Government must be tough on violent disorder, but prime minister Sir Keir Starmer’s challenge now is to set out what it means to be tough on the causes of disorder too.

Starmer needed no reminder that the first duty of government is to keep the peace. His experience of the 2011 riots, as director of public prosecutions, informed the focus on robust policing, rapid prosecutions and visible sentences to prove the forces of law had taken back control of the streets.

But bringing criminals to justice is not Starmer’s main job anymore. A prime minister has a broader responsibility than a lead prosecutor. His next challenge as a national leader is to help the public to make sense of such troubling events, so as to underpin a roadmap for the longer-term response. What would not meet this moment would be for the government, as it too easily could, to lapse into parallel messages to different audiences – reassuring a white majority group that legitimate concerns about immigration are recognised, with a side-message to reassure ethnic minorities that community spaces will be protected from the threat of racist violence.

There were terrifying scenes in the attempts to burn down hotels containing asylum seekers and attack local mosques. As historian David Olusoga notes, attacks on asylum seekers, mosques and ethnic minorities amounted to the most concerted effort at organised racist violence for decades, bringing into the 21st century a spectre of racist violence that ethnic minority Britons had hoped would never return.

Sporadic outbreaks of disorder across 30 locations showed the contagious risks of flashmob violence. It is striking how few people it took to spread such widespread mayhem and fear. The four or five thousand people who took part in violent disorder nationwide would not fill even the smallest football league ground. Yet the moral oxygen comes from a broader group. Thousands of people shared Telegram posts hoping to turn violent fantasies in a self-fulfilling prophecy. Up to one in ten people were sympathetic to the disorder.

The two per cent who tell YouGov they strongly support the disorder adds up to a radicalised rump of one to two million people whose fear or hatred of change makes them believe that violence is now legitimate and necessary. Most of those who support the violence imagine they live in a country where most other people did so too, a striking indicator of how far those with radicalised and extreme views have come to inhabit a parallel universe.

Some simple, unifying foundations can be found to speak to the vast majority, across different groups and political views. This is not who we are – or who we want to be.

National and local leaders should elevate the voices of those who turned up to clean up. Beyond symbolic acts of local and national recognition, in future honours lists, for example, that could involve substantive efforts to work out how to capture that voluntary energy to shape the conversation about what happens next.

Tackling underlying causes is more contested territory. Did violence bubble up because politicians were too afraid to debate immigration, or were they stoked up by the incendiary language of those who talk about little else? Is the call for change in left-behind towns about immigration and demographic change – or primarily about opportunity, jobs and housing?

The prime minister has been told he should slash immigration and leave the European Convention on Human Rights; crack down on social media misinformation; recognise the scale of anti-migrant and anti-Muslim prejudice; regenerate the northern towns; and restore trust in politics. Many people respond to any major event by calling for what they already wanted. This disorder will entrench Starmer’s own instincts about his chosen priorities for government – including economic growth, better public services and reducing violent crime. It should challenge him too to articulate more clearly a broader story about the foundations of a decade of national renewal.

Only by speaking to the whole country at once can the government articulate a democratic argument about how we talk about those much-discussed “legitimate concerns” too. The phrase may have become a political cliché, yet unpacking the principles underlying it is crucial to ensuring we have the democratic debate about immigration policy and integration that gives no space to racism, threats and violence.

Understood properly, legitimate concerns are a two-way street. Net migration is likely to halve in the next 12 months – but it would be naïve to think that would make any difference to those chanting Tommy Robinson’s name and obscenities about Allah outside the local mosque.

The government should provide more visible space for democratic debate about future choices on immigration and integration policy, not because of the disorder, but because it was right to do so anyway.

Tackling the causes of violent disorder requires a stronger effort to unpack the causes of fear, hatred and prejudice to underpin a sustained effort to tackle it.

(Sunder Katwala is director of the thinktank British Future and author of ‘How to be a patriot’.)

