By Rithika Siddhartha

INDIA’S coronavirus caseload topped 20 million on Tuesday (4) with some cities expected to reach the peak of the second wave in the next few days.

More than 350,000 new cases were reported in India on Tuesday, a fall from the high of 402,000 last week as the country’s creaking healthcare infrastructure struggled to cope with the huge number of cases, with shortages of medicines, hospital beds and medical oxygen.

Deaths on Tuesday rose 3,449 to 222,408, but many experts suspect the actual number to be much higher.

The relentless surge also finally forced the suspension of the Indian Premier League (IPL), involving some of cricket’s biggest global stars.

“If daily cases and deaths are analysed, there is a very early signal of movement in a positive direction,” senior health ministry official Lav Aggarwal told reporters. “But these are very early signals. There is a need to further analyse it.”

Eastern Eye spoke to frontline doctors across the country, some of who said the peak was a week to 10 days away.

India added around eight million new cases since the end of March in a ferocious wave blamed on virus variants and the government allowing most activities to resume as well as huge religious and political gatherings.

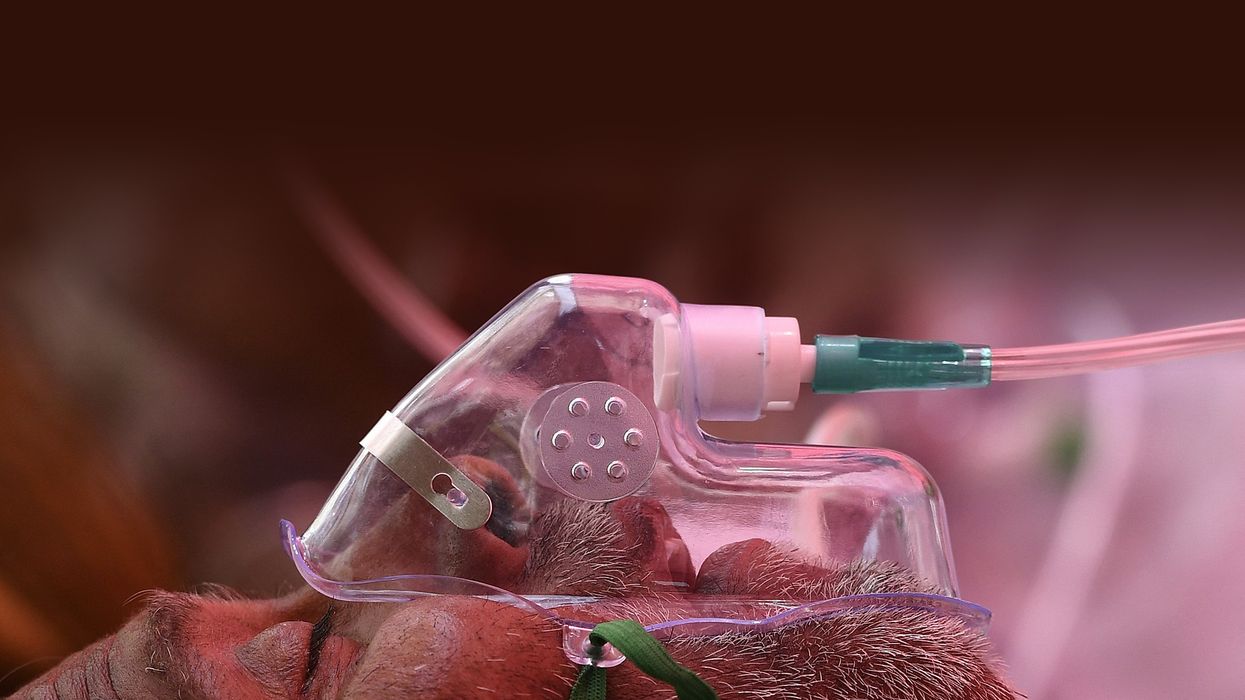

Dr Yogiraj Ray, of the Infectious Diseases and Beliaghata General Hospital (ID & BG) Hospital in Kolkata, said the number of patients who need oxygen, and the support of medical devices has surged in recent weeks. The hospital increased the number of beds in the intensive care unit (ICU) from 18 to 32, to cater to Covid patients.

