By Sunder Katwala

Director, British FutureI AM a child of the NHS. Like millions of people in Britain I took my first breath in an NHS hospital; in my case, the Doncaster Royal Infirmary, on a cold April day in 1974.

If it hadn’t been for the National Health Service, I wouldn’t have come to exist at all, since it was the NHS that brought both of my parents to Britain. My father was born in Baroda, Gujarat, a few years before Indian independence. After studying at medical school and working for a summer as a doctor in the Indian railways, he came over to England, in the spring of 1968, to work for the NHS. That was how he met my mother, who grew up in County Cork in Ireland, before taking the ferry to England, to begin her training as nurse. That story of the NHS is the story of Britain too.

If none of us have ever experienced anything like the great public lockdown of 2020, there is one thing that the Covid-19 crisis has confirmed, rather than changed. That is the status of the National Health Service as our most cherished public institution – even as it prepares to face perhaps the greatest pressure in its seven decades serving the public over this coming month when the epidemic may peak.

The NHS has also become a symbol of immigration – providing many people’s strongest positive association with its benefits. This was a striking feature of the National Conversation on Immigration, which researched how people think about immigration, through conversations with the public in 60 towns and cities around the UK. The contribution of doctors and nurses from overseas came up in every single location. Participants drew on their personal experiences in the NHS at many of the moments of greatest anxiety, sadness or joy for their own families.

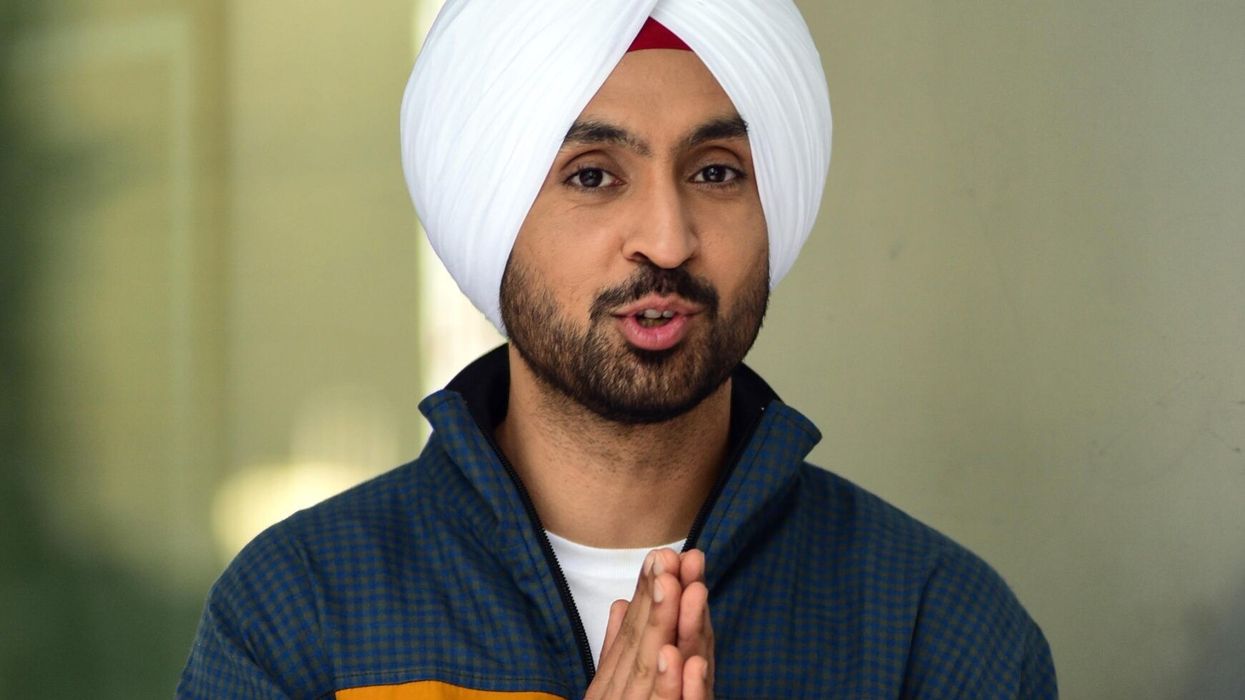

Indian doctors were the first image that came to mind for many people when they spoke of the benefits of immigration. The enormous British Asian contribution to the NHS has now become something of a (largely positive) stereotype. So it was that when Chancellor Rishi Sunak conducted his first budget last month, he found himself portrayed in a Daily Mail front-page cartoon as an Indian doctor. Given that he is the son of a GP and a pharmacist, perhaps it was an appropriate theme to portray him as giving the economy an emergency vaccination of billions of pounds to bring it through the shock of the epidemic. Across the floor of the Commons, Dr Rosena Allin-Khan, proud to be of Pakistani and Polish heritage, has returned to the wards to carry out shifts during the Covid-19 crisis while taking up a Shadow Cabinet role to champion mental health. The Tooting MP’s impressive campaign made her runner-up in the Labour deputy leadership contest last weekend, after fewer than than four years in parliament.

The NHS is more than a symbol of migrant contribution. Perhaps what it captures best is what true integration really means in our multi-ethnic society. So many people who came to this country from overseas – and those of every ethnic and faith background born here too – contribute to something that benefits us all.

That now finds a tragic reflection as the news reveals how doctors, nurses and healthcare assistants have made the ultimate sacrifice through their contribution to our care during this terrible epidemic. Dr Habib Zaidi, aged 76, a GP in Leigh-on-Sea in Essex for a quarter of a century, was among the first to be publicly named as having lost his life to Covid-19. His four children – three doctors and a dentist – spoke of how his sacrifice reflected his sense of vocational service. Sombre daily announcements from NHS Trusts have illuminated the everyday reality of the diversity of contributions, with NHS staff paying tribute to the dedication and now sacrifice of colleagues who came to this country from Pakistan and India, from Sudan and Egypt, from the Philippines, from Ireland and across Britain.

So the National Health Service has already become the focus of our first new national tradition of the Covid-19 crisis. The idea of clapping for our carers at 8pm on Thursdays has so caught the public mood that it is estimated that over 25 million people have taken part. These are probably the UK’s biggest shared public moments of the decade. The spirit of that weekly applause could be given a more formal outlet on this year’s birthday of the NHS on July 5, 2020. That day could now become a day of national thanksgiving for the service that will, hopefully, by then have begun to bring us through the worst of this crisis.

My twin sister now carries on the family tradition in the NHS. “I’m a nurse, what’s your superpower?”, her Facebook profile reads. The importance of the NHS as representing Britain at its best has never been more valued.