India’s growth rate will slow by up to half a percentage point due to the government’s decision to scrap high-value banknotes, the top finance ministry economist said on Tuesday, challenging independent estimates of a far bigger impact.

Chief economic adviser Arvind Subramanian rejected the view of the International Monetary Fund, where he used to work, that growth would be knocked a full percentage point lower by prime minister Narendra Modi’s shock decision in November to scrap 86 percent of the cash in circulation.

Modi launched the “demonetisation” drive to expose untaxed wealth and the proceeds of crime and corruption. Yet the measure - unprecedented in a stable, modern, peacetime democracy - has caused huge disruption to daily and business life in Asia’s third-largest economy.

It will also complicate the fiscal arithmetic in finance minister Arun Jaitley’s fourth annual budget, which he will present to parliament on Wednesday.

Presenting India’s pre-budget Economic Survey, which combines analysis and forecasts with a broader look at policy issues, Subramanian called demonetisation a “radical currency-cum-governance-cum social-engineering measure”.

He also maintained the currency squeeze was “less severe than is commonly perceived”.

‘SIGNIFICANT HARDSHIPS’

Still, Subramanian acknowledged that official GDP figures may not fully reflect the “real and significant hardships” experienced by the informal sector, in which an estimated nine out of 10 Indian workers are employed.

Without giving a figure for growth in the fiscal year that ends in March, Subramanian said it was likely to be between one- quarter and one-half percentage point below an earlier official forecast of around 7 percent.

Growth is expected to “return to normal” in 2017/18, when it is forecast in a 6.75-7.5 percent range, as cash liquidity is restored to the economy, according to the 335-page report.

By contrast, the IMF slashed its India growth forecast for the current fiscal year by a full point to 6.6 percent, handing the title of the world’s fastest-growing economy back to China, which reported 6.7 percent growth for 2016.

Subramanian pointedly declined to comment on whether there had been failings in the planning and implementation of the banknote ban. He expected that a shortage of new 500 rupee ($7.40) and 2,000 rupee notes to end by April.

The new notes are being issued to replace high-value ones scrapped overnight on Nov. 8.

NO LONGER IN DENIAL

Despite Subramanian’s cautious assessment, private sector economists said it was important he at least recognised that demonetisation had taken a toll on the Indian economy.

“This is perhaps the first acknowledgement coming from the government. Otherwise so far there has been a denial,” said Aneesh Srivastava, chief investment office at IDBI Federal Life Insurance Co in Mumbai.

Jaitley is expected in Wednesday’s budget to offer some tax “sops” to individuals to ease the pain of demonetisation, and ramp up public sector investment to offset weak consumption and private capital investment.

Such steps would seek to boost the electoral prospects of Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party in a round of five regional elections that kick off this weekend, the most important in the battleground state of Uttar Pradesh.

The survey said government pay rises and muted tax receipts could put pressure on the fiscal deficit in the coming fiscal year. A sharp rise in prices could also cap the headroom to ease monetary policy, it added.

Senior officials say Jaitley may allow the federal deficit to overshoot an earlier target of 3 percent of GDP to create room for more public investment - a move against that ratings agencies such as Standard & Poor’s have warned against because of India’s high national debt.

Subramanian took a poke at the “poor standards” of the ratings agencies and included a factbox in his report that chided S&P for upgrading China despite its slowing growth and deteriorating debt metrics, while overlooking India.

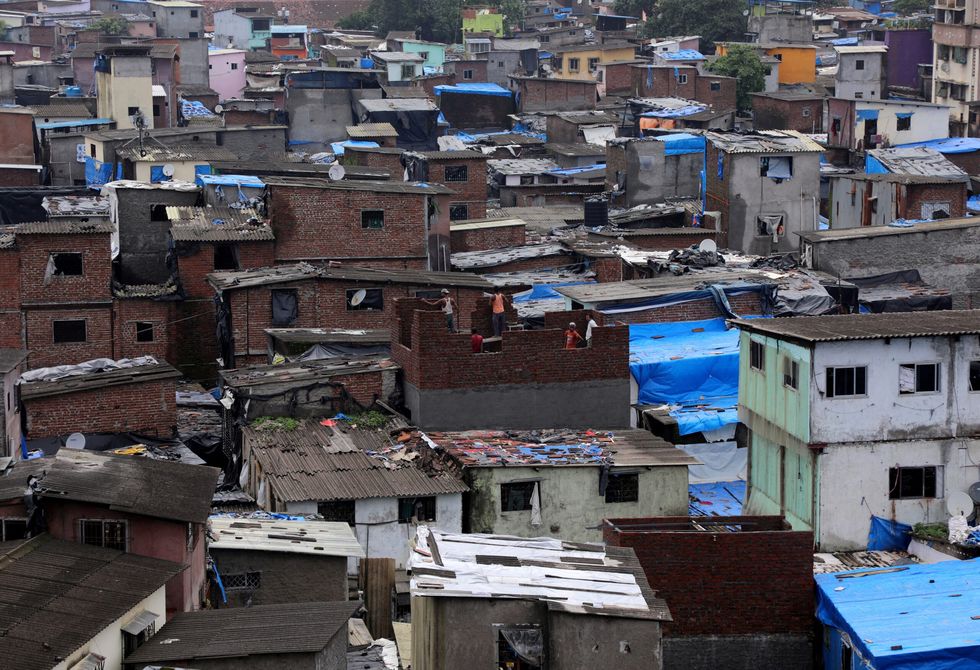

Dharavi slum in Mumbai

Dharavi slum in Mumbai