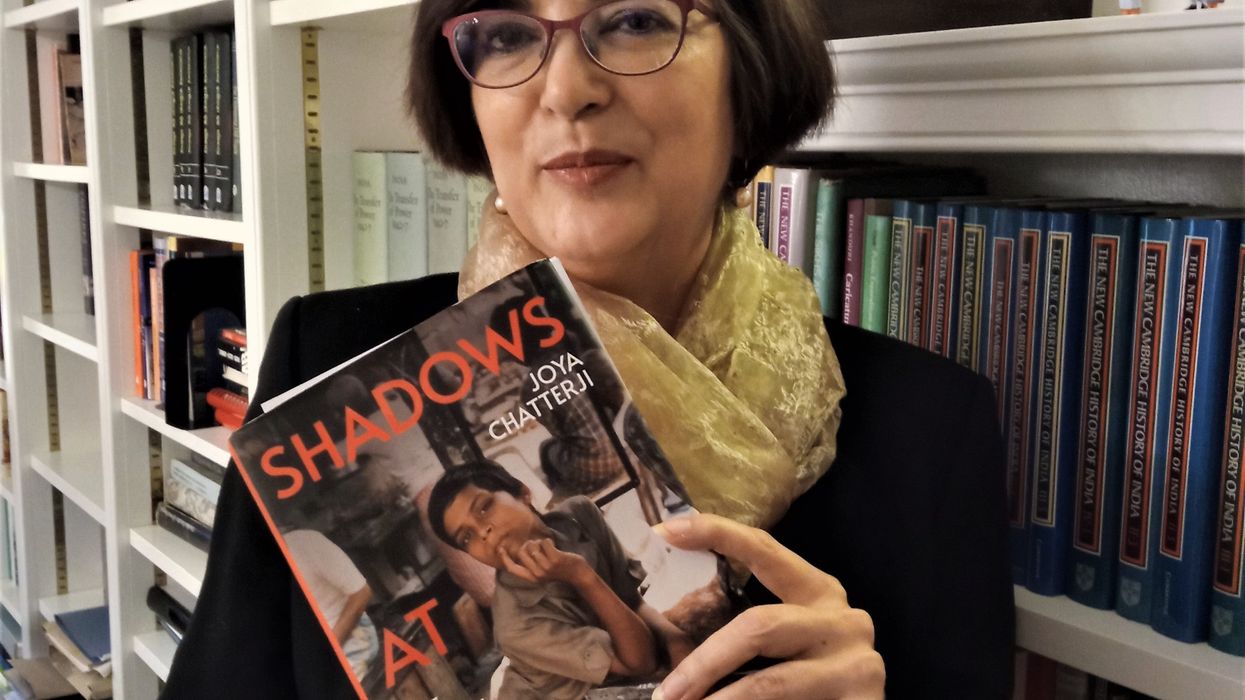

IN PROFESSOR Joya Chatterji’s Shadows at Noon: The South Asian Twentieth Century, which won her the £50,000 Wolfson History Prize earlier this month, there are a couple of sections that will be of particular interest to British Asian readers.

One focuses on the power of Bollywood, where boy meets girl, boy loses girl, boy gets the girl back, and they marry to live happily ever after.

However, as Chatterji highlights, the reality of pursuing love in India across boundaries of class, caste, and religion can be far more dangerous – even fatal.

“Love across caste lines – particularly between ‘touchable’ and ‘untouchable’ castes – remains perilous in the extreme,” writes the Cambridge historian.

“‘Untouchables’ who dare to love ‘touchables’ risk their lives, and they know it.” “Love, then,” declares Chatterji, “continues to be a dangerous business in south Asia.”

She adds: “In her debut novel of 1997, The God of Small Things, Arundhati Roy [who won the Boozer Prize] writes of ‘Love Laws’ that lay down rules about ‘who should be loved, how and how much’. The list is long. One can break them in a host of ways – by transgressing prohibited degrees of kinship, by adultery, by crossing caste, class or religious boundaries, or by loving someone of the same sex or gender. All these forms of love meet severe social sanction, in some cases backed by the courts.”

For example, “the barbaric custodial killing of Ammu’s Paravan Dalit lover, Velutha, in The God of Small Things rings true; the facts of south Asian life often being more brutal than fiction.”

