NOW that it has been announced that the Indian general election will be held between April 19 and June 1, many books and articles both for and against Narendra Modi will be written about the country’s prime minister.

Firmly in the latter category is Christophe Jaffrelot’s Gujarat Under Modi: Laboratory of Today’s India, which was launched recently at the South Asia Centre at the London School of Economics (LSE).

Modi was three times elected chief minister of Gujarat and voted in as prime minister twice, in 2014 and 2019 – and a possible hattrick in 2024.

Jaffrelot’s thesis is that Gujarat has acted as a political laboratory for Modi, in that the strategy he used allegedly to subvert the rule of law in his native state has been applied at the centre in Delhi.

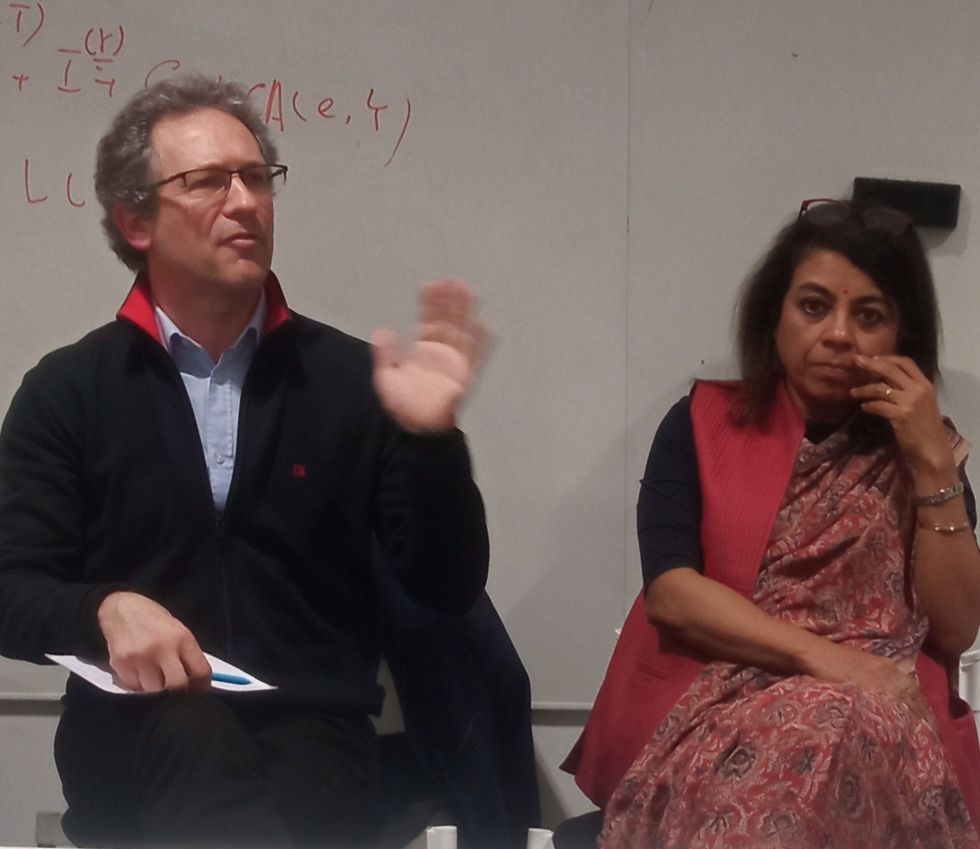

The French academic, a long-time Modi critic, is the Avantha chair and professor of Indian politics and sociology at the India Institute at King’s College London.

At the book launch, he was introduced by Mukulika Banerjee, who is associate professor in the department of anthropology at the LSE and a former director of its South Asia Centre.

“Clearly, this is a book that’s much anticipated,” she said. “People here are familiar with Christophe’s work, and he’s unafraid in articulating them, which is becoming a raity in the landscape of Indian politics.”

In his book, Jaffrelot sets out his main arguments against Modi, who is likely to be the main issue in the general election.

The prime minister’s supporters – many of them in the UK – will insist India has become a dynamic economic power precisely because of his leadership.

