WARM tributes have been paid to the hotelier Joginder Sanger, long-time chairman and vice chairman of the Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, who died last Friday (28), aged 82.

The previous Saturday (22), Sanger and his son, Girish, had attended celebrations to mark Lord Swraj Paul’s 94th birthday at the Indian Gymkhana Club in west London.“He was a close friend for a long time – and a lovely human being,” Lord Paul told Eastern Eye.

With Sanger’s death, another prominent member of the first generation of Indian immigrants to the UK passes away, taking with them first-hand experiences of what life was like in the 1950s and 1960s.

Sanger would often pay tribute to prominent Indians as they passed away. Now, it is the turn of others to remember him. Sanger served as vice chairman of the Bhavan from 1993-2011, and as chairman from 2011-2022.

“Joginderji was a very simple yet profound human being,” Dr MN Nandakumara, executive director of the Bhavan, summed up for Eastern Eye. “He wanted our culture and heritage to be easily available to our younger generation.”

The Bhavan also issued a statement: “He was the one who started the Bhavan’s annual Diwali banquet, which has been going on for over 35 years now. During his term as the Bhavan’s vice chairman and chairman, the Bhavan reached new heights in the field of our art and culture. He sincerely believed that we should make our cultural education easily accessible to our children, who are the future of our cultural movement.”

Sanger’s businesses, especially his hotels – the Washington in Mayfair, the Bentley in Kensington, and the Courthouse hotels in Soho and Shoreditch – have been managed for some time by his daughter, Reema, and son Girish.

Surviving members of his family include his wife, Sunita – the couple were married in 1971 – and Girish’s two sons and a daughter.

The Asian Who’s Who, which used to be published annually by Jasbir Singh Sachar, named Sanger “Asian of the Year” in 2011.

His entry, accompanied by a photograph of a youthful Sanger, says he was born in “Chack No 258, Lyallpur” on June 6, 1942. He settled in Apra, a tehsil in Jalandhar, Punjab state, where he received an education from DAV College, before arriving in Britain in 1961.

He “became a member and supporter of various religious, social, welfare and sports organisations”.

As a travel agent, he worked for many years from an office in Poland Street in the West End of London.

His Courthouse Hotel in Soho is so called because it contains an actual magistrates’ court with adjoining cells, where his guests like to sit sipping a cocktail. The court itself was converted into a cinema, where many Bollywood premieres have been held. Quite often, the Indian Journalists’ Association would use the Courthouse for one of its functions, when he would be happy to take personal charge of the menu.

When Dev Anand, died at the Washington in 2011, there was a memorial service at the hotel for the Bollywood legend. Sanger read out a note he had received from the actors’ union: “Equity UK is saddened to learn of the sudden passing away of Mr Dev Anand during his visit to London. We appreciate his lifelong contributions to the Indian film industry and send our heartfelt condolences to his family.”

Guests at the Bentley included Indian dignitaries, among them president Pratibha Patil and prime minister Dr Manmohan Singh.

Actress Liz Hurley had no option but to announce the end of her marriage to Arun Nayar after the now defunct News of the World broke the story of her assignation at the Bentley with Australian cricketer Shane Warne. Sanger was abroad at the time and felt rather embarrassed that the couple had almost gone out of their way to advertise their affair.

But Sanger was not entirely displeased about the free publicity.

When Indian journalists met Imran Khan, then an opposition politician in Pakistan, during a visit to London, they picked the Bentley for the meeting.

Sanger was in reflective mood as he stepped down in 2022 after 40 years of service to the Bhavan.

“To me, the Bhavan became more important than my own business,” he told Eastern Eye.

It is generally recognised that he put the finances of the Bhavan, once precarious, on a sound footing. Sanger was 19 when he came to Britain, initially to study engineering. He recalled how the perception of India had changed over the decades, and that an organisation such as the Bhavan was needed to “prevent young Indian boys and girls from going astray”.

On a trip to Rotterdam in 1964, he got into a conversation with a Dutchman with limited fluency in English.

“He asked me, ‘Where are you from?’ I said India. He did not know anything about India. They have a different word in the Dutch language for India. When I explained about India to him, he said in his limited English, this was where ‘people starved to death’. That was India’s reputation among ordinary members of the public in Europe.”

In the decades since, there had been a transformation in how people thought about India, said Sanger. “And today, I feel so proud of India. Today, we are among the three or four top economies of the world. Some of our politicians (in India) have been good, others bad. But they have raised India to this level. One of my principles is that mistakes are made by people who try to work and do something. But a person who doesn’t work, what mistake will he make?”

Sanger hailed the contribution of Indians across the globe: “Not only in England, but in America, in fact, everywhere, they are the backbone of society.”

