NARENDRA MODI was sworn in as prime minister of India last Sunday (9) for the third time, but newspapers around the world have all been asking the same set of searching questions.

Why did the exit polls get it so wrong in predicting a “super majority” of anything up to 400 in the 543-seat Lok Sabha (lower house of parliament), when the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) could only manage 240 – well short of the 273 needed to form a government?

With his allies, the NDA (National Democratic Alliance) got up to 293 MPs, so Modi was chosen prime minister once again, but this time at the head of a coalition government.

Is Modi capable of making the compromises necessary to keep his allies on board? The opposition INDIA bloc got 237 seats – just three short of the BJP tally.

Congress, headed by Rahul Gandhi, got 99 seats, up from 52 in 2019. Will the 28 parties that comprise INDIA hold together in coming months and years? Or can some opposition MPs be persuaded to defect to the NDA?

One of the most negative assessments of Modi came from Kapil Komireddi, author of Malevolent Republic: A Short History of the New India. In a piece for the Sunday Times, he declared: “This is the beginning of the end.”

He said: “On Tuesday (4), Narendra Modi awoke as the father of what his followers call New India – a Hindu-first state built on the remains of the secular ideals that had been the basis of India’s national identity for more than six decades. By the time he retired to bed, New India was dead and his aura of invincibility was in shreds.”

He pointed out: “In Uttar Pradesh, the populous Hindu-nationalist stronghold and the most consequential state by numbers, Modi’s BJP went from 62 seats to 35. The BJP was defeated even in Ayodhya, where, in January, Modi had inaugurated a Hindu temple on the site of a razed Mughal-era mosque, and held it up as the emblem of his New India.

“The message was unmistakable. Even televangelists who had spent the decade cheering Modi on saw in the outcome a repudiation of his sectarian ideology.”

The author commented: “The surprising thing is not that Modi did not win a majority. It is that he has not become extinct.”

Komireddi was equally scathing about Rahul Gandhi: “If Modi continues in office, the credit has to go to the opposition, principally Congress – the Indian National Congress Party.

“Its argument that the deck was stacked against it by Modi, who seized control of virtually every autonomous institution and set them on the opposition, obscures the fact that none of this is novel.

“In 1975, Indira Gandhi went further than Modi when she shelved the constitution and ruled for 21 months as a dictator.

Habeas corpus was suspended, the press was censored, and the opposition thrown in jail.

“When elections were called in 1977, the opposition set aside their differences and united against the government. Gandhi did not merely lose the election: she lost her own seat.

“In 2024, many of the opposition parties pretending to be martyrs for democracy in Modi’s India are in reality profoundly antidemocratic entities run for the benefit of the families that own them. The most egregious of them all is Congress, which pioneered dynasticism.

“Since 1977, barring a brief interregnum in the 1990s, the party, operating in the most populous democracy on earth, has not known a single leader outside one family. In no other serious democracy would Rahul Gandhi, the sixth-generation scion of the Nehru-Gandhi clan, survive after losing three successive general elections. But In India, he is being exalted by sycophants for inflicting a ‘moral’ defeat on Modi.”

He said: “Last week, Modi was the most powerful Indian leader in decades. Now he is trapped in an intractable position that he is not equipped by temperament to endure and from which he cannot easily extricate himself. No one should underestimate Modi’s Napoleonic flair for staging comebacks. But after ten years of wielding untrammelled power, he now looks cornered.”

Congress general secretary Jairam Ramesh was scornful of the notion that Modi had matched Jawaharlal Nehru: “It is being propagated that Mr Narendra Modi is the first to receive a mandate thrice in a row after Jawaharlal Nehru.

“How leading a party to 240 seats is a mandate is not explained. Nehru, on the other hand, got 364 seats in 1952, 371 seats in 1957, and 361 seats in 1962 – a two-thirds majority each time. Yet he remained a complete democrat, nurturing parliament so very carefully with his constant presence.”

The BBC reported the findings of the exit polls: “Though the individual numbers vary, they predict that the NDA will get between 355 and 380 seats. The INDIA bloc is expected to get 125 to 165 seats, according to the Reuters news agency.

“On its own, the BJP may win about 327 seats, not quite meeting its 370-seat target. That confidence seemed justified when exit polls released on Saturday evening showed the BJP and its National Democratic Alliance partners heading for a resounding victory — even the 400-seat supermajority in the 543-seat parliament he was shooting for.”

Modi claimed victory with a message on X: “I can say with confidence that the people of India have voted in record numbers to re-elect the NDA government. The opportunistic India Alliance failed to strike a chord with the voters. They are casteist, communal, and corrupt.”

