IT WOULD be ironic if Sajid Javid, who is back from the political wilderness as Matt Hancock’s replacement as health secretary, and Rishi Sunak, who succeeded him 16 months ago as chancellor, fight it out one day for the top job in British politics.

Asian vs Asian for the post of prime minister. That would indeed be progress. Early editions of last Sunday’s (27) papers tipped Michael Gove, Oliver Dowden and Nadeem Zahawi as front-runners for the post of new health secretary.

Javid was mentioned in the Sunday Times only as an “outsider”. Dominic Cummings, who is not Javid’s greatest fan, suggested that Boris’s wife, Carrie, had persuaded her husband to bring him back into government.

Carrie and Javid are apparently friends from the time she served as one of his special advisers when he was communities secretary.

More than willing to do a bit of mischief, Cummings tweeted: “So Carrie appoints Saj! NB If I hadn’t tricked PM into firing Saj, we’d have had a HMT with useless SoS/spads, no furlough scheme, total chaos instead of JOINT 10/11 team which was a big success. Saj = bog standard = chasing headlines + failing = awful for NHS. Need RegimeChange.”

A former investment banker, Javid has served in a number of top jobs. The first time I interviewed him was when he was culture secretary. He displayed a portrait of Margaret Thatcher behind his desk.

David Cameron promoted him to business secretary after the 2015 general election and during the 2016 EU referendum, he was against Brexit.

Under Theresa May, he became the first Asian to be appointed home secretary when Amber Rudd resigned over the Windrush scandal. There was a big party for him hosted by Rami Ranger and Zameer Choudrey, chairman of Conservative Friends of India and Pakistan respectively. Both were subsequently given peerages.

When May stood down, Javid threw his hat into the ring. He secured a promise from other leadership candidates that there would be an inquiry into Tory Islamophobia if any of them won.

Boris made him chancellor, but in February 2020, he showed character by resigning from the post rather than accept a condition from Cummings that the chancellor could not appoint his own special advisers.

One subject in which Javid had previously expressed little interest is health. But on being appointed health secretary, he tweeted: “Honoured to have been asked to serve as secretary of state for health and social care at this critical time. I look forward to contributing to our fight against the pandemic, and serving my country from the cabinet once again.”

The job could be a poisoned chalice since the pandemic is far from over. But perhaps the worst is behind us, thanks to the vaccination roll-out.

If Javid is seen to do well – and he will now be at the centre of British politics – who knows what the future might bring.

A brief history of British sex scandals

THERE was a time when I used to bump into Matt Hancock at Indian functions. At one party hosted by the Confederation of Indian Industry at Central Hall, Westminster, we had a chat about his love of cricket. I have a photograph of him, flanked by MS Dhoni and Virat Kohli, from 2014 when India’s high commissioner at the time, Ranjan Mathai, hosted a garden party for the touring Indian cricket team.

However, Hancock will now merit an honourable mention in the history of political sex scandals in Britain. As the first one to be caught out by CCTV – and inside his own office, too – he will be remembered by future historians more for the manner of his departure than anything he did as health secretary.

Hancock, his wife, Martha Millar, and his aide, Gina Coladangelo, all in their early 40s, are friends from their Oxford days. It is not a surprise that politicians who work long hours away from home get involved with work colleagues. It has always been thus. It is a shame young children are involved. Had it not been for the pandemic, Hancock’s apparent switch of partners would have remained essentially a private affair.

Older readers will be aware that Britain has a long tradition of sex scandals. This is partly because the media tends to be prurient even in sexually liberated times. On balance, the Tories tend to offer a better class of sex scandal. Perhaps the best known is the “Profumo affair” of 1961 which helped bring down Harold Macmillan’s Conservative government in the 1963 general election.

John Profumo, the patrician minister for war in Macmillan’s government, told parliament that he had not slept with Christine Keeler, a pretty 19-year-old girl from a working-class background.

The problem was that Christine was also linked to a Soviet embassy attaché. Profumo resigned after admitting he had not told the truth.