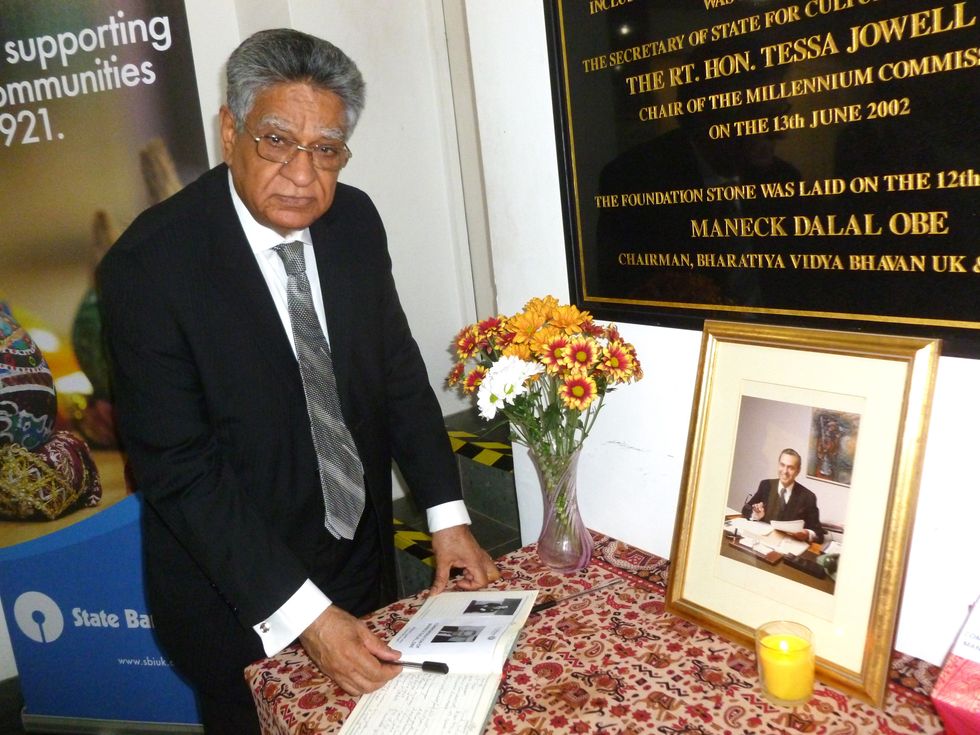

Back in 1980, when Sanger was working as a general sales agent for Air India, he received an urgent summons one day from the late Maneck Dalal, a Parsi and then the highly regarded regional director of India’s national carrier.

Sanger rushed to the meeting with Dalal thinking something had gone wrong with a flight. Instead, he discovered Dalal had been dealing with Mathoor Krishnamurthy, the then executive director of the Bhavan.

The latter, who was in a despondent mood, was flying to India to talk about the problems of the Bhavan with the organisation’s leaders in the country.

Sanger admitted modestly: “I had come from a village. I had never heard of the Bhavan. At first, I thought it had something to do with religion, but it was my ignorance. I was wrong. I realised this institution is important for future generations of our children.”

With the first generation of immigrants, husbands and wives went out to work, often leaving children unsupervised after school.

“There was a risk they would become teddy boys.”

At Dalal’s request, Sanger took up the task of helping the Bhavan, initially financially. The Bhavan had been given a donation of £256,000 from the Birlas, one of India’s premier business dynasties, with the stipulation that only the interest from the capital could be used as expenditure. Sanger used his contacts with the Bank of Baroda and offered to use his own bank accounts as collateral to steady the finances of the Bhavan. His intervention paid rich dividends.

When people would not pay £250 to book a table of 10 for a Bhavan dinner, he reduced the cost to £100. He felt “promoting Indian culture is a must”.

By and by, the Bhavan built up a healthy bank balance and was able to expand. With passing years, Sanger’s commitment to the Bhavan grew. In 2017, he appealed to the Bhavan’s executive director, Dr Nandakumara, and members of the governing committee, to find his successor as chairman “while I am still in good health. But they wouldn’t let me go.”

He was finally allowed to step down in 2022. Sanger explained he had a very Indian view of charitable work: “If you put £5 into good work, god gives you £50. My business success is not because of my wisdom, but god’s kindness.”

Inside the Kerala actress assault case and the reckoning it triggered in Malayalam cinema AI Generated

Inside the Kerala actress assault case and the reckoning it triggered in Malayalam cinema AI Generated

Actor-producer Dileep was arrested on 10 JulyYoutube Screengrab/Kerala Kaumudi

Actor-producer Dileep was arrested on 10 JulyYoutube Screengrab/Kerala Kaumudi Members of the Women in Cinema Collective (WCC) meeting with the Chief Minister of KeralaInstagram/

Members of the Women in Cinema Collective (WCC) meeting with the Chief Minister of KeralaInstagram/ Actor Dileep and whistleblower Balachandra Kumar, whose testimony and disclosures played a crucial role in advancing the investigation Youtube Screengrab/Kerala Kaumudi

