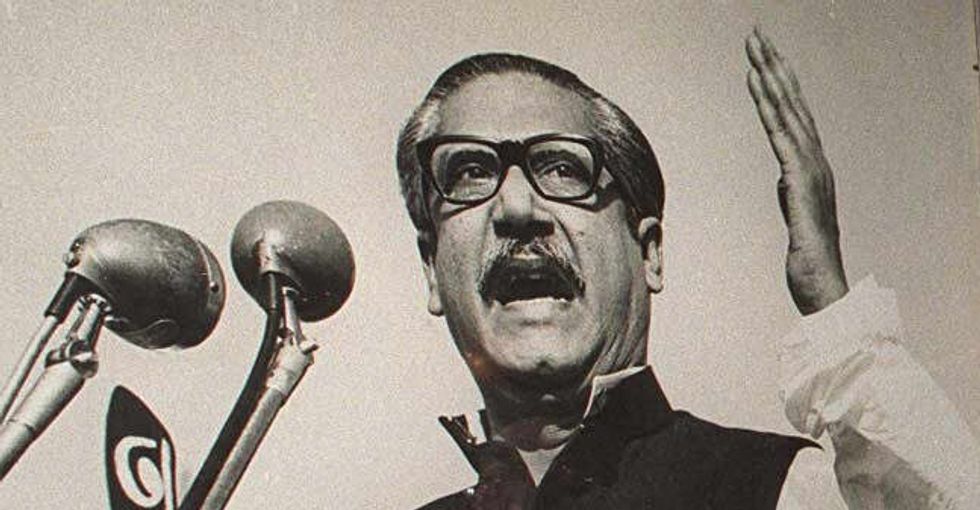

In 1971, Nixon and Kissinger backed Pakistan, although its army had conducted a campaign of genocide to stop East Pakistan breaking away and forming Bangladesh. Some 10 million refugees flowed into West Bengal from East Pakistan. The East Pakistani leader, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, who had won national elections and should have become prime minister of Pakistan, was arrested at his home in Dacca (now Dhaka) and spent the entire war in captivity in West Pakistan.

Zulfikar Ali Bhutto was as responsible for the break-up of Pakistan as the country’s military ruler, General Yahya Khan. Bhutto became leader of West Pakistan, but was hanged by another military leader, Gen Zia-ul Haq.

And Shiekh Mujib also met a violent end, when he was assassinated by a group of army officers in the new Bangladesh.

Like Nixon, Kissinger had no understanding of the politics of the subcontinent. That he came to be hailed as a great diplomat and thinker is probably the result of western group think.

A good case could be made for arguing Kissinger was guilty of encouraging or at least turning a blind eye to war crimes.

Mrs Gandhi’s democratic credentials were questioned after she imposed a state of emergency in India in 1975, but in 1971 she was on the right side of history.

The White House tapes have been analysed by, among others, Gary J Bass, a professor of politics and international affairs at Princeton University and the author of The Blood Telegram: Nixon, Kissinger and a Forgotten Genocide, which was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize.

His article in the New York Times on September 3, 2020, was headed: “The Terrible Cost of Presidential Racism. Recently declassified White House tapes reveal how President Nixon’s racism and misogyny led him to ignore the genocidal violence of the Pakistani military in what is today Bangladesh.”

His article was the definitive denunciation of Kissinger.

He began: “As Americans grapple with problems of racism and power, a newly declassified trove of White House tapes provides startling evidence of the bigotry voiced by President Richard M Nixon and Henry Kissinger, his national security adviser.

“The full content of these tapes reveal how US policy toward South Asia under Mr Nixon was influenced by his hatred of, and sexual repulsion toward, Indians. These new tapes are about one of the grimmest episodes of the Cold War, which brought ruin to Bangladesh in 1971. At that time, India tilted heavily toward the Soviet Union while a military dictatorship in Pakistan backed the United States. Pakistan flanked India on two sides: West Pakistan and the more populous, and mostly Bengali, East Pakistan.”

Bass explained: “In March 1971, after Bengali nationalists won a democratic election in Pakistan, the junta began a devastating crackdown on its own Bengali citizens. Mr Nixon and Mr Kissinger staunchly supported the military regime in Pakistan as it killed hundreds of thousands of Bengalis, with 10 million refugees fleeing into neighbouring India. New Delhi secretly trained and armed Bengali guerrillas. The crisis culminated in December 1971 when India defeated Pakistan in a short war that resulted in the creation of an independent Bangladesh.”

Bass said: “I documented the violent birth of Bangladesh and the disgraceful White House diplomacy around it in my book The Blood Telegram, published in 2013. Much of my evidence came from scores of White House tapes, which reveal Mr Nixon and Mr. Kissinger as they really operated behind closed doors. Yet many tapes still had long bleeps.