Shashi Tharoor

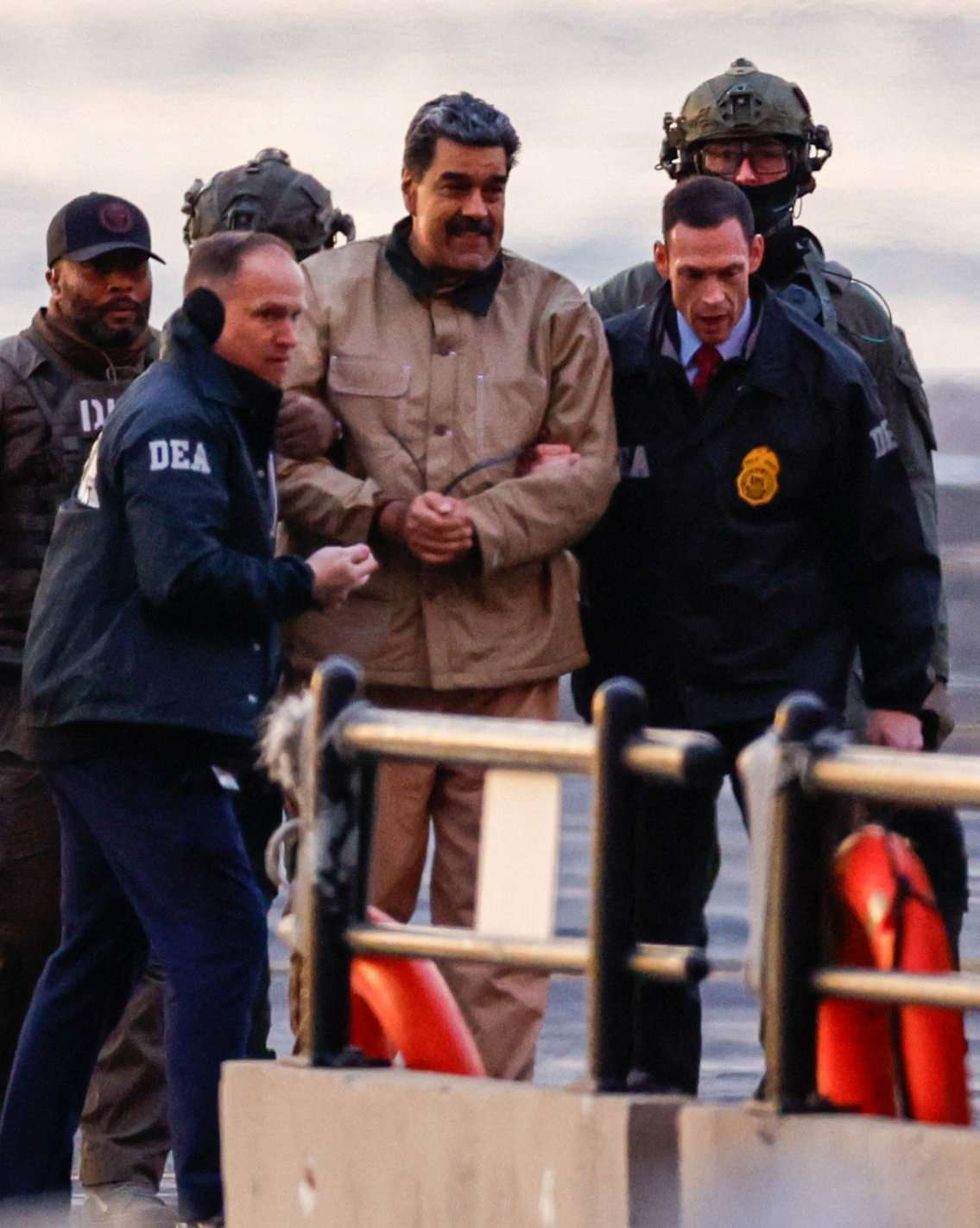

Shashi Tharoor Nicolás Maduro arriving at the Down town Manhattan Heliport.

Nicolás Maduro arriving at the Down town Manhattan Heliport.