Christine had swum naked in a swimming pool in a country mansion where guests had included Pakistan’s military ruler, Field Marshal Ayub Khan. Profumo quit politics and devoted the rest of his life to charitable work, and his marriage to the actress Valerie Hobson also endured.

It was poor Christine who was punished – and unfairly so. The affair inspired books, movies and plays.

Back in 1983, Cecil Parkinson, whom Margaret Thatcher was grooming as her successor, resigned as secretary of state for trade and industry, after having a daughter, Flora, with his secretary, Sara Keays. He never acknowledged the child.

In 2002, Edwina Currie, a former Tory minister, published a “kiss and tell” account of a four-year affair with John Major in the 1980s. He was no longer seen as “the grey man” of British politics and succeeded Thatcher as prime minister.

In 1985, the Liberal party leader, Paddy Ashdown, who admitted to an affair with his secretary, Tricia Howard, earned the nickname “Paddy Pantsdown”.

Treading the boards again

IT IS good to be able to report that life is returning to Britain’s theatres, closed for over a year.

Last week, I discovered the toilets had become gender neutral at the Lyric Hammersmith, which might prove too progressive a step for British Asians.

I enjoyed Tanika Gupta’s The Overseas Student, imagining Gandhi’s years in London between 18 and 21. On the sea voyage from Bombay to Tilbury, Gandhi is told by a steward to move from the deck reserved for Europeans.

He reflects: “The English are so exquisitely polite. No shouting or cursing – simply a civil tone and firm kindness. It is a joy to be reprimanded by them.”

I was also at the National Theatre which has reopened with Dylan Thomas’s Under

Milk Wood, directed by Lyndsey Turner. On both occasions, two or three seats were left vacant on either side of mine.

Diversity on Love Island

I’M EVEN less of an authority on Love Island than I am on most other things. In fact, I don’t think I have ever watched an episode of the reality TV show in which good-looking young men and women are isolated on an island and encouraged to pair up in the search for “romance” until a couple emerge as the winners.

I note, though, that Shannon Singh, 22, daughter of a Punjabi father and a Scottish mother and described as “a former glamour model, social media influencer and DJ”, appears to be the first Indian origin contestant on Love Island.

Now, that, too, is progress. I hope Shannon wins. She pretends to be a lot naughtier than she probably is. Her talk of how liberated she is has got the tabloids frothing at the mouth. She was uninhibited when appearing on the BBC Asian Network programme, Brown Girls Do It Too. Incidentally, both plays received excellent reviews.