“In December 2012, I filed a legal request for a mandatory declassification review with the Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum. After considerable wrangling, the Nixon archivists at last released a few unbleeped tapes in May 2018 and July 2019, then 28 more in batches from October 2019 to this past May.”

He then recounted Nixon’s comments on Mrs Gandhi, adding, “It was stunning to hear a conversation between Mr Nixon, Mr Kissinger and HR Haldeman, the White House chief of staff, in the Oval Office in June 1971.”

Bass wrote: “Mr Kissinger has portrayed himself as above the racism of the Nixon White House, but the tapes show him joining in the bigotry, though the tapes cannot determine whether he truly shared the president’s prejudices or was just pandering to him.

“On June 3, 1971, Mr Kissinger was indignant at the Indians, while the country was sheltering millions of traumatised Bengali refugees who had fled the Pakistan army. He blamed the Indians for causing the refugee flow, apparently by their covert sponsorship of the Bengali insurgency. He then condemned Indians as a whole, his voice oozing with contempt, ‘They are a scavenging people.’

“On June 17, 1971 – in the same conversation as Mr Nixon’s outburst at ‘sexless’ Indian women – the president was furious at Kenneth B Keating, his ambassador to India, who two days earlier had confronted Mr Nixon and Mr Kissinger in the Oval Office, calling Pakistan’s crackdown ‘almost entirely a matter of genocide’.

“Mr Nixon now asked what ‘do the Indians have that takes even a Keating, for Christ, a 70-yearold’ – here there is cross-talk, but the word seems to be ‘bachelor’ or ‘bastard’. In reply, Mr Kissinger sweepingly explained, ‘They are superb flatterers, Mr President. They are masters at flattery. They are masters at subtle flattery. That’s how they survived 600 years. They suck up – their great skill is to suck up to people in key positions.’”

Bass concluded: “These emotional displays of prejudice help to explain a foreign policy debacle. Mr Nixon and Mr Kissinger’s policies toward South Asia in 1971 were not just a moral disaster, but a strategic fiasco on their own Cold War terms.

“While Mr Nixon and Mr Kissinger had some reasons to favour Pakistan, an American ally which was secretly helping to bring about their historic opening to China, their biases and emotions contributed to their excessive support for Pakistan’s murderous dictatorship throughout its atrocities.

“As Mr Kissinger’s own staff members had warned him, this one-sided approach handed India the opportunity to rip Pakistan in half, first by sponsoring the Bengali guerrillas and then with the war in December 1971 — resulting in a Cold War victory for the Soviet camp.

“For decades, Mr Nixon and Mr Kissinger have portrayed themselves as brilliant practitioners of realpolitik, running a foreign policy that dispassionately served the interests of the United States. But these declassified White House tapes confirm a starkly different picture: racism and misogyny at the highest levels, covered up for decades under ludicrous claims of national security.”

On a visit to India in 2005, Kissinger, then 82, made excuses: “[The foul language has] to be seen in the context of a cold war atmosphere 35 years ago, when I had paid a secret visit to China when President Nixon had not yet been there and India had made a kind of an alliance with the Soviet Union.”

“I regret that these words were used. I have extremely high regard for Mrs Gandhi as a statesman. The fact that we were at cross purposes at that time was inherent in the situation, but she was a great leader who did great things for her country.”

Less easy to gloss over was the fact that Nixon and Kissinger urged China to attack India by manufacturing a border incident during the Bangladesh war. China declined.

Kissinger and Le Duc Tho, a North Vietnamese diplomat and politician, were jointly offered the 1973 Nobel Peace Prize for their work on the Paris Peace Accords which prompted the withdrawal of American forces from the Vietnam war. Tho declined to accept the award on the grounds that peace had not actually been achieved in Vietnam. Kissinger donated his prize money to charity, did not attend the award ceremony and later offered to return his prize medal after the fall of South Vietnam to North Vietnamese forces 18 months later.