“Almost all of them are on bi-pap or nasal canula or a ventilator,” Dr Ray said. “Or if they are off that support, chances are they may again need them.

“But the situation is so demanding that we have to place these devices in the general wards as well now,” he said, acknowledging that in such wards, it was not possible to maintain the stringent monitoring as happens in the ICU.

“Young and sick patients are increasing. The majority of patients are old people, the percentage of young people requiring devices is going up,” Dr Ray said.

West Bengal was one of five states in India that held regional (state assembly) elections in staggered phases during the months of March and April. Led by prime minister Narendra Modi, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) sought to topple the ruling Trinamool Congress, whose leader is chief minister Mamata Banerjee.

Modi and home minister Amit Shah campaigned heavily in the state, where elections started on March 27 and finished on April 29. At election rallies, attended by thousands of supporters, there was no social distancing and not everyone wore masks.

Dr Ray said although there was clear messaging about how to stay safe, the elections as well as lack of enforcement by authorities played a part in soaring infection rates.

“People used to complain about being in lockdown, now they can see what happens when they don’t wear masks,” he said.

Doctors and other healthcare staff like him have been working round the clock, treating the very sick, with few or no breaks. A typical day starts at 10 am and even after he is back home late in the evening, he said his mobile phone had become “like a call centre” with him offering support and guidance to patients those who needed it.

“I’m very stressed and have become irritable,” he revealed.

Across the country, in Gujarat, Dr Rajesh Chandra Mishra is an honorary consultant in intensive care at EPIC Hospital and Kidney Healthcare in Ahmedabad. He said where he previously saw a dozen patients in intensive care and in wards, that figure has now jumped to three digits.

The workload is now five to 10 times higher than it was, Dr Mishra said.

“Younger people are dying very fast. They come in late, with low oxygen, they are not probably able to recognise hypoxia early. And by the time they reach the hospital, they’re so severely hypoxic, that even if you intubate, put them on a ventilator, nothing works. Many times, their lungs rupture, their blood pressure is down, their kidneys fail.”

With the rise in cases, Dr Mishra started a helpline and a home care service to help and monitor those who display mild and moderate symptoms of the disease.

“Since we started our homecare service, we have treated around 1,500 patients with just Dolo (Paracetamol), rest and proper liquids. Only six out of 1,500 patients needed injections at home.”

He predicted that the peak in the state was about a week or 10 days away. In the past three weeks, he himself has been getting by on three hours of sleep, starting his day at 6am and going to bed at 3am.

Dr Mishra believes Covid will be around for a few years yet, although not at the scale currently seen in parts of the world – rather it will become endemic and sporadic, he said.

India’s pandemic has grown ever more dystopian, with crematoriums running out of space and patients, including a former ambassador, dying in hospital parking lots. Many have become volunteers, using technology and initiative to help those in dire need.

Rickshaw driver Mohammad Javed Khan in the central city of Bhopal turned his vehicle into a makeshift ambulance after he saw people carrying patients to hospitals on their backs as they were too poor to afford one.

“Even when (people) call ambulances, the ambulances are charging `5,000-`10,000 (£49-£98),” said Khan, who sold his wife’s jewellery to equip the rickshaw with medical equipment.

In the slums of Mumbai, Shanawaz Shaikh has provided free oxygen to thousands of people. Known popularly as the “oxygen man”, the 32-year-old sold his cherished SUV last June to fund the initiative after his friend’s pregnant cousin died in a rickshaw while trying to get admitted to a hospital.

“She died because she couldn’t get oxygen in time,” he said.

He never expected to be fielding so many requests nearly a year later. “We used to get around 40 calls a day last year, now it’s more like 500,” he said.

Shaikh’s team of 20 volunteers are also battling a massive shortage, made worse by profiteers.