The Calcutta Club

The Calcutta Club The Bengal Club lawns

The Bengal Club lawns

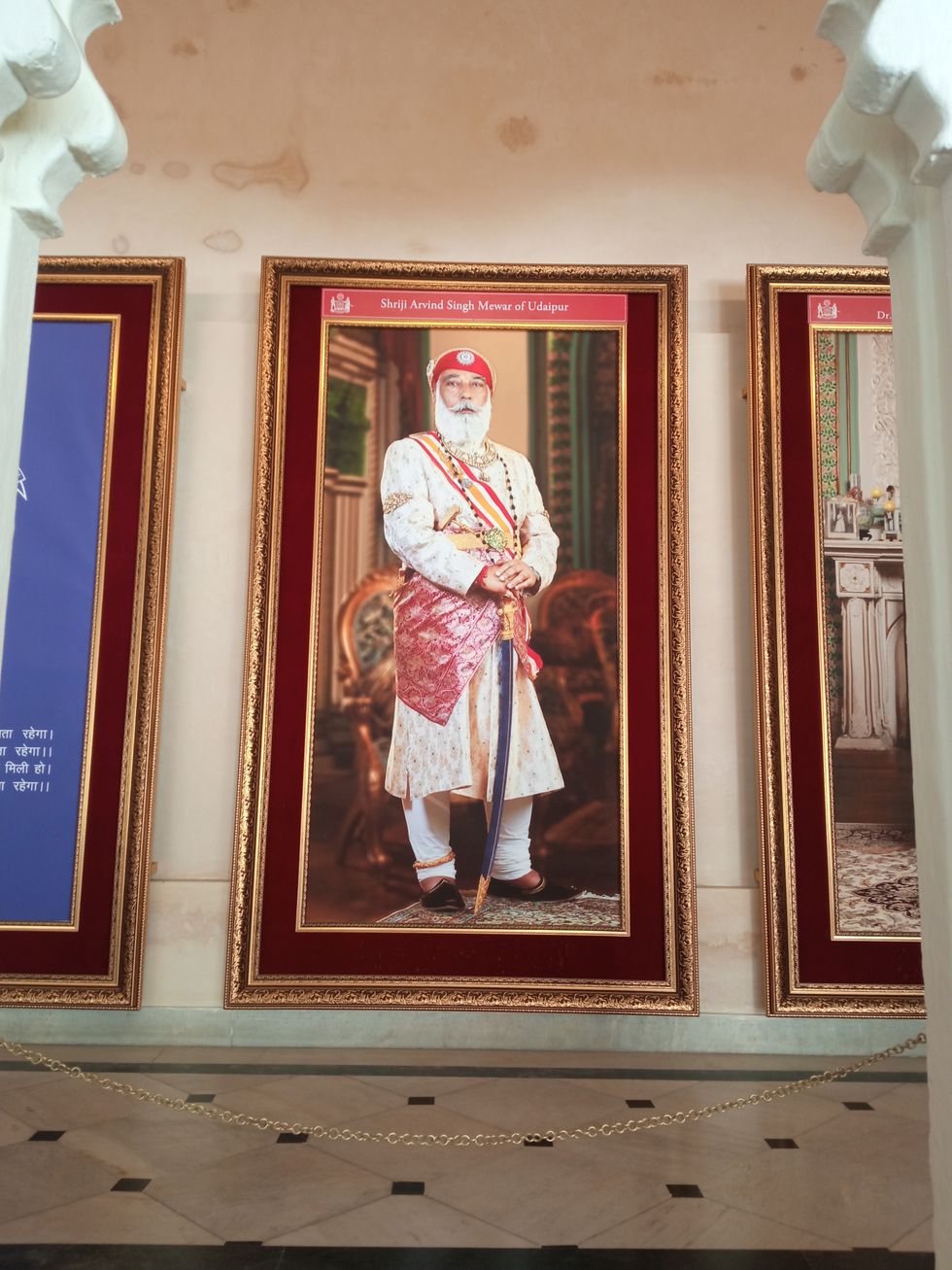

His portrait in the City Palace

His portrait in the City Palace

Pakistani artist Moazzam Ali Khan caught the attention of Bollywood legend Javed Akhtar with his soulful YouTube cover of Yeh Nain Deray Deray

Pakistani artist Moazzam Ali Khan caught the attention of Bollywood legend Javed Akhtar with his soulful YouTube cover of Yeh Nain Deray Deray John Abraham to headline action thriller Tehran

Getty Images for DIFF

John Abraham to headline action thriller Tehran

Getty Images for DIFF

Tikri Border, Haryana-Delhi by Aban Raza

Tikri Border, Haryana-Delhi by Aban Raza Harmz Matharu

Harmz Matharu Abhishek Bachchan in Be Happy

Abhishek Bachchan in Be Happy Devika's soulful vocals shine in her new Punjabi ballad Wisteria

Devika's soulful vocals shine in her new Punjabi ballad Wisteria Indian Idol star Nitin Kumar promises a soulful mix of qawwali, Sufi, and folk music at his upcoming UK performance

Indian Idol star Nitin Kumar promises a soulful mix of qawwali, Sufi, and folk music at his upcoming UK performance Kunal Kamra during his show

Wikipedia

Kunal Kamra during his show

Wikipedia

Swiss-Indian singer BombayMami is making waves with her bold style and sound

Swiss-Indian singer BombayMami is making waves with her bold style and sound Hania Aamir receives a questionable honour in London

Hania Aamir receives a questionable honour in London

A resident in Odessa, Ukraine, as smoke rises from a fire following a strike earlier this month amid the Russian invasion

A resident in Odessa, Ukraine, as smoke rises from a fire following a strike earlier this month amid the Russian invasion