But Jaffrelot said: “This book deals with a unique political object: the transformation of Gujarat into what I called, in 2001, ‘a laboratory for Hindu nationalism’ and what (the late American historian) Howard Spodek in 2010 called ‘the Hindutva laboratory’ after the rise to power of Narendra Modi, who governed the state for a record number of years – between 2001 and 2014.

“While Spodek and I published our work in which these quotations appeared before Modi became prime minister, we are today in a position to identify elements of continuity between the political model he invented in Gujarat and the way he transposed them to the national level.”

The book also refers to the making of a “deeper state” and says: “The main actors here are the activists of the Sangh Parivar, including the militants of vigilante groups like the Bajrang Dal, which are policing society at the grassroots level with the blessing of the political rulers.

“The official police are either neutralised or an accomplice.”

Although media were present at the book launch, people were asked by Banerjee not to record the question and answer session so the author could have a free and open discussion with the students. Seriously or otherwise, it was suggested that the book, published in the UK by Hurst, might not be available in India until May.

In his introductory remarks to the students, Jaffrelot said: “This book has a story. All books have a story. But this one has two prefaces. It has two prefaces because the first was written in 2013 when the book was ready. And the second had to be written in 2023, 10 years later. Why? Well, this book was ready in late 2013, to be published just before the 2014 elections.”

However, the publishers as well as legal advisers expressed their reservation that there was a high risk “some passages ‘may be deemed as hurtful towards the people of Gujarat, containing an unyielding view of Narendra Modi’. I was asked to cut so many passages that I preferred not to publish the book at that time.”

He went on: “In the meantime, I co-authored other books, including one on the emergency (India’s First Dictatorship: The Emergency, 1975–1977) with Pratinav Anil. And I did another book on what is India after he became prime minister (Modi’s India: Hindu Nationalism and the Rise of Ethnic Democracy). These two books influenced the way I revisited this manuscript.”

He explained the rationale behind his latest book: “History will be the rewritten to such an extent that if it is not in print somewhere, nobody will have any idea of what happened in Gujarat 20 years ago.”

Supporters of Modi point out that India’s Supreme Court upheld a ruling that cleared the then chief minister of complicity in the 2002 Gujarat riots which followed the burning in Godhra of Hindu pilgrims returning from Ayodhya in the Sabarmati Express. Jaffrelot repeatedly used “pogrom” to describe what happened.

He said: “What the book is about, because it has been somewhat rewritten 10 years after the first draft – (it is) doing a different job. The key argument has somewhat changed. It is about the rise of Narendra Modi in Gujarat and the ways and means he used for retaining power for so long.

“You have to demonstrate that everything we see today was there before.

“And Gujarat was the laboratory of today’s India. This is the subtitle of the book that was not there, of course, in 2013, because it was a different story.

“The fact that communal riots were a recipe for electoral success for the BJP [Bharatiya Janata Party] was, of course, something we knew. But that has been demonstrated in an amazing way.

“What we saw in Gujarat was a deinstitutionalisation of the rule of law. It started with the police. When you have something like what happened in February, March, April 2002, in Gujarat, the policemen who had done their job have to be sidelined.

“Those who have been complicit have to be promoted… It’s largely true of the judiciary as well.

“The second point I want to make is the making of a deeper state, the state that goes into society, a continuum between the government and police (and) vigilantes and they report to the same source of authority. That’s something we see today. Press surveillance. The kind of surveillance we see today was invented by (minister of home affairs) Amit Shah in Gujarat 20 years before. So many phones have been tapped, so many people have been surveilled.”

He also spoke of “today’s crony capitalism” and “it’s in Gujarat that you see this nexus between the BJP government and rising stars of Indian capitalism.

“The man who embodies this is, of course, Gautam Adani”.

Jaffrelot said: “For the first time in the history of India, a model of governance invented at the state level can be scaled up to the national dimensions. That’s unprecedented. And that’s what the book is about. That’s why it is an academic book because you have to demonstrate this with figures, with data.

“Whether this is sustainable, beyond the lifetime of the man who invented this, of course, remains to be seen.

“But clearly there is a very neat transformation with continuity in the transformation of a state first, nation second.”

He said he had provided 130 pages of footnotes so readers can crosscheck his sources.

Gujarat Under Modi: Laboratory of Today’s India by Christophe Jaffrelot is published by Hurst, £30.