The Telegraph in India suggested that voters might not have been honest with pollsters. It wondered: “Are voters truthful when asked who they voted for? Should they be? In a country as diverse and socially layered as India, there are multiple reasons why people may prevaricate after voting. Fear of reprisal, unwillingness to mention a choice against the majority, distrust of questioners from a different social class, the right to silence or to deliberate misdirection on what is perceived as a purely private matter are some of these.

“All such exercises leave a margin for honest error, much of which can be corrected by addressing weaknesses through analysis. Urban bias, the underrepresentation of marginalised groups and of women, over-confident modelling of voter types may all be corrected.

“There is even less excuse when research agencies appear to favour the ruling party. That may be prejudice; it may also raise questions about funding. Further, the magnification of mistaken readings by the media casts a shadow on journalistic integrity.

“When much of the media are being perceived as mouthpieces of the ruling regime, exit polls giving it an overwhelming majority and media channels thumping tables with that information cause suspicions more of deliberate misdirection than incompetence. And turn independent media into a myth.”

The Times of London carried a leader on Modi’s performance: “It was a victory, but it felt like a defeat. The blame falls squarely on the shoulders of the party’s leader and the incumbent prime minister, Narendra Modi, who has dominated India’s political scene for a decade.”

It said: “Modi misjudged what voters wanted from government. In contrast to Congress, which has always sought to define India as a secular state, Modi’s platform has been to place Hindu nationalism at the centre of the country’s politics. The de-molition of a mosque important to Muslims and the rebuilding on its site of a vast temple to the Hindu god Ram has been the most powerful and contentious symbol of this intent. The country’s 172 million Muslims, 14 per cent of the population, have suffered increasing harassment. A crackdown on press freedom was also a misjudgement.”

But it added: “To be fair, Mr Modi has not focused solely on nationalism. He also promised to boost the economy, and has succeeded: India grew 7.2 per cent last year and 8.7 per cent the year before. In 2022 it overtook Britain to become the world’s fifth biggest economy. Having now overtaken China as the world’s most populous country, India is slated in some forecasts to become the world’s second biggest economy by 2050, surpassing the United States. Yet, India’s poor have not benefited nearly enough from the government’s policies and they have punished the BJP accordingly.

“There’s a lesson for him in the election result. Bullying Muslims and making the rich richer is not good enough. India’s poor want to see a material improvement to their lives. Modi now needs to deliver that.”

It also said: “It is to India’s credit that the poor are not, as they are in many countries, powerless. With 968 million people eligible to vote, its election was the biggest-ever exercise in democracy. The shock to Modi was dealt principally by the Dalits, the untouchables, who are regarded with such contempt that they are not even members of India’s caste system.

“Their votes, particularly in the BJP’s northern heartland, thwarted Modi. The frustrated masses have thus deprived the ruling party of the power it had come to regard as its by right, as in South Africa where a similar rebuke was issued to the ruling African National Congress.”

In 2014 and 2019, Modi’s personal majority in Varanasi was 371,784 (36.14 per cent) and 479,505 (45.2 per cent) respectively. This time it came down to 152,513 (31.72 per cent).

In the Financial Times, “The Big Read” was headed: “The humbling of Narendra Modi.” It said: “Indians are now trying to fathom what the paring back of Modi’s electoral support might mean in practice. Modi’s two biggest junior coalition partners, regional parties Telugu Desam Party and Janata Dal (United), which won 16 and 12 seats respectively, both have significant support from Muslim voters, and they could play a role in moderating some of the Indian leader’s Hindutva programmes.

“Indian businesses and foreign investors are racing to make sense of the new reality. Before this week’s poll upset, most had counted on Modi entering a third term with an agenda to pursue more market-friendly policies, including possible changes to land and labour laws.” Sanjeev Kumar, a BJP activist, told the paper: “I don’t think the government will be able to complete their full term.”

The BBC’s India commentator, Soutik Biswas, said Modi’s main allies, N Chandrababu Naidu and Nitish Kumar, who lead the Telugu Desam Party (TDP) and Janata Dal (United) respectively, were “veteran astute leaders”. Naidu had once referred to Modi as a “terrorist”. However, “politics makes for strange bedfellows – India is no stranger to that fact”.

In fact, Nitish Kumar, nine times chief minister of Bihar, has switched sides five times, earning the epithet, “Paltu Ram” (one who flip flops). He was a founding member of the INDIA bloc but joined the BJP before the election.

The New York Times, which analysed, “Where India Turned Against Modi”, said: “The BJP’s losses were sprinkled around the country, from Maharashtra in the west to West Bengal in the east.

“But Modi’s biggest setback came where it was least expected: the northern belt where his party was well entrenched and its Hindu-nationalist ideology had strong backing.

“In Uttar Pradesh, India’s largest state, with a population of 240 million, the BJP won just 33 seats, down from 62 in the previous election. It was in this northern state that Modi in January inaugurated the lavish Ram temple, seen as one of his biggest offerings to his Hindu support base.