Many of the laws, a hangover from colonial times, have yet to be reformed 77 years after independence.

“In 1923, the Indian Penal Code (Amendment) Act strengthened an act of 1860, so that any man found to have forced a woman under the age of eighteen with the intent of sexual intercourse could be put away for ten years in jail,” writes Chatterji. “The woman herself faced no charges; the state assumed that the eloping girl had no agency of her own and was taken by force, or lured away. This denial of her sexuality and intelligence was convenient for any family that accepted back into its fold a victim and not a sinner, because, otherwise, the family itself would face ostracism.”

On family life, Chatterji says: “Let’s get one thing clear at this point. The new nuclear family was not based on love. These spatial reconfigurations of the household did not mean that pre-marital passion became socially acceptable. Outside a tiny bubble, love was, and still is, regarded as the greatest moral threat to dharma (duty), to honour (izzat), and to the order of things. Love before marriage brings shame upon both households and the lovers themselves. It is understood as lust: a vice.”

She gives detailed examples of some notorious and shocking cases.

“In 2007, Rizwanur Rahman, a thirtytwo-year-old Muslim man from a poor family (in Kolkata) fell in love with a young woman born into a wealthy Marwari Hindu household. He had met Priyanka Todi at the graphics training school where he taught, and where students admired him for his teaching and kindliness. Both were adults. They married secretly under the Special Marriages Act. Priyanka moved to Rizwanur’s paternal home in a working-class neighbourhood. Priyanka’s family called in the police to force her to return to her parental home. She did this under duress. Soon afterwards, Rizwanur was found dead by the railway tracks. The police claimed that he committed suicide. Others believe that he had died after being tortured in police custody.”

The author has also written about sexual violence against women, all too common in India.

The Delhi gang rape “is known to Indians”, she says, “but not to all in the worlds beyond it. On a freezing December night in 2012, a 23-year-old woman intern in physiotherapy was returning home with a male friend after an evening at the cinema. It was not late, about eight o’clock. They waited for a bus in ‘genteel’ South Delhi, in a ‘decent’ neighbourhood in the heart of the nation’s capital. What looked like a private bus picked them up.

“The other passengers, and the ‘driver’, were drunk young men. They gangraped the woman, and when they had had their pleasure, forced an iron rod into her vagina. They beat her friend with the same rod when he tried to fight back. The Indian media named the young woman Nirbhaya (Fearless), because of the courage with which she fought for her life and helped the police identify the perpetrators.

“The pseudonym was a legal necessity: Indian law gives rape victims anonymity to protect them from the stigma that they (rather than the rapists) suffer. Nirbhaya died of her injuries. When women’s movements across India demanded better protection for women in cities at night, senior male politicians dismissed the Delhi activists as ‘dentedpainted’ ladies for wearing jeans and lipstick, questioning their morals and also questioning their right to bring an action to court.

“But something unusual happened next. Nirbhaya’s father announced her true name to the world. She was Jyoti Singh Pandey. Her father, far from being shamed, claimed his raped and battered daughter. He told Jyoti’s story: of her striving to study, of her move to the city to learn more, of her moral example to the children of her village.”

“There are of course exceptions,” concedes Chatterji.

“Couples who have married for love can be found in the great metropolises, among the urban poor as well as the anglicised elites. The cities’ most wretched parents have been known to welcome ‘elopements’ because of the relief they bring from wedding expenses and the dowry. University professors, doctors, lawyers and journalists dwell in a social world of their own in which love is okay. But even here, in this space, crossing certain lines is shocking.”

She gives her own example: “My own first marriage to Prakash, a university lecturer of the same caste but from a poor family, shocked Delhi’s liberal literati. My father (1921-2004) could hardly have been more broad-minded for an Indian man of his generation – but for two years, he refused to speak to me to try and stop the inevitable, although the Coventry to which he banished me broke both our hearts.

“The sticking point in our case was class. Prakash is village-born and was the first person of his clan to go to university. I was from a landed family which for generations had produced doctors and lawyers, not to mention literate women since the early 20th century. My determination to enter this ‘love marriage’ was too much for my father to swallow. (He reconciled himself to the situation in the end, but it took a while.)”

Shadows at Noon: The South Asian Twentieth Century is published by The Bodley Head. (Hardback £30). (Vintage Publishing paperback £14.99)