“It’s a test of one’s faith,” he said, describing how he sometimes travels dozens of kilometres to source oxygen for desperate patients.

The city has not witnessed the kind of scenes seen elsewhere in India, which have been making headlines recently.

Dr Lancelot Pinto, a consultant respirologist at Mumbai’s PD Hinduja Hospital, told Eastern Eye on Monday (3), “There’s a war room which triages reasonably well in the city, so you don’t get a bed unless you really need one. Most of the individuals in our beds this time who were on oxygen really needed to be in the hospital. So, we didn’t have a lot of individuals who were there just because they were anxious and pulled the right strings.”

Across India, however, it often did not matter how important the patient was.

Ashok Amrohi, the country’s former ambassador to Brunei, Mozambique and Algeria, died in the early hours of last Wednesday (28) after waiting for a bed in the parking lot of Gurgaon’s Medanta hospital for nearly five hours, media reports said.

His wife, Yamini Amrohi, said her husband had been ill for the past week, so they went to the healthcare facility in Gurgaon, outside Delhi.

“We first waited first for one and-a-half hours. He was sitting in the front seat of the car.”

The family was told they needed a Covid test. However, the process to get the former diplomat the test “stretched on indeterminately”, reports said.

His wife was quoted as saying, “I went to the place at least three times begging them for someone to look at him… I was crying, I was shouting that unke saanse tham rahi hai (his breath is stopping). But nobody helped.

“Sometime after midnight, he died from a cardiac arrest. He passed away sitting in the car. I went to the hospital and told them, ‘all of you are murderers.’”

Similar scenes of distraught family members seeking help for their loved ones have been seen outside hospitals in Delhi and other cities.

As infection rates escalate, some states have imposed lockdowns, including Bihar, a state of around 120 million people, which on Tuesday became the latest Indian region to impose restrictions, and Maharashtra, whose capital is Mumbai.

Last Wednesday (28), the state’s health minister Rajesh Tope said Maharashtra’s lockdown may be extended by a fortnight until mid-May to try to halt a rise in cases. The state will also not go through with a plan to open vaccinations to everyone aged over 18 from last Saturday (1) due to a shortage of doses.

“This time around in terms of infections, I think a good 80 per cent of infections seem to happen in apartments and high rises. It’s not so much in the slums this time around,” Dr Pinto told Eastern Eye.

He also noted that the infections seem to be a lot stronger this time.

“We’re observing a lot more individuals having prolonged fevers. The first time around, it would be two or three days of fever and individuals would settle. But this time, the fever is lasting for eight, nine or 10 days, just refusing to budge. It is something that we’re seeing a lot this time around and it is making us all nervous. When somebody has fever, which goes on to the eighth or ninth day, you are constantly on the edge wondering whether their oxygen levels are going to drop sometime soon.”

In the second wave, some doctors are also seeing young children infected by Covid and needing medical attention with upper respiratory problems, or post Covid with multi-organ failure, according to Dr Ajit Sowani, head of the Neurosciences department at Zydus Hospital in Ahmedabad. It has bucked the national trend of lack of oxygen as the facility had a private plant built at the time the hospital was set up. And its promoter is Zydus Cadilla, which makes the drug remdesivir.

Dr Sowani told Eastern Eye he sees a lot of patients virtually, so they do not need to come to hospital. He predicted a decline in cases by the middle of May.

One report said the Indian government modelling points to a peak by Wednesday (5), a few days earlier than thought.

“The only way to stop the spread of corona now is a full lockdown ... GOI’s inaction is killing many innocent people,” opposition Congress leader Rahul Gandhi said on Twitter, referring to the central government.

However, according to Dr Pinto, “Unfortunately, mortality and severe disease tends to lag behind the peak of infections by a couple of weeks. There’s usually a two-or three-week lag between the peak of infections and the peak of deaths.

“We’re possibly one week into those two-three weeks that I’m alluding to, but in the next couple of weeks, we still are likely to be stretched in terms of critical-care bed needs, in terms of high-dependency unit needs.”