But the BJP’s chest-thumping over its Hindu-first policies turned off many lower-caste voters more concerned with issues like unemployment, inflation and social justice.

“In the important state of Maharashtra, home to India’s business and entertainment capital, Mumbai, the BJP won only nine seats, down from 23 in the last election. The party’s coalition partners suffered even worse losses.

“The BJP did have some good news – it continued to expand its support in the south, where it has struggled to establish a lasting foothold. In Andhra Pradesh, it formed a strong local alliance with two secular parties, and their coalition won 21 of 25 seats because of the unpopularity of the party in power in the state. It won a seat for the first time in the left-dominated state of Kerala and several seats in the state of Telangana.

“The party’s most impressive gains came in the state of Odisha in the east. That state is part of the ‘tribal belt,’ which weaves across central India and is the only part of the country where the BJP has unified support. Its relatively poor communities have been skilfully targeted by the BJP’s Hindu-first politics and welfare benefits.

“But the party’s progress in eastern and southern India was far from enough to make up for its losses in the northern regions.

“Now, with Modi deprived of the landslide victory he had sought, the country will see how he responds. Some of the strains in India’s democracy might be mended as Modi is forced to consult with coalition partners who could restrain his more authoritarian tendencies. Or he could crack down more fiercely than ever, worried about losing more ground to a revived opposition.”

Now comes the task of forming a government. On Monday (10), the New York Times reported: “As a humbled Narendra Modi was sworn in on Sunday for a third term as India’s prime minister, the political air in New Delhi appeared transformed.

“The election that ended last week stripped Modi of his parliamentary majority and forced him to turn to a diverse set of coalition partners to stay in power. Now, these other parties are enjoying something that for years was singularly Modi’s: relevance and the spotlight. Their leaders have been swarmed by TV crews while on their way to present demands and policy opinions to Modi. His opponents, too, have been getting airtime, with stations cutting live to their news conferences, something unheard-of in recent years.

According to the FT, “Modi’s cabinet was also sworn in on last Sunday, with many from his last government returning. Those include his right-hand man, Amit Shah, a powerful operator who controlled many of India’s security agencies as home minister. Also in the line-up are Piyush Goyal, Nirmala Sitharaman, and Subrahmanyam Jaishankar.”

Bhool Chuk Maaf

Bhool Chuk Maaf If You Know You Know

If You Know You Know Asif Khan

Asif Khan Sanam figure out why. Teri Kasam

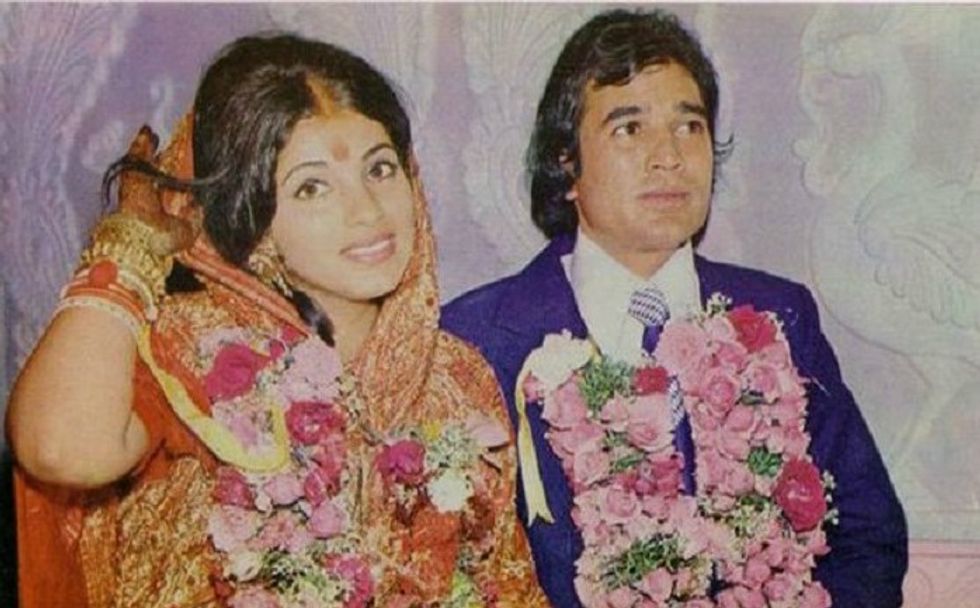

Sanam figure out why. Teri Kasam Dimple Kapadia and Rajesh Khanna on their wedding day

Dimple Kapadia and Rajesh Khanna on their wedding day Atif Aslam

Atif Aslam

Anoushka Shankar

Anoushka Shankar Nilesha Chauvet

Nilesha Chauvet

Pieter Elbers

Pieter Elbers