By Amit Roy

JASWANT SINGH, who died on September 27, aged 82, was a founder of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and served variously as India’s finance, external affairs and defence minister.

But most obituaries recalled he was expelled from the BJP for writing a book that was sympathetic to Muhammad Ali Jinnah.

The character of Jinnah has always fascinated me. As a young barrister who had trained in London, Jinnah was hailed by Gopal Krishna Gokhale, the political and social reformer, as “the best ambassador of Hindu-Muslim unity”.

Yet, Jinnah was the one whose demand for a homeland for Muslims led to the partition of India and the creation of Pakistan.

When Jaswant came to London in January 2010 to promote his controversial book, Jinnah: India-Partition-Independence, I went to interview him. His eagle eyes immediately spotted my guilty secret.

“That’s a pirated edition,” he said.

Indeed, I had picked it up for `300 (about £3) from a pavement seller in Park Street in Kolkata just outside the Oxford Bookstore where it was priced at `1,395 (£14.72).

I then attended the press conference he gave in a committee room in the House of Commons, where there were as many eager Pakistani journalists as there were Indian.

The former called him “an ambassador of peace”, a compliment Jaswant acknowledged with modesty: “I am a soldier in the campaign for expanding the constituency of peace.”

Jaswant was even-handed for he observed: “We were wrong to treat Jinnah as a demon in India, just as I think Pakistan is wrong to treat Gandhi as a demon.”

He summed up nearly 700 pages on Jinnah in one sound bite: “He was a very straight man. At times he was exasperating in his determination and his fixed points. His transition from being an ambassador of Hindu-Muslim unity to the Quaid-e-Azam of Pakistan is an account of barely 1917 to 1947 – (in) 30 years this transition took place.

“He remains an ambassador of Hindu-Muslim unity until he realises he can now no longer achieve what he has to achieve if he continues to pursue the policy of Hindu- Muslim unity. So he changes.

“Is that a good or a bad thing for a politician? Why did he change? He created Pakistan, not the Pakistan of his dreams, what he himself called a ‘moth-eaten Pakistan’, as a compromise. He wanted a place for the Muslims of undivided India so that they could be arbiters of their own social, economic and political destiny. He wanted 30 per cent of the seats in the central legislature and was ready to come down to 20 per cent in the final days.

“I don’t think he really wanted a separate Pakistan because that is perhaps why he was never able to define Pakistan. The thesis that Muslims are a separate nation is not a sustainable thesis.”

India is now big enough – and strong enough – to tolerate and, indeed, welcome views that contradict conventional wisdom.

Manmohan Singh; the then prime minister of India walks in procession through Cambridge University in October 2006 before receiving an honorary Doctor of Law degree

Manmohan Singh; the then prime minister of India walks in procession through Cambridge University in October 2006 before receiving an honorary Doctor of Law degree With US president Barack Obama, first lady Michelle Obama, and his wife Gursharan Kaur at the White House in November 2009

With US president Barack Obama, first lady Michelle Obama, and his wife Gursharan Kaur at the White House in November 2009 With Pakistan prime minister Syed Yusuf Raza Gilani at the 2011 ICC World Cup semifinal in Mohali, north India

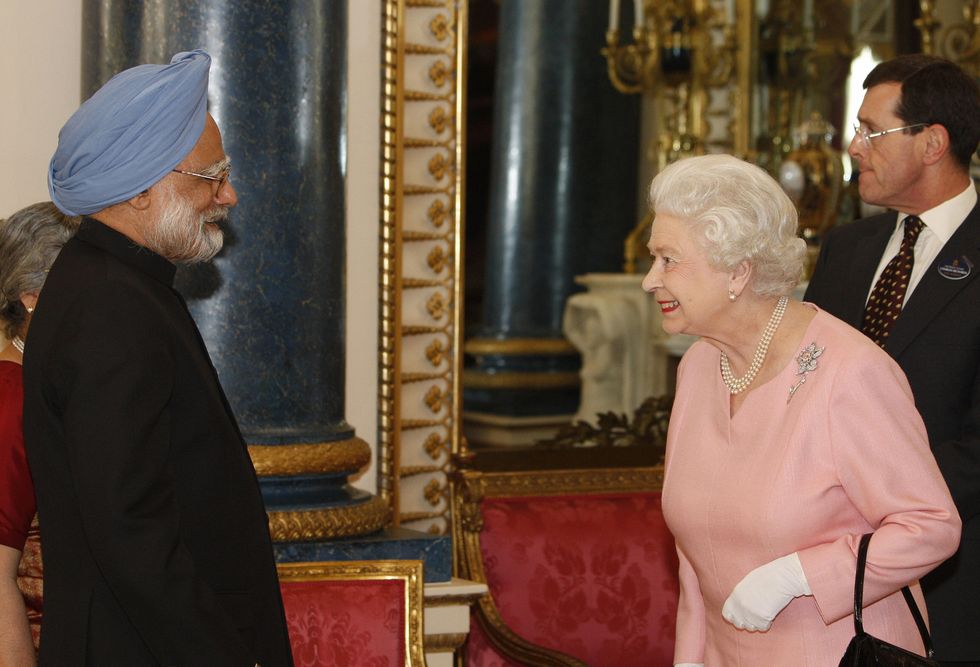

With Pakistan prime minister Syed Yusuf Raza Gilani at the 2011 ICC World Cup semifinal in Mohali, north India Meeting Queen Elizabeth II during a reception for G20 leaders at Buckingham Palace in April 2009

Meeting Queen Elizabeth II during a reception for G20 leaders at Buckingham Palace in April 2009