Actor Dileep and whistleblower Balachandra Kumar, whose testimony and disclosures played a crucial role in advancing the investigation Youtube Screengrab/Kerala Kaumudi Dileep coming out of the court after the verdict Instagram/

Dileep coming out of the court after the verdict Instagram/ Advocates T. B. Mini and Aja Kumar, representing the survivor in the Kerala actress assault caseYoutube Screengrabs/ Oneindia Malayalam

Advocates T. B. Mini and Aja Kumar, representing the survivor in the Kerala actress assault caseYoutube Screengrabs/ Oneindia Malayalam Four of the six convicted accused in the Kerala actress assault case Youtube Screengrabs/ 24 News

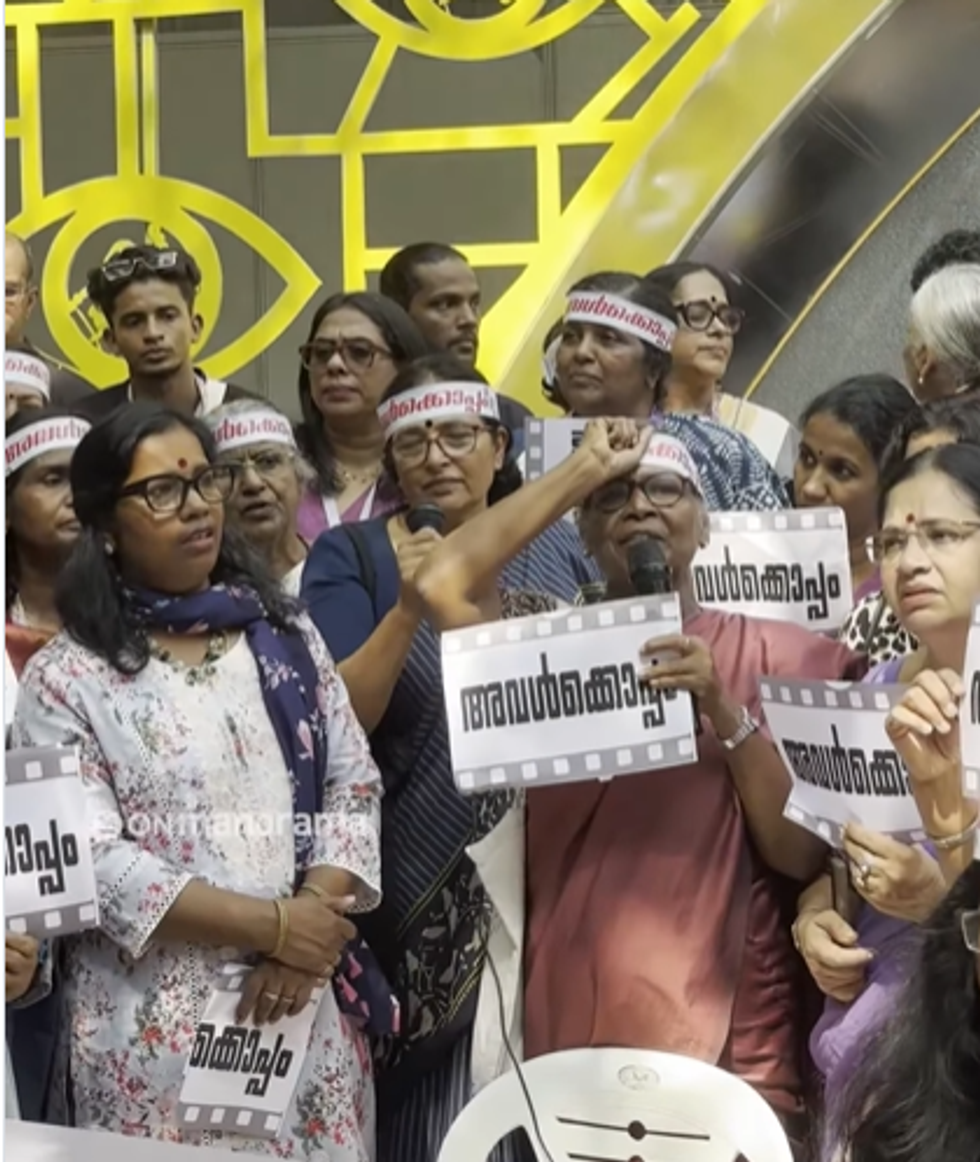

Four of the six convicted accused in the Kerala actress assault case Youtube Screengrabs/ 24 News  Film personalities and activists gather at the Tagore Theatre to reject the court\u2019s decision and demand systemic change for women\u2019s safety Instagram Screengrab/onmanorama

Film personalities and activists gather at the Tagore Theatre to reject the court\u2019s decision and demand systemic change for women\u2019s safety Instagram Screengrab/onmanorama  How one survivor’s fight shook an entire industryAI Generated

How one survivor’s fight shook an entire industryAI Generated