The Calcutta Club

The Calcutta Club The Bengal Club lawns

The Bengal Club lawns

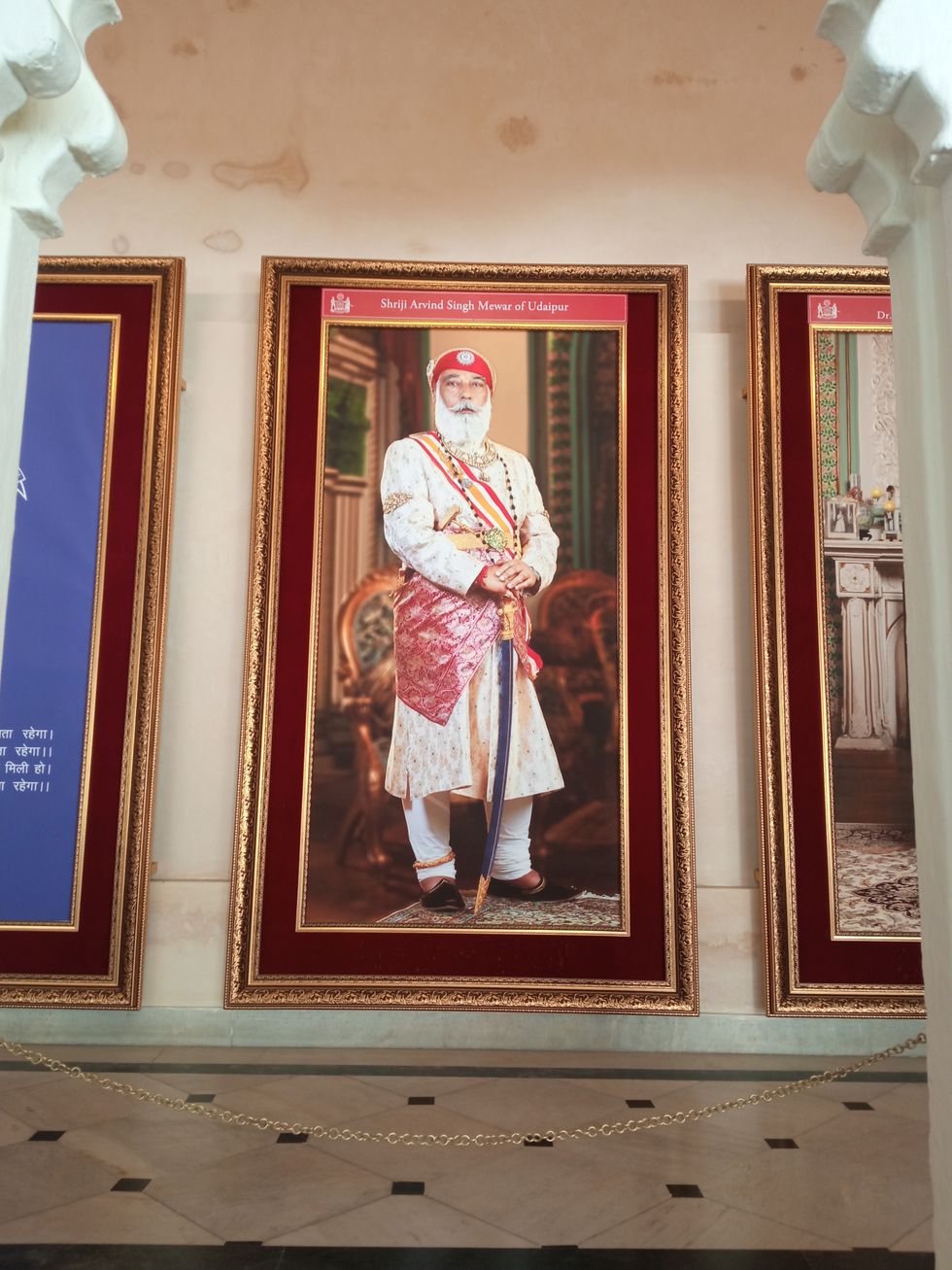

His portrait in the City Palace

His portrait in the City Palace

Pakistani artist Moazzam Ali Khan caught the attention of Bollywood legend Javed Akhtar with his soulful YouTube cover of Yeh Nain Deray Deray

Pakistani artist Moazzam Ali Khan caught the attention of Bollywood legend Javed Akhtar with his soulful YouTube cover of Yeh Nain Deray Deray John Abraham to headline action thriller Tehran

Getty Images for DIFF

John Abraham to headline action thriller Tehran

Getty Images for DIFF

Tikri Border, Haryana-Delhi by Aban Raza

Tikri Border, Haryana-Delhi by Aban Raza Harmz Matharu

Harmz Matharu Abhishek Bachchan in Be Happy

Abhishek Bachchan in Be Happy Devika's soulful vocals shine in her new Punjabi ballad Wisteria

Devika's soulful vocals shine in her new Punjabi ballad Wisteria Indian Idol star Nitin Kumar promises a soulful mix of qawwali, Sufi, and folk music at his upcoming UK performance

Indian Idol star Nitin Kumar promises a soulful mix of qawwali, Sufi, and folk music at his upcoming UK performance Kunal Kamra during his show

Wikipedia

Kunal Kamra during his show

Wikipedia

Swiss-Indian singer BombayMami is making waves with her bold style and sound

Swiss-Indian singer BombayMami is making waves with her bold style and sound Hania Aamir receives a questionable honour in London

Hania Aamir receives a questionable honour in London

A resident in Odessa, Ukraine, as smoke rises from a fire following a strike earlier this month amid the Russian invasion

A resident in Odessa, Ukraine, as smoke rises from a fire following a strike earlier this month amid the Russian invasion