A proposed Indian law on the collection and use of genetic data to tackle crime can violate privacy, and target minorities and marginalised communities disproportionately, according to technology experts and human rights groups.

The DNA Technology Regulation Bill allows the profiling of victims, those accused of crimes, and those reported missing, and storing of their DNA information in national and regional data banks. It also aims to set up a DNA Regulatory Board.

The bill was tabled in parliament in February and is expected to be passed in the current session that runs until August 31.

Privacy advocates say the data can be misused for caste-based or community profiling in a country where minority groups are disproportionately criminalised, and that privacy violations are also likely as there is no law to protect personal data.

"The bill creates an umbrella databank for multiple purposes; the main concern is the lack of clarity on what data may be stored," said Shambhavi Naik, a research fellow at Takshashila Institution's technology and policy programme.

"There are privacy concerns because DNA discloses information about one's relatives and ancestors, as well," she added.

There are some 40,000 unidentified bodies and more than 60,000 children reported missing in India every year, according to official data.

The use of DNA technology, while not infallible, will minimise errors in criminal investigations and "improve the justice delivery system," said Jairam Ramesh, head of the parliamentary committee that examined the bill.

The bill provides for safeguards "to ensure privacy is not violated wantonly and egregiously. More safeguards should certainly be considered as we gain further experience with the use of technology," said Ramesh, a member of the opposition.

A spokesperson for the information technology ministry did not respond to a request for comment.

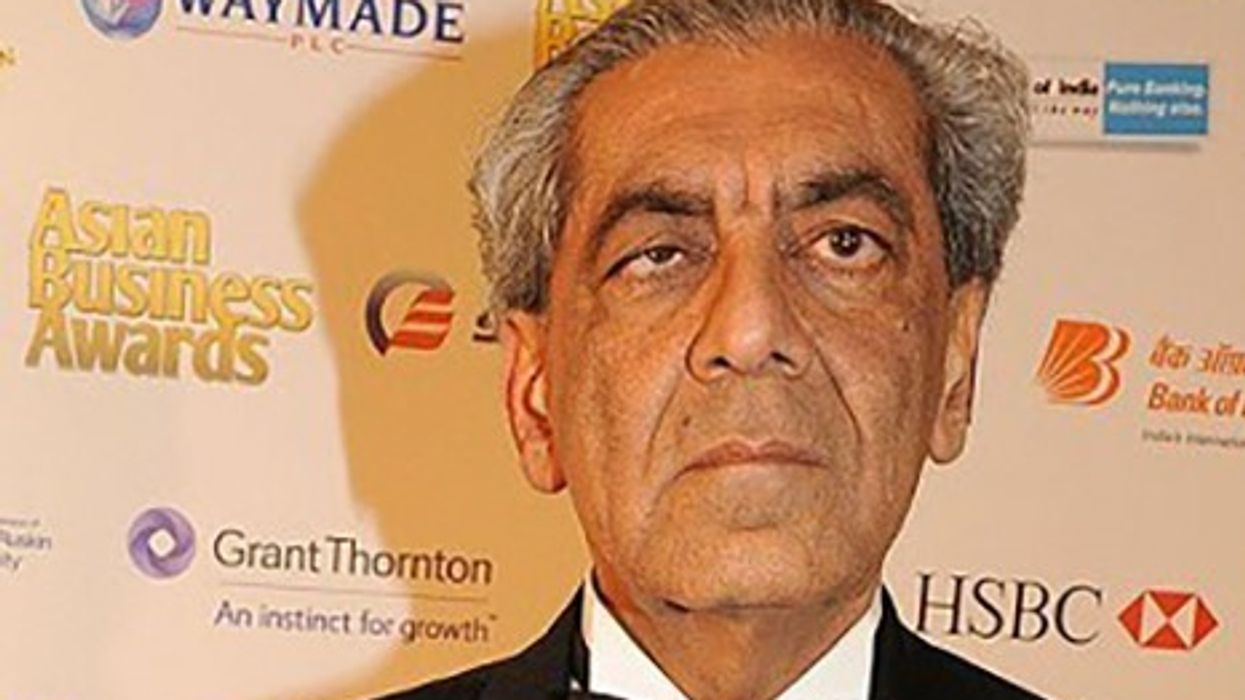

DNA can reveal sensitive information that can be used to criminalise a community or caste, said Asaduddin Owaisi, a member of parliament, noting that a majority of those arrested belong to the Dalit, Muslim or indigenous Adivasi communities.

"When the data being collected is as sensitive as DNA, it requires additional protections," he said in a note of dissent against the proposed bill, as "the potential for misuse is high, and the possible harm is so significant."

"In the absence of a statutory framework protecting the right to privacy, this bill will cause irreversible damage to individuals' right to privacy, as well as the criminal justice system," he added.

With an aim to modernise India's police force and its information gathering and criminal identification processes, authorities are installing facial recognition systems in airports, railways stations and polling booths in the country.

If the DNA data bank is linked to other surveillance systems like facial recognition "without accountability or oversight, that's a big problem," said Raman Jit Singh Chima, Asia policy counsel at Access Now, a digital rights group.

"A DNA database can be useful, but it needs a regulatory backstop that India does not have. The DNA Tech bill should not come before the personal data protection bill," he said.