Laughter is the best medicine, as the old saying goes, and this certainly appeared to be the case with the author Moni Mohsin, whose session was one of the hits of the recently held Khushwant Singh Lit Fest (KSLF) in London.

Mohsin, who created a character called “the Social Butterfly”, an upper middle-class woman in Lahore, was asked what her creation would make of Rishi Sunak, an Indian, becoming the British prime minister.

The Social Butterfly would be delighted, said Mohsin, a Pakistani-origin columnist and comedy writer who lives in London.

“Mashallah, mashallah, mashallah, he’s not from the poors,” the Social Butterfly would say. “Unlike other people who have come from the migrants, who have had to work hard and lift themselves, but he is mashallah not from the poors.”

The Social Butterfly – famed for her malapropisms – has a husband, Jannu, who likes books as he has been to Oxford. His wife proudly proclaims he is an “Oxen”.

Commenting on the claim that “Amitabh Bachchan and Aishwarya Bachchan” had invested in a company called “Offshore” in the Panama, she is scornful that her husband failed to have the foresight shown by the stars from Bollywood.

“Obviously, Jannu, my husband, being the loser that he is, hasn’t (invested).”

Mohsin told Eastern Eye, who are media partners with KSLF, that the Social Butterfly had a following in India, and laughter brought Indians and Pakistanis together.

She explained: “The social structure is the same. It’s not just in the Punjab, but in all of India and Pakistan – the social structure is the same. So if (as a Pakistani) you meet an Indian in London and ask them, ‘Where do you live?’ and (the reply is) ‘In Delhi,’ you go, ‘You must be knowing so and so.’ That’s because the social elites are so small. It’s the same in both countries. So the Social Butterfly is enjoyed in India, because she is so familiar.”

As for India’s prime minister Narendra Modi, the Social Butterfly is “very impressed because, as she says, ‘his 56-inch chest is bigger than Kim Kardashian, even’. All her Indian friends in London love Modiji. She’s also in love with Modiji because she wants to be invited to their parties.”

She added: “We’ve turned (the) English (language) into our own English – which is entirely justifiable. We love asking each other what our ‘good name’ is.

“And I must give due credit to somebody else who also wrote like this a long time ago – and that was Shoba (now Shobaa) De. She wrote in Stardust magazine which I used to devour in the 1970s… I learned from her as well. I was talking to a friend in Delhi who was having lunch sitting outside in November and he said, ‘Oh, there’s such a nipple in the air.’”

Rahul Singh, who runs KSLF with his partner, Niloufer Bilimora, said he was trying to carry on with his father’s work of trying to bring together the people of India and Pakistan through the medium of books.

This year’s KSLF was held in the Brunei Gallery at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) last month. He said: “One of the great things about holding it in London is you can invite Indian and Pakistani speakers to share the platform.”

For example, Reham Khan, whose brief marriage to the former Pakistani prime minister Imran Khan ended in acrimony, flew over from America where she now lives to take part in the KSLF (she steered clear of discussing her personal life).

The theme of the event this year was ‘Connecting Futures’. Speakers included Lord Meghnad Desai who discussed how “economics has abandoned the poor” with Vicky Pryce. Lord Karan Bilimoria, who is now vice-president of the Confederation of British Industry (CBI) after having served a year as its president, and Lalita Taylor talked about ‘the UK and India: Cheers to a Future Perfect?’

After the poets Imtiaz Dharker and Ruth Padel had launched the festival with a session called ‘We are all from somewhere else’, Oxford don Nandini Das talked about her book, Courting India: England, Mughal India and the Origins of Empire with fellow historian Roddy Matthews.

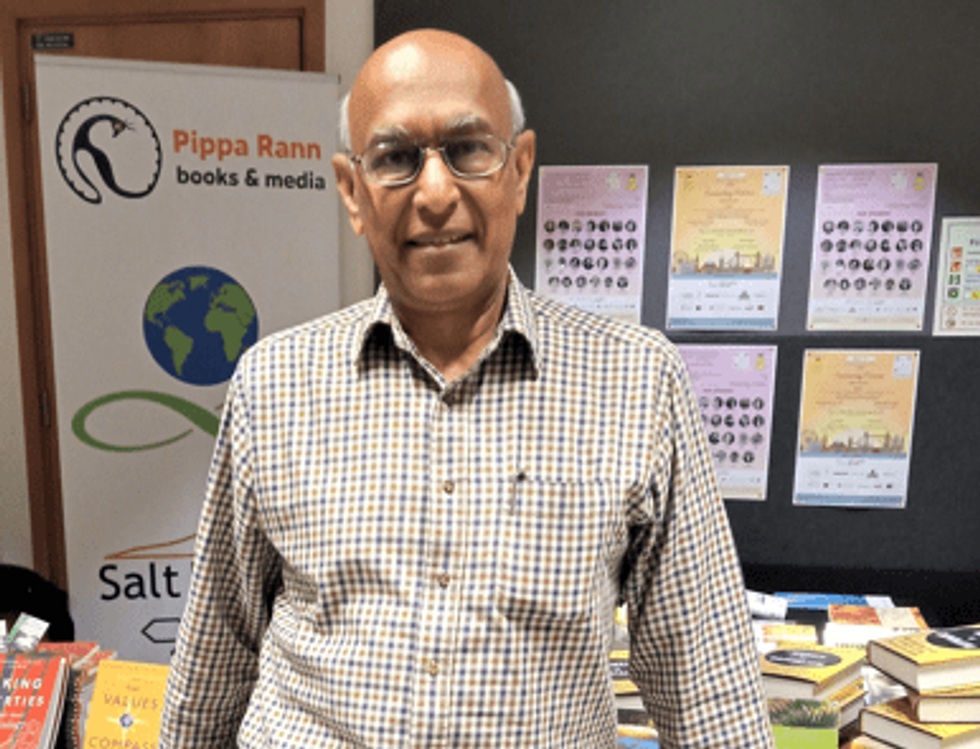

Two publishers attended the event. One was Prabhu Guptara has a niche publishing house, Pippa Rann Books & Media, which has brought out Ram Gidoomal’s memoir, My Silk Road: The Adventures & Struggles of a British Asian Refugee.

The festival was compered by the academic Rachel Dwyer, whose husband, Michael Dwyer, was also present. He runs Hurst Publishers, and its portfolio covers international affairs, the Islamic world, politics and the social sciences. It has brought out such books as Faisal Devji’s Is Race a Red Herring in Rishi Sunak’s Rise?