Court ‘last hope’ for oxygen supplies

Supplies of medical oxygen have hit hospitals hard, with many resorting to appeals on social media for help.

A court in New Delhi has become the last hope for many hospitals struggling to get oxygen for patients as supplies run low while state and central government officials bicker over who is responsible.

A two-judge bench of the Delhi high court has been holding almost daily video conferences to hear petitions from hospitals invoking India’s constitutional right to protection of life, with local and federal officials attending.

Last Sunday (2), with just 30 minutes of oxygen left for 42 patients at Sitaram Bhartia hospital, and new supplies nowhere in sight, the hospital approached the court as a “last resort” for help, lawyer Shyel Trehan said. The judges ordered the Delhi state government to arrange supplies.

“Oxygen cylinders arrived soon after the hearing, and a tank arrived a few hours later,” Trehan said.

The shortage of medical oxygen has plagued the city of 20 million people, with unprecedented scenes of patients dying on hospital beds, in ambulances and in carparks, gasping for air.

Delhi is recording about 20,000 new Covid-19 cases a day. As the health system buckles, the city says it needs 976 tonnes of medical oxygen daily, but gets fewer than 490 tonnes, given by the federal government.

Representatives of the ruling central BJP-led government, which is managing supplies nationally, have told the court they were doing all that was possible. They blamed the Delhi government, run by a rival party, for politicising the issue.

Last weekend, when Delhi state representatives again flagged concerns that oxygen supplies were not arriving in time, one of the judges, justice Vipin Sanghi, lashed out, saying “water has gone over the head. Enough is enough...”

In April, Sanghi told government officials they should “beg, borrow, steal or import” oxygen supplies to meet the city’s needs.

In many cases, volunteer groups have come to the rescue. Outside a temple in the capital, Sikh volunteers have been providing oxygen to patients lying on benches inside makeshift tents, hooked up to a giant cylinder. Every 20 minutes or so, a new patient came in.

“No one should die because of a lack of oxygen. It’s a small thing otherwise, but now, it is the one thing every one needs,” said Gurpreet Singh Rummy, who runs the service.

‘Better vaccine messaging needed’As infection cases rise, the country is struggling to keep up with demands for vaccination.

Two months ago, the health minister said India was in the “end game” of the pandemic as it sent millions of vaccines abroad, but now exports have stopped and people are desperate to be inoculated.

Until now, only “frontline” workers like medical staff, people over 45 and those with pre-existing illnesses have got the Oxford-AstraZeneca (known as Covishield) or Covaxin shots.

So far, around 150 million shots have been administered, which is 11.5 per cent of the population of 1.3 billion. Just 25 million have had two doses.

All adults, around 600 million, are now eligible to get vaccinated, but many states said they have insufficient stocks.

“Half my family is positive, so everybody wanted to get vaccinated,” data scientist Megha Srivastava, 35, said in Delhi. “It won’t completely protect us, but it will ensure that even if we get infected, we’ll recover.”

Dr Lancelot Pinto, a consultant respirologist at Mumbai’s PD Hinduja Hospital, acknowledged that “vaccine shortages are a real problem right now”.

He told Eastern Eye that some people who took the first dose of the Oxford AstraZeneca vaccine are struggling to get their second dose.

There also could have been better communication about vaccines saving lives, he added.

“We needed to be proactive, telling people that if you hear stories of individuals getting infected after receiving two doses of the vaccine, it’s not shocking at all, it’s expected.

“The question should be, how many of them had severe disease, how many of them ended up in a hospital? How many of them passed away because of the disease? And that number is a really small fraction. But unfortunately, this was not out there.

“People on social media started saying, ‘My friend had two doses and got the disease… so why are we taking the vaccine to begin with?’ I think that’s where communication plays a very important role.

“We have a whole database of healthcare workers now, who received two doses of the vaccine. All the government needs to do is release that database saying, during the current surge, how many of them actually got infected? What proportion of them ended up in an ICU? What proportion of them died? And data like that being out there in the public domain can raise much more confidence (in vaccines).”

